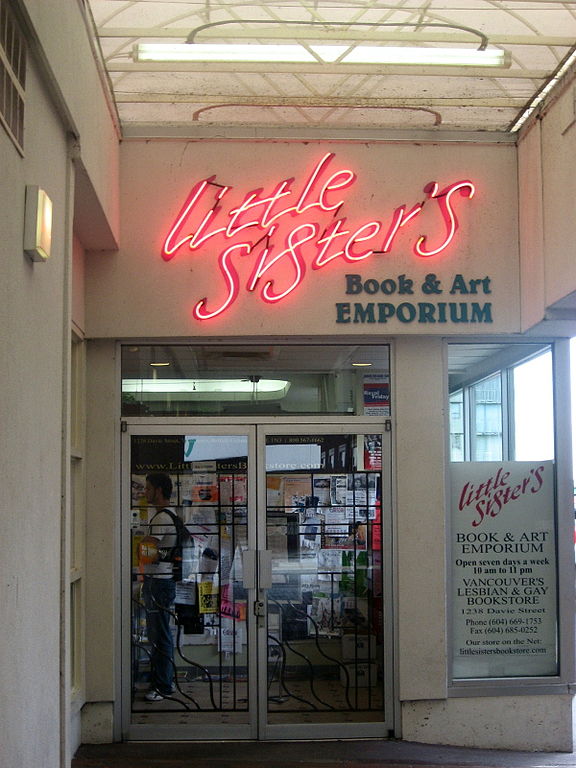

Little Sister’s Book and Art Emporium has long served as a source of 2SLGBTQ+ literature in Vancouver. Founded by Bruce Smyth and his partner Jim Deva in 1983, the bookstore has also been a social and political focal point for the communities it serves. As Deva has asserted, “More than anything else, Little Sister’s represents the power of community.” This power drove Little Sister’s decades-long legal battle with Canada Customs over censorship and the seizure of imported gay literature.

Censorship and Seizures

In 1984, Canada Customs began requiring foreign publishers of gay sex magazines to censor their publications to avoid border seizure. Magazines thus began appearing with black dots or markings placed over photographs and text, and “censored” printed across pages. The Customs Act (see Customs and Excise) and the Customs Tariff, first introduced in the 1800s, gave Canada Customs officials sweeping powers to seize, censor and ban books and periodicals coming into the country.

Canada Customs regularly seized gay and lesbian publications, including those without erotic content. Heterosexual pornographic material, meanwhile, had no trouble crossing the border. As was the case for Toronto’s Glad Day Bookshop and other 2SLGBTQ+ bookstores, nearly 75 per cent of books and magazines shipped to Little Sister’s were routinely seized.

Court Cases

The Little Sister’s case against Canada Customs was launched in March 1990. It eventually reached the Supreme Court of British Columbia. In January 1996, Justice Kenneth Smith crafted a ruling that vindicated and sought to preserve both Little Sister’s and Canada Customs. The decision affirmed the importance of both homosexual literature and the existing legislative regime of border censorship.

Justice Smith’s findings included that: gay and lesbian bookstores and publications were particularly vulnerable to the "arbitrary consequences" of Customs censorship; a "disturbing amount of homosexual art and literature that is arguably not obscene"was detained; and Customs officers were inadequately trained and lacked sufficient time to consistently do a proper job. In conclusion, Justice Smith wrote there were "grave systemic problems in the Customs administration." He nevertheless held that the prohibition on imported obscenity did not discriminate against gay men and lesbians.

A month after Justice Smith’s initial ruling, Little Sister’s returned to court. It sought an injunction to restrain Customs from detaining imported material destined for the bookstore until the systemic problems identified in the judgment had been remedied. Justice Smith declined to issue such an injunction. But he did issue a more limited one restraining Customs officials from subjecting Little Sister’s to a policy of heightened scrutiny “until the federal Crown satisfies [the Supreme Court of British Columbia] that the discretion of Customs officers in that office is guided by appropriate standards.”

Supreme Court Ruling

The bookstore’s case reached the Supreme Court of Canada on 16 March 2000. At that time, the store’s manager, Janine Fuller, stated: “I never get over that chilly feeling of violation, and of our community not being understood or respected. That is what fuels me.” She emphasized the importance “of access to read as a gay and lesbian person what we want to read,” adding, “How important is that first book when you were coming out, how important is the first novel that inspires you that you were not alone?”

The Supreme Court upheld the Customs Act as constitutional. But it also stated in its decision that Canada Customs carried out a campaign of harassment against the bookstore. Taking issue with poorly trained agents rather than with the law itself, the court agreed that the bookstore was singled out for seizure because Customs agents viewed gays and lesbians differently from mainstream culture. The court ordered Canada Customs to stop discriminating against Little Sister’s. The court also overturned one section of the Customs Act that forced importers to defend their materials. Instead, Customs agents were now required to justify the seizure in court.

Despite the 2000 Supreme Court ruling, Customs continued to seize material destined for the store “with renewed vigour,” according to Jim Deva. Little Sister’s took Canada Customs back to court in 2001. This led to another round of legal action lasting until 2007, when the bookstore ran out of funds to pursue the case. That same year, Deva stated, “The dilemma that haunts us to this day [is] How do we prove that the problem goes deeper than specific book seizures and lies rooted in a system that considers gay and lesbian material obscene?” He described the Supreme Court’s ruling as “hollow” and noted that despite ordering Canada Customs to stop discriminating, the Supreme Court “offered no oversight or review process to ensure Customs made the necessary changes.”

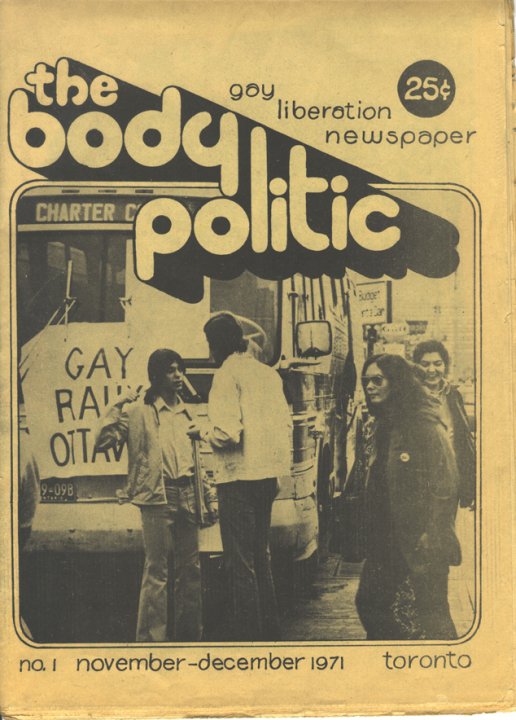

(See also Pink Triangle Press; The Body Politic; Queer Culture.)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom