The centre-left Liberal Party of Canada has dominated federal politics for much of Canada’s history. Its formula for success, developed under the leadership of Sir Wilfrid Laurier, is to straddle the political centre. Liberals have formed numerous governments and provided Canada with 10 prime ministers. They include William Lyon Mackenzie King, Lester B. Pearson and Pierre Trudeau. Due to their electoral dominance, the Liberals are sometimes seen as Canada’s “natural governing party.” But the party has also experienced defeat and internal divisions. After the Sponsorship Scandal in the early 2000s, the party spent a decade in the political wilderness. In October 2015, the Liberals surged from third place to first in the House of Commons, winning a majority government under Justin Trudeau. The Liberals then won two consecutive minority governments in 2019 and 2021 before Trudeau resigned in early 2025. He was replaced as leader and prime minister by former Bank of Canada and Bank of England governor Mark Carney, who was elected with a minority government on 28 April 2025.

Origins of the Liberal Party

The Liberal Party of Canada has its roots in opposition parties that formed in the colonies of British North America. Representative assemblies were established in Nova Scotia (1758), Prince Edward Island (1773), New Brunswick (1784) and Upper and Lower Canada (1791). The parties developed in opposition to the oligarchies (small groups of elites) that controlled the colonial governments.

In Lower Canada (now Quebec), a primarily francophone party (the Parti Canadien) called for responsible government. This was the idea that Cabinet could only govern if it enjoyed the confidence of the elected assembly. In 1826, the Parti Canadien became the Parti patriote. Under its leader, Louis-Joseph Papineau, the party pushed for greater authority for the elected Legislative Assembly, which it dominated. The party became more radical over time, as its ambitions were frustrated. Ultimately, this led to the failed rebellions of 1837–38. In Upper Canada (now Ontario), the opposition party was known as the Reformers. It was led by William Lyon Mackenzie. Its more radical members also took part in the rebellions.

In the Maritimes, Joseph Howe led a 10-year struggle for responsible government. It was finally successful in 1848. In the Canadas, an English-French political alliance was formed when Reformers in Upper Canada (under Robert Baldwin) joined with Reformers in Lower Canada (under Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine) to form a government. They did so in 1842 and again in 1848 in the united Province of Canada. They won responsible government in 1848, shortly after it was granted in Nova Scotia.

The Reform Party in Upper Canada split in 1849 with the emergence of a radical faction known as the Clear Grits. The Grits believed that French Canadians had too much influence in the government. Therefore, they pushed for representation by population. This would have assigned more seats to primarily English-speaking Upper Canada at the expense of French-speaking Lower Canada.

In 1854, moderate Reformers formed a coalition government with the Conservatives. This left the Clear Grits in opposition with the Parti rouge (as the Reform Party in Lower Canada was now known), led by Antoine-Aimé Dorion. The Reformers and Clear Grits came together under George Brown. They adopted the Liberal name in 1857. Soon, the Liberals were the dominant party in Upper Canada. Though divided on issues like rep by pop, they formed an uneasy alliance with the Rouges. This lasted until Liberal leader George Brown joined the Great Coalition, the 1864 alliance that helped bring about Confederation.

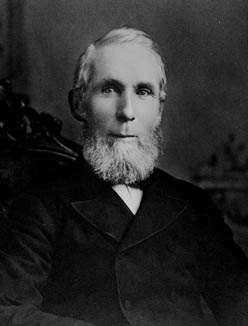

Alexander Mackenzie

After Confederation, the Liberals of Ontario, the Rouges of Quebec and the Reformers in the Maritimes formed a party under the Liberal name. They had little success against the political wiles of Conservative Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald and his federal coalition. Later, however, the Liberals developed successful provincial parties.

After the downfall of Macdonald’s government over the Pacific Scandal, the stonemason Alexander Mackenzie formed Canada’s first Liberal government in 1873. A severe economic depression, and Mackenzie’s lack of political vision, led to Macdonald’s re-election in 1878 on a platform of trade protection. The resulting National Policy of tariff protection was vigorously opposed by Edward Blake. He was a Toronto lawyer and ex-premier of Ontario who led the Liberal Party from 1880 to 1887. (Blake was the only federal Liberal leader, until the 21st century, never to become prime minister.)

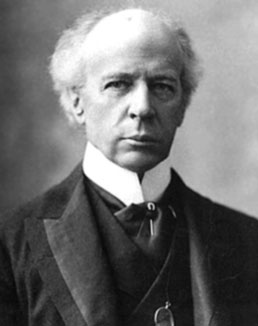

Wilfrid Laurier

Wilfrid Laurier was chosen party leader by a reluctant federal Liberal caucus upon Blake’s advice in 1887. Laurier gradually broadened the party’s base in his home province of Quebec. Laurier had risen to prominence there by preaching the virtues of racial conciliation. Laurier capitalized on the Conservatives’ mishandling of the Manitoba Schools Question. He won the election of 1896 on a platform of provincial rights. He went on to win the next three elections by copying Macdonald’s formula — a nationwide coalition of forces and an agreement between French and English Canadians. Under Laurier, more traditional principles of Liberal reformism were tempered with pragmatism and patronage.

A clever and eloquent politician, a true legend in his own time, Laurier has been judged in a variety of ways. He built his electoral coalition in English Canada on the backs of Liberal provincial premiers. Laurier brought them into his Cabinet as power brokers for their regions. He endorsed the aggressive immigration policy of his Manitoba minister, Clifford Sifton, to settle the West. Laurier also entered the same kind of railway-building collaboration, with the Grand Trunk and Canadian Northern, that his caucus had strongly opposed in the 1880s when it was championed by Macdonald.

Differences of principle still distinguished the Laurier Liberals from their Conservative opponents. In external affairs, the Liberals created the Royal Canadian Navy, rather than contributing to the British navy. (See also Naval Service Act.) In commercial policy, Laurier achieved the long-held Liberal goal of a reciprocal trade agreement with the United States. But it was a victory that proved to be his undoing. Reciprocity alienated the protection-minded business community whose support he had cultivated. The Liberals went down to defeat in the 1911 election in the face of the Conservative Party’s anti-Americanism. Laurier soldiered on as leader. He watched in despair as the First World War conscription issue nearly destroyed his party by shaking the solidarity of its English-French alliance.

William Lyon Mackenzie King

William Lyon Mackenzie King became the Liberal leader in 1919. He went on to become the longest-serving prime minister in Canadian history. He was PM from 1921 to 1948, except for two periods in opposition, in 1926 and 1930–35. King’s Liberals led the country into the Great Depression and, later, through the Second World War.

King’s political longevity has been ascribed to his uncanny ability to blur political issues to maintain support among different groups. These included western free-trade farmers and protectionist manufacturers in central Canada. King shrewdly understood the importance of sustaining support in Quebec, especially during the Second World War. He had a talent for attracting strong Cabinet ministers with regional power bases and made use of their skills and connections. He also introduced progressive policies such as social welfare programs while mollifying businesses.

Louis St-Laurent

King’s hand-picked successor was Louis St-Laurent. He was admired by the bureaucratic and business elites more than King had been. But St-Laurent disregarded party organization and was overly dependent on the Ottawa bureaucracy. His regime saw the collapse of King’s great Liberal alliance. It also marked the start of the party’s alienation from Western Canada. St-Laurent narrowly lost to Conservative John Diefenbaker in 1957. The Liberal Party has been struggling ever since to regain its previous high levels of support in the West.

Lester B. Pearson

Lester Pearson became Liberal leader in early 1958. The Nobel Peace Prize-winning former diplomat and secretary of state for external affairs needed three elections to win federal power in 1963. It was largely thanks to the skills and convictions of his close adviser, Walter Gordon, that he was able to build the party organization. But one price of Gordon’s reforms was the further alienation of the West from what had become a Toronto-dominated party. Gordon received the credit for winning a minority victory in 1963. He was blamed for recommending another election in 1965. It returned the Liberals as a minority government once more. Pearson’s government never achieved a majority. But it accomplished much in its five years in office. It created a national medicare program, the Canada Pension Plan and a new Canadian flag.

Pierre Trudeau

Pierre Trudeau succeeded Lester Pearson in 1968. It was a hotly contested leadership campaign. Under Trudeau, French Canadians achieved a greater place within the party and the federal government than ever before. Trudeau had a lot of personal charisma. He was dedicated to federalism and to combating the separatist forces of Quebec nationalism. These factors lay at the heart of his early electrifying appeal to the public — known as Trudeaumania. But these factors also led to the strong animosities Trudeau later felt from English Canadian voters.

Based on its strength in central Canada, the Liberal Party managed to remain in office until 1979. It was in power again from 1980 to 1984. Under Trudeau, the Liberals “patriated” the Constitution. They also introduced the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1982. However, the party continued to scramble unsuccessfully to rebuild their position in the West.

John Turner

Pierre Trudeau stepped down as leader in 1984. He was succeeded by John Turner, his former finance minister. Turner was sworn in as prime minister on 30 June 1984. He quickly called a general election. He hoped to profit from the Liberals’ brief surge of popularity in public opinion polls. But Turner didn’t have an adequate organization or platform. He also lacked an appealing personal campaign style. Turner led the party to a shattering defeat. The Liberals won only 40 seats in the House of Commons. The Conservatives under Brian Mulroney won 211 seats.

For the next four years, the Liberal Party was plagued by problems. In the 1988 election, the central issue was free trade. (See also Canada and NAFTA.) Turner ran a strong campaign that appealed to nationalism. He capitalizing on the anxiety people felt in response to the Conservatives’ plan to sign a free trade agreement with the US. He brought the party back to a respectable position in the House of Commons, winning 82 seats. He then stepped down as leader.

Jean Chrétien

Jean Chrétien became Liberal leader in 1990. At the time, the party was disorganized and almost bankrupt. His support of the Conservatives’ Charlottetown Accord cost the Liberals in Quebec. But the Chrétien Liberals focused on policy development and organization. Because of this, they were well prepared for the election of October 1993. They stressed job creation. They also released a detailed platform that addressed criticisms that the party would return to the high spending of past Liberal governments. The campaign was a triumph. The Liberals won a clear majority with 177 seats. The Progressive Conservative Party was almost wiped out. It fell from 154 seats to two. The NDP collapsed from 43 seats to nine. And the newly formed Bloc Québécois won 54 seats. Chrétien’s Liberal Party was the only national party that had seats in the House of Commons from every province. In the next two elections in 1997 and 2000, the Liberal Party was re-elected with majorities.

The Chrétien government embarked on an ambitious program to balance the federal budget. It was led by Finance Minister Paul Martin. He promised to eliminate the $42 billion federal deficit “come hell or high water.” The government did eliminate the deficit. But it came at the cost of large cuts to social programs and to provincial transfer payments. Chrétien largely ignored Quebec nationalists. He was confident that he was providing good government and that this would be an effective answer to calls for Quebec sovereignty. The flaw in this approach was revealed in the 1995 Quebec referendum. The federal side won by the narrowest of margins. Chrétien’s response to this near defeat was the Clarity Act. The federal government declared that it would only negotiate Quebec’s separation if a strong majority had voted yes in a referendum based on a clear question.

Paul Martin

Paul Martin finally achieved his destiny only to be defeated by his own accidents and the accidents of history. As Chrétien’s time in office wore on, he faced internal opposition from supporters of Paul Martin, his long-time rival. Chrétien feared he might lose a confidence vote at a Liberal convention. So he announced in 2002 that he would step down. Martin became party leader and prime minister in 2003. He promised to strengthen health care and improve Canada’s standing in international affairs. He also said he would address what he called the country’s “democratic deficit” by increasing the powers of ordinary MPs.

But Martin’s government was immediately besieged by the worsening Sponsorship Scandal. Martin tried to distance himself from the affair by appointing the Gomery Commission to investigate. In the election on 28 June 2004, the party was reduced to a minority. As he tried to address multiple priorities, Martin often appeared unable to make decisions. The Gomery report cleared Martin of any wrongdoing in the Sponsorship Scandal. But the report confirmed allegations of corruption in both the bureaucracy and the Quebec wing of the federal Liberal Party. The party was defeated in the election on 23 January 2006. On election night, Martin announced his retirement as party leader.

Stéphane Dion

In December 2006, Liberals chose former Cabinet minister Stéphane Dion as their new leader. Dion inherited a disorganized and dispirited party. It was also in debt after enduring years of internal strife between the Chrétien and Martin camps. In 2007 and 2008, the Liberals backed away from chances to defeat the minority Conservative government and force an election. Prime Minister Stephen Harper took the matter into his own hands by calling an election for 14 October 2008. The centrepiece of the Liberal campaign was the “Green Shift.” It promised to lower income taxes and raise a carbon tax on greenhouse gas emissions. But it failed to capture public support. The Liberals were reduced from 95 to 77 seats in the Commons. On 20 October, Dion announced his resignation as party leader.

However, when Parliament met in November, the opposition parties, including the Liberals, agreed to vote down the government and ask the governor general to appoint Dion as prime minister. To avoid defeat, Harper had Parliament prorogued until January. The Liberals then moved quickly to replace Dion. Former journalist and academic Michael Ignatieff was installed as leader.

Michael Ignatieff

Despite vigorous attacks on the Harper government, the Liberals were unable to gain traction with Michael Ignatieff as leader. The party gambled in March 2011. It combined with other opposition parties to bring down Harper’s minority government and force an election. But NDP leader Jack Layton upstaged Ignatieff during the campaign. The Conservatives won the election with a majority government. The Liberals won only 34 seats and finished behind the NDP in third place. It was the worst showing in the party’s history.

Ignatieff announced the next day that he would step down as leader. Bob Rae, a Liberal MP and a former NDP premier of Ontario, became interim Liberal leader later that month. Liberals then began a period soul-searching over what had reduced Canada’s once-dominant federal party to a distant third-place standing.

Justin Trudeau

In 2008, Justin Trudeau, a former schoolteacher and the eldest son of Pierre Trudeau, was elected to Parliament. In 2013, Trudeau became leader of the party in a landslide vote. In the 2015 election campaign, Trudeau overcame public doubts that he was too young and inexperienced to be prime minister. But Trudeau became the chosen figure of change for voters seeking an end to nine years of Conservative rule under Stephen Harper. The Liberals won a majority government. Justin Trudeau became Canada’s 23rd prime minister.

Trudeau made headlines by forming a Cabinet with an equal number of women and men, a first in Canada. (When asked why, he said, “Because it’s 2015.”) In its first two years, Trudeau’s government admitted 40,000 Syrian refugees to the country. It cut the personal income tax rate on middle-income earners while increasing it for wealthier Canadians. It also legalized assisted dying in certain circumstances. It legalized marijuana and implemented a 10-year, $55 billion National Housing Strategy. It also reformed the Family Allowance as the Canada Child Benefit (CCB). The government also launched the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls.

The Trudeau Liberals faced significant challenges in foreign affairs. This was especially true of Canada’s relations with the United States, China and Saudi Arabia. Trudeau enjoyed a good relationship with US president Barack Obama. But his dealings with President Donald Trump (elected in 2016) were strained. The challenge came both from Trump’s unpredictability and his desire to cancel the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Protracted negotiations led to an agreement in November 2018: the Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA).

Trudeau’s Liberals were reduced to a minority government in 2019. They were re-elected with a minority in 2021. On 22 March 2022, the Trudeau government struck a supply-and-confidence agreement with Jagmeet Singh and the NDP. The NDP agreed to support the government in all confidence motions until June 2025. In exchange, the Liberals would implement certain NDP policy priorities, most notably dental care for low-income Canadians and a national pharmacare program.

As part of the agreement, the Trudeau government increased annual sick leave for people in federally regulated workplaces. It introduced a law banning scab workers at federally regulated workplaces during a strike. It created a roundtable to implement the recommendations of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. The Trudeau government also introduced the Canadian Dental Care Plan (CDCP). The program was planned to eventually cover one quarter of Canadians without private dental plans — about 9 million people — with a projected cost of $13 billion over five years.

However, Pierre Poilievre was elected as the new leader of the Conservative Party in September 2022. As leader of the Opposition, Poilievre pounded away relentlessly at Trudeau and the Liberal Party’s policies. Claims that “Canada is broken” and that Poilievre and the Conservatives were the only ones who could fix it became Conservative Party gospel. By late 2024, Poilievre had built a commanding lead of 20+ points in the polls. There was a wave of resignations from both caucus and cabinet as many Liberals anticipated an electoral bloodbath. Many observers predicted a large majority government for the Conservatives in an upcoming election.

On 6 January 2025, after months of speculation about his political future and three weeks after Chrystia Freeland’s abrupt resignation from Cabinet, a beleaguered Trudeau announced that he would resign as Liberal leader and prime minister.

Mark Carney

On 16 January 2025, former Bank of Canada and Bank of England governor Mark Carney made his first foray into politics, announcing he would run for the leadership of the Liberal Party of Canada. Within days, newly inaugurated US president Donald Trump began his second term by threatening a trade war with Canada with the stated goal of annexing it as the 51st state. Nationalism in Canada soared, and concerns over the country’s sovereignty grew — as did concerns over Poilievre’s ability to stand up to Trump, given their similarities in style, rhetoric and policy positions.

On 9 March 2025, Carney was elected — on the first ballot with more than 85 per cent of the vote — to replace Justin Trudeau as leader and prime minister. Carney became the first Canadian to become prime minister without previously serving as a Member of Parliament.

Carney was sworn in as the new Liberal leader and prime minister on 14 March 2025. His first move was to scrap the consumer carbon tax, thereby eliminating the signature issue that Poilievre had built his platform around: a “carbon tax election.” Carney pointedly made his first official foreign visit not to the US, as was customary, but to France. This was followed by visits to Britain, where he met with King Charles III, and Iqaluit, where he unveiled plans for a $6 billion early warning radar system along the Canada-US border into the Arctic. He also announced $420 million worth of new investments in protecting Canada’s Arctic sovereignty.

By 24 March 2025, when Mark Carney called a snap election for 28 April, the polls had the Liberals and Conservatives in a dead heat. But the momentum continued to be in the Liberals’ favour. A poll issued by 338Canada on 28 March showed the Liberals with 41 per cent support nationally compared to 37 per cent for the Conservatives. Many polls also showed the Liberals with sizable leads in vote-rich Ontario and Quebec.

However, Carney’s lack of political and campaign experience showed, as he made a series of early stumbles and unforced errors. But in the end, the election proved to be a two-way race. The Liberals and Conservatives combined for 85 per cent of the vote. The Liberals won 169 seats (3 short of a majority) with 43.8 per cent of the vote, while the Conservatives received 41.3 per cent and 143 seats. A surprisingly high number of races were decided by very narrow margins of only a couple dozen or a few hundred votes. The Liberals received the largest share of the vote for a winning party since 1984. It was also the first election since the 1930s that two parties both finished with more than 40 per cent of the vote. Voter turnout was a robust 68.7 per cent, the highest since 1993 but still lower than some pundits had predicted, given the high-stakes nature of the election.

Many pre-election polls predicted a Liberal majority government, but the Conservatives fared better than expected, increasing their seat total by 23. The Liberal victory was effectively secured by the switch in allegiance to Carney by NDP voters nationwide and Bloc voters in Quebec. Carney’s ability to convert what was likely to be a devastating defeat into a fourth consecutive Liberal government was nothing short of stunning, particularly for a political neophyte. Writing in the Walrus, political commentator David Moscrop called it “one of the most remarkable comebacks in Canadian history — maybe the most remarkable.”

After the election, Prime Minister Carney said he would ensure that a by-election is held in Alberta “as soon as possible… no games, nothing, straight,” to allow Pierre Poilievre, who lost his seat in the election, the chance to win a seat in Parliament. The next session of Parliament was scheduled to begin on 26 May. Carney announced that King Charles III would deliver the Speech from the Throne — an assertion of Canada’s sovereignty that many saw as a clear signal to Donald Trump, who has long admired the British Royal Family. Carney also continued to distance himself from the policies of Justin Trudeau by flat out refusing to have his minority government form a partnership arrangement with the NDP, which was reduced to seven seats in the House.

Perhaps most significantly, Carney laid out five main priorities for his government: (1) increase Canada’s economic resilience by breaking down interprovincial trade barriers by 1 July 2025; (2) appoint a cabinet and have it sworn in by the week of 12 May; (3) quickly introduce tax reform and ramp up the construction of new homes across the country; (4) hire 1,000 new Border Services officers and 1,000 new RCMP officers and add $31 billion in defence spending with the goal of reaching NATO’s spending benchmark of 2 per cent of GDP by 2030; and (5) reduce immigration to “sustainable levels” by lowering the amount of temporary workers and international students admitted to Canada from 7.3 per cent of the population to 5 per cent.

Internal Disputes

As with any broadly based party, there are always small but vocal groups that oppose the dominant view of the leadership. In British Columbia in the 1950s, many provincial Liberals formed a party with the right-wing Social Credit movement, to the dismay of the federal party. In the 1960s, Ross Thatcher, the Liberal premier of Saskatchewan, strongly opposed the welfare liberalism of Prime Minister Lester Pearson. Both conflicts damaged the federal party’s credibility in the West.

Since the 1960s, all provincial Liberal parties have had separate organizations. They have often pursued policies at that are odds with the federal party.

Throughout the party’s history, there has also been internal tension between the forces of continentalism and nationalism. This became most obvious during the 1960s, when Walter Gordon led the effort to limit the growth of foreign control in the economy. (See Foreign Investment; Economic Nationalism.) Gordon faced many setbacks. But he continued to push his ideas within the party. Meanwhile, other dissidents quit the party. For example, Cabinet ministers James Richardson and Eric Kierans quit the Trudeau government over policy issues (language policy for Richardson, economic policy for Kierans).

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, there were tensions between the left and right wings of the party. The conflict was mainly between Pierre Trudeau and John Turner and their respective followers. Turner quit his post as finance minister in 1975. He then played the role of Liberal dauphin-in-exile for almost a decade.

Later disputes in the party had less to do with policy than leadership. Internal conflicts began after the party’s 1984 convention. Jean Chrétien placed second to Turner. Turner’s supporters accused Chrétien of undermining the new leader behind the scenes. Similar accusations emerged from the Chrétien camp after he defeated Paul Martin for the leadership in 1990. Tensions continued throughout Chrétien’s term as prime minister. It led to his decision to step down in 2002.

Paul Martin elected leader of the Liberal Party of Canada

Canadian prime minister Jean Chrétien (left) and former finance minister Paul Martin celebrate after Martin was elected the new leader of the Liberal Party of Canada in Toronto, Ontario, 14 November 2003.

(photo by Donald Weber, courtesy Getty Images)

Financial Support

Traditionally, the Liberal Party raised election campaign money from big business and, to a lesser extent, small entrepreneurs. (See Political Party Financing in Canada.) After the introduction of the Election Expenses Act (1974), reliance on big business declined in favour of tax-deductible member donations and direct subsidies from the public purse. (See Canadian Party System). Corporate contributions all but disappeared in 2004. New legislation banned corporations and trade unions from contributing to political parties. In 2004, corporate and trade union contributions to candidates were strictly limited. In 2006, they were banned. To make up for the shortfall, parties began to receive public funding based on the number of votes they received in the previous election. The Liberals relied heavily on the subsidy. It ended in 2015.

Politics of Pragmatism

The Liberal Party dominated Canadian politics throughout much of the 20th century. It survived in the 1920s, when its namesake was collapsing in Britain. It also survived in the 1990s, when “liberal” was a derogatory term in the US. The party’s success has reflected its ability to occupy the political centre. But it has still shown ideological flexibility. This has allowed the party to argue for higher government spending in one era and balanced budgets in the next, or to support free trade in some periods and then condemn it in others.

In the latter decades of the 20th century, the party’s emphasis on tolerance appealed to immigrants and urban voters. This allowed the party to portray its opponents in English Canada as small-minded. In Quebec, the rise of the Bloc Québécois and, later, the NDP created a major challenge. It made it difficult for the Liberals to maintain their traditional hold on the province — once the core source of its power. But the 2015 election proved that the Liberal Party’s flexible, centrist message still resonates in Quebec and much of Canada.

Liberal Party Leaders

|

Name |

Term (yyyy.mm.dd) |

|

2025.03.10 - present |

|

|

2013.04.14 - 2025.03.10 |

|

|

Bob Rae (acting) |

2011.05.25 - 2013.04.13 |

|

Michael Ignatieff Made permanent leader at the party national convention held in Vancouver, British Columbia. The delegates voted 97 per cent in favour of his leadership. |

2009.05.02 - 2011.05.24 |

|

Michael Ignatieff (acting) |

2008.12.10 - 2009.05.01 |

|

2006.12.02 - 2008.12.10 |

|

|

Bill Graham (acting) Designated interim leader until a new leader was elected in December 2006. |

2006.03.20 - 2006.12.01 |

|

Paul Martin Sworn in as Prime Minister on 12 December 2003. |

2003.11.14 - 2006.03.19 |

|

Jean Chrétien Sworn in as Prime Minister on 4 November 1993. |

1990.06.23 - 2003.11.13 |

|

John Turner Sworn in as Prime Minister on 30 June 1984. |

1984.06.16 - 1990.06.22 |

|

Pierre Elliott Trudeau Sworn in as Prime Minister on 20 April 1968 and again on 3 March 1980. |

1968.04.06 - 1984.06.15 |

|

Lester B. Pearson Sworn in as Prime Minister on 22 April 1963. |

1958.01.16 - 1968.04.05 |

|

Louis St-Laurent Sworn in as Prime Minister on 15 November 1948. |

1948.08.07 - 1958.01.15 |

|

William Lyon Mackenzie King Sworn in as Prime Minister on 29 December 1921 and again on 25 September 1926 and 23 October 1935. |

1919.08.07 - 1948.08.06 |

|

Daniel Duncan McKenzie (Acting) Following Laurier's death in February 1919, caucus members chose McKenzie to serve as acting leader until the 1919 convention. |

1919.02.17 - 1919.08.07 |

|

Wilfrid Laurier Sworn in as Prime Minister on 11 July 1896. |

1887.06.23 - 1919.02.17 |

|

1880.05.04 - 1887.06.02 |

|

|

Alexander Mackenzie Sworn in as Prime Minister on 7 November 1873. |

1873.03.06 - 1880.04.27 |

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom