Robert Henderson drifted downstream in the shallow waters of the Indian River, heading toward Forty Mile to get supplies for the men panning for gold at Gold Bottom Creek. Realizing that the low water of late summer would jeopardize his flimsy skin boat, he decided to go down the Thron-diuck - the Klondike, as white men pronounced it. Henderson guessed that the Gold Bottom flowed into it. It was a fateful decision, for it led him to encounter George Washington Carmack and his brothers-in-law, Skookum Jim and Tagish Charley, the men who made the discovery on August 17, 1896 that started the Klondike Gold Rush.

|

| Klondikers buying miner's licenses at Customs House, Victoria, BC, 21 February 1898 (courtesy British Library). |

When Henderson met the three men, he told Carmack about the gold coming out of the Gold Bottom, just as he had told everyone he'd come across. He encouraged Carmack to head upstream and stake a claim at Gold Bottom. Henderson believed fiercely in the unwritten prospector's code, which promoted the free exchange of information. He did, however, make one auspicious exception.

Carmack asked Henderson about the chances at Gold Bottom. Henderson, looking at Carmack's aboriginal brothers-in-law, replied, "There's a chance for you, George, but I don't want any damn Siwashes staking on that creek."

Henderson had been obsessed by the idea of finding gold since reading Alaskan histories as a child in Nova Scotia. At fourteen, believing the southern hemisphere offered the best opportunity, he signed on to a sailing ship. He traipsed all over New Zealand, Australia and other remote corners, finding little gold. After five years, he decided to try the northern hemisphere. He worked his way up the Rockies to Colorado and 14 years later, with so many others, headed north to Alaska.

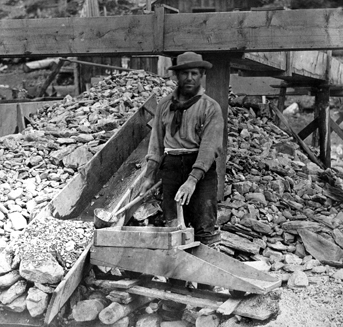

Henderson took to heart the prospector's way of life, and wore his broad-brimmed miner's hat proudly. But he broke the code he lived by when he denied Skookum Jim and Tagish Charley, and it cost him dearly.

Carmack and his group didn't set out for Gold Bottom immediately. Carmack was more interested in logging than panning and hoped to cut logs at Rabbit Creek to float to the Forty Mile mill. The native Californian's aspiration was to become the chief of the Tagish tribe, though he was white. His Tagish wife, Kate, was the daughter of a chief. Carmack was more indolent than anything else; no one took him seriously as a prospector.

Skookum Jim was Carmack's opposite. He was Tagish and desperately wanted to be a prospector. Henderson's pejorative remark about "Siwashes" had hurt.

When the trio reached Gold Bottom, they panned but didn't stake a claim. Before heading over the domed mountain divide to try their luck at Rabbit Creek, the natives asked Henderson for some tobacco. Despite the code that disallowed denying anything to a fellow prospector, Henderson refused to sell to them. His decision would leave him "up a creek" with no claim to stake.

When they left, Carmack told Henderson that he would send word back with one of the natives if he found anything on Rabbit Creek. They struggled across the rugged terrain, through bush and swamp, plagued by hordes of mosquitoes and gnats. Finally they reached the fork of Rabbit Creek and pressed on a kilometer further before making camp. It was August 16.

The next day, after panning out a few traces of gold, one of them exposed a thumb-sized nugget. Exactly who found the gold is unclear. Carmack claimed it was he, but Skookum Jim and Tagish Charley maintained that Carmack was sleeping under a birch tree when Jim, who was washing a dishpan in the creek, made the find.

They exposed a rim of bedrock streaked with gold. Carmack, Skookum Jim and Tagish Charley staked their claims the next day and renamed the creek Bonanza. Carmack and Charley headed to Forty Mile to register their claims, without giving a thought to telling Henderson. But along the way they told everyone they met.

By the time Henderson heard about the discovery, the Klondike Gold Rush had started and all the claims along the Bonanza had been staked. The rush was short-lived. It ended in the summer of 1898 with the Spanish-American War and news of a strike at Nome, Alaska. Henderson never became wealthy, but he is now credited as co-discoverer.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom