Between the 1950s and the 1990s, the Canadian government responded to national security concerns generated by Cold War tensions with the Soviet Union by spying on, exposing and removing suspected 2SLGBTQ+ individuals from the federal public service and the Canadian Armed Forces. They were cast as social and political subversives and seen as targets for blackmail by communist regimes seeking classified information. These characterizations were justified by arguments that people who engaged in same-sex relations suffered from a “character weakness” and had something to hide because their sexuality was considered a taboo and, under certain circumstances, was illegal. As a result, the RCMP investigated large numbers of people. Many of them were fired, demoted or forced to resign — even if they had no access to security information. These measures were kept out of public view to prevent scandal and to keep counter-espionage operations under wraps. In 2017, the federal government issued an official apology for its discriminatory actions and policies, along with a $145-million compensation package.

Background: Cold War Espionage

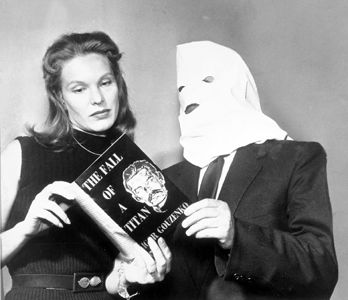

In 1945, the defection of Soviet cipher clerk Igor Gouzenko revealed that Canada had been infiltrated by a network of Soviet agents in both the civil service and the military and scientific establishments. (See Intelligence and Espionage.) In response, a royal commission was launched. It found that Canadian public servants had passed state secrets to Soviet agents. The government realized that it had no process in place to detect such security threats. So in 1946, it established a Security Panel. It was made up of a small, secret committee of top civil servants and members of the RCMP. The Security Panel was tasked with identifying civil servants whose loyalties were in doubt.

In 1948, a Cabinet directive stated that “maximum care” must be used to ensure that government employees were trustworthy. Investigation fell to the RCMP. It extended its anti-communist purge to individuals who were engaged in socially stigmatized behaviours. The RCMP created a new category for people who demonstrated “character weaknesses.” The reasoning was that individuals who gambled, committed adultery or drank heavily, for example, were vulnerable to blackmail because they had something to hide.

This reasoning extended to anyone engaging in anything that was then considered sexually taboo. Lesbians, gay men and bisexuals did not adhere to sexual conventions of that time. So it was thought that were also likely to violate political norms. They were therefore commonly associated with communism and spying.

At the time, people who engaged in same-sex relations were widely considered to be mentally ill and a menace to society. The law targeted sex between men, making it a criminal offence. (See Criminal Code.) It also made any activity that could potentially lead to sexual relations between two men illegal. In 1953, the law was extended to women. Thus, men or women who sought out opportunities to socialize together — for example, by dancing, congregating in a bar, or even attending private house parties — risked arrest.

Human rights laws did not protect against discrimination based on sexual orientation. That made it perfectly legal to fire someone from their job due to their sexuality. (See 2SLGBTQ+ Rights in Canada.)

DID YOU KNOW?

2SLGBTQ+ is an umbrella term that stands for people who are two-spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer (or questioning), or additional sexual orientations and gender identities, such as intersex and asexual.

Gay men, lesbians and bisexuals were therefore considered easy targets for Soviet manipulation. If threatened with exposure, it was thought, people would do anything to avoid the humiliation of having their sexuality revealed; even if it meant betraying their country. Mainstream media helped spread this fear. For example, the Globe and Mail ran an article in 1955 which stated:

“Exposure, not punishment, is what the normal homosexual — if we can say any homosexual is normal — fears. That is why homosexuals are found to be a danger if placed in positions where important Government secrets may reside. It is not that they are likely to be more traitorous than others, but that they are vulnerable to blackmail and might betray official secrets to preserve private ones.”

American Influence

Initiatives that targeted 2SLGBTQ+ civil servants as a security threat were not unique to Canada. In the United States, for example, CIA director Roscoe Hillenkoetter stated in 1950:

“the moral pervert is a security risk of so serious a nature that he must be weeded out of government employment wherever he is found. Failure to do this can only result in placing a weapon in the hands of our enemies.”

Pervert was a commonly used pejorative to describe 2SLGBTQ+ people. Also in 1950, a report entitled “Employment of Homosexuals and Other Sex Perverts in Government” was submitted to a US Senate subcommittee. It concluded that 2SLGBTQ+ staff were unsuitable for employment in the federal government because of their “degraded,” “illegal” and “immoral acts.”

Canada’s Security Panel was highly sensitive to American security concerns. Thus, when the United States stepped up its campaign to purge 2SLGBTQ+ people from federal posts in the early 1950s, Canada followed suit. One of the earliest firings occurred in 1952. A man working at Canada’s Communications Branch, which intercepted radio signals from the Soviet Union, was found to be gay. The individual’s loyalty and honesty were not in doubt; however, authorities feared that concerns over his sexuality could jeopardize intelligence sharing arrangements with the Americans.

Identification and Elimination of 2SLGBTQ+Staff

In 1952, a new Cabinet directive on security advised that security checks consider “defects of character” that might cause an employee to be “indiscreet, dishonest or vulnerable to blackmail.” Three years later, a more detailed directive reaffirmed this position. At the same time, the Canadian government prohibited 2SLGBTQ+ civil servants from all positions deemed sensitive. This included positions in the military, the RCMP and in foreign affairs.

In 1956, the RCMP formed a “character weakness” unit. Its purpose was to scrutinize civil servants’ backgrounds. Between the years 1958–59, a person’s sexuality became a primary focus of security investigations.

These investigations met with some resistance. The Security Panel’s liberal-minded members sought to restrict security probes to people with access to classified information. Prime Minister John Diefenbaker, for example, was in the process of drafting the Canadian Bill of Rights. He was uncomfortable with the use of “character weakness” to justify dismissals from the public service. Nevertheless, the Security Panel gave RCMP investigators the power to search for so-called sexual deviants in all government departments.

Beginning in 1959, the RCMP annually uncovered hundreds of confirmed, alleged and suspected 2SLGBTQ+ employees in government departments and agencies. These included such low-level security offices as the Central Mortgage and Housing Corporation, the Department of Public Works and the Unemployment Insurance Commission. People outside the public service were also investigated. This was part of a strategy to track down as many federally employed 2SLGBTQ+ individuals as possible.

By 1964–65, about 6,000 2SLGBTQ+ employees, predominantly gay men, were on file with the RCMP. The next year, this number climbed to 7,500. By 1967–68, continued surveillance and collaboration with other police agencies brought the total number of files to about 9,000. Only around one-third of these people were federal public servants.

The Department of External Affairs (DEA) and its embassies around the world were an area of concern. Members of the far right saw them as “a notorious cess-pool of homosexuals and perverts.” This view was partly due to a policy by the DEA to post bachelors to the Soviet bloc. This was because these positions were thought to be challenging posts for married men with families. As a result, the DEA was hit particularly hard by RCMP surveillance practices. High-profile examples of those targeted included two of Canada’s ambassadors to Moscow: David Johnson (1956–60); and John Watkins, (1954–56). Watkins died of a heart attack in 1964 following 27 days of interrogation by the RCMP regarding his sexuality.

Did you know?

John Wendell Holmes was a senior Canadian diplomat. He helped shape Canada’s post-war foreign policy. He was forced to resign from public service in 1960. Holmes joined the Department of External Affairs in 1943. He was posted to Moscow in the late 1940s. He was interrogated at RCMP headquarters in Ottawa in November 1959. Holmes disclosed his sexual orientation, but denied ever having been blackmailed by the Soviets. Holmes suffered a nervous breakdown because of the RCMP’s investigation and interrogation. His diplomatic career ended abruptly when he was 49 years old. Holmes moved on to a successful academic career. His published works are considered essential guides to the history of Canadian foreign policy.”

A research project was carried out between 1959 and 1962. Its goal was to see if distinctions could be made between 2SLGBTQ+ staff who did or did not pose a security threat. The study concluded that sexual orientation was not a matter of choice. This crucial finding undermined the belief that homosexuality was a “character weakness.” It helped persuade the Security Panel that a new approach was needed.

By the mid-1960s, the enthusiasm for purging 2SLGBTQ+ employees from the public service mellowed. There were fewer firings. By the late 1960s, 2SLGBTQ+ employees in jobs with lower security clearance levels were more likely to be denied promotion than face discharge.

Rather than moderate its hardline stance, however, the RCMP redirected and escalated the hunt inward on its own members. This was done through a series of investigations; they reached a peak in the late 1960s and died out in the early 1970s. The RCMP developed a series of indicators believed to identify gay men. The indicators ranged from driving white cars, to wearing rings on pinkie fingers, to wearing tight pants.

In 1969, a report by a royal commission on security (The Mackenzie Commission) recommended that 2SLGBTQ+ employees be allowed to work. But it also said that they “should not normally be granted clearance to higher levels; should not be recruited if there is a possibility that they may require such clearance in the course of their careers; and should certainly not be posted to sensitive positions overseas.”

RCMP Surveillance of Suspected 2SLGBTQ+ Civil Servants

Methods used by the RCMP to detect 2SLGBTQ+ civil servants included photographing men who frequented places where gay men were known to gather, including bars. Years later, one individual recalled the somewhat clandestine approach used by the police:

“We even knew occasionally that there was somebody in some police force or some investigator who would be sitting in a bar…. And you would see someone with a… newspaper held right up and if you…looked real closely you could find him holding behind the newspaper a camera and these people were photographing everyone in the bar.”

Police also set up surveillance in public parks where men cruised for sex. Agents were known to try to entrap men in parks by posing as gay men. The RCMP also befriended and recruited gay men as informers. (Lesbians, however, rarely cooperated.) A sergeant who was gay was caught and then removed from the RCMP after surveillance was set up of his bedroom. This demonstrated the lengths to which the Mounties were willing to go.

In 1963, the RCMP tried to map where 2SLGBTQ+ communities gathered in Ottawa. The goal was to put these places under surveillance. However, the map was soon covered in so many dots that it proved useless.

The “Fruit Machine”

Beginning a few years earlier, the government began funding and sponsoring research into methods for “scientifically” detecting 2SLGBTQ+ individuals. This research and the device used to test sexuality came to be known as the “fruit machine.” (Fruit was a commonly used pejorative for gay.) The device attempted to test a subject’s sexuality by monitoring their pupils when exposed to erotic pictures; it was believed that pupil dilation indicated sexual arousal.

The RCMP was unable to recruit enough test subjects who were gay. There was reluctance among “normal males” within the force to volunteer because they feared being misidentified as gay. Test results were deemed inconclusive. By 1967, the fruit machine was abandoned. It was decided that a scientific means for identifying homosexuality was out of reach.

End of the Purge

The Cold War against 2SLGBTQ+ civil servants did not end in the late 1960s. In 1973, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau confirmed that suspected homosexuality was one of the factors the government considered before clearing any federal employee to handle classified documents.

Reflecting the climate of fear that the RCMP investigations continued to create in the 1970s, a woman who worked as a public servant at that time later recalled:

“you always presumed when you were working with the government, ‘Yes, okay, you’re a lesbian.’ You just don’t let anyone else know because of job security.… it was a scary time for anyone who was gay.”

The RCMP security campaign continued until at least the late 1980s and early 1990s. Around that time, official policies excluding 2SLGBTQ+ were changed. This followed decades of lesbian and gay activism and legal challenges.

DID YOU KNOW?

Michelle Douglas began a promising career in the Canadian Armed Forces in 1986. She was honourably discharged for being a lesbian. In 1990, she launched a successful lawsuit against the military. It resulted in the end of its discriminatory policy against gays and lesbians. See Canada’s Cold War Purge of 2SLGBTQ+ from the Military.

Apology and Compensation

In 1990, Michelle Douglas, a former officer with the Special Investigation Unit (SIU), launched a successful lawsuit against the military, which had discharged her for being a lesbian. The case resulted in the ending of the long-standing discrimination and purging of gays and lesbians in 1992. Prime Minister Brian Mulroney denounced the purge as “one of the great outrages and violations of fundamental human liberty.”

In 2015, a group calling itself the We Demand an Apology Network — led by Martine Roy, Alida Satilic and Todd Ross — pressed the government to issue an apology for its purge from the public service, RCMP, Canadian Security Intelligence Service and military.

In November 2017, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau apologized in the House of Commons for discrimination done or condoned by the federal government and its agencies against 2SLGBTQ+ individuals. The apology came with a $145-million compensation package. It included $110 million to be paid out as part of a class-action lawsuit settlement for civil servants whose careers suffered because of discriminatory actions against them. It also included $15 million for historical reconciliation, education, and memorialization efforts. The compensation package is administered by the LGBT Purge Fund.

See also: Canada’s Cold War Purge of 2SLGBTQ+ from the Military; Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS); 2SLGBTQ+ Refugees in Canada; Human Rights; Canadian Human Rights Commission; Canadian Human Rights Act; Civil Liberties.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom