Canada’s fifth province, Manitoba entered Confederation with the passing of the Manitoba Act on 12 May 1870. The Assiniboine, Dakota, Cree and Dene peoples had occupied the land for up to 15,000 years. Since 1670, it was part of Rupert’s Land and was controlled by the Hudson’s Bay Company. The Canadian government purchased Rupert’s Land at the behest of William McDougall, Manitoba’s Father of Confederation. No residents of the area were consulted about the transfer; in response, Louis Riel and the Métis led the Red River Resistance. It resulted in an agreement to join Confederation. Ottawa agreed to help fund the new provincial government, give roughly 1.4 million acres of land to the Métis, and grant the province four seats in Parliament. However, Canada mismanaged its promise to guarantee the Métis their land rights. The resulting North-West Resistance in 1885 led to the execution of Riel. The creation of Manitoba — which, unlike the first four provinces, did not control its natural resources — revealed Ottawa’s desire to control western development.

Background: Rupert’s Land

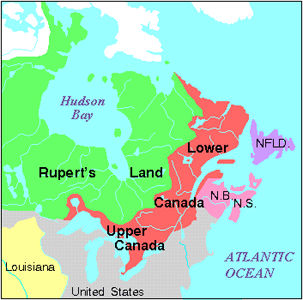

When Confederation took place in 1867, the new Dominion of Canada reached only from the Atlantic Ocean to the Great Lakes. West of Ontario, the territory now called Manitoba was part of Rupert’s Land. It was split between First Nations, European settlers, the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) and a Métis population (people of mixed European and Indigenous ancestry). The Assiniboine, Dakota, Cree and the Dene peoples had occupied the land for 12,000 to 15,000 years. The Ojibwa had arrived about 300 years ago.

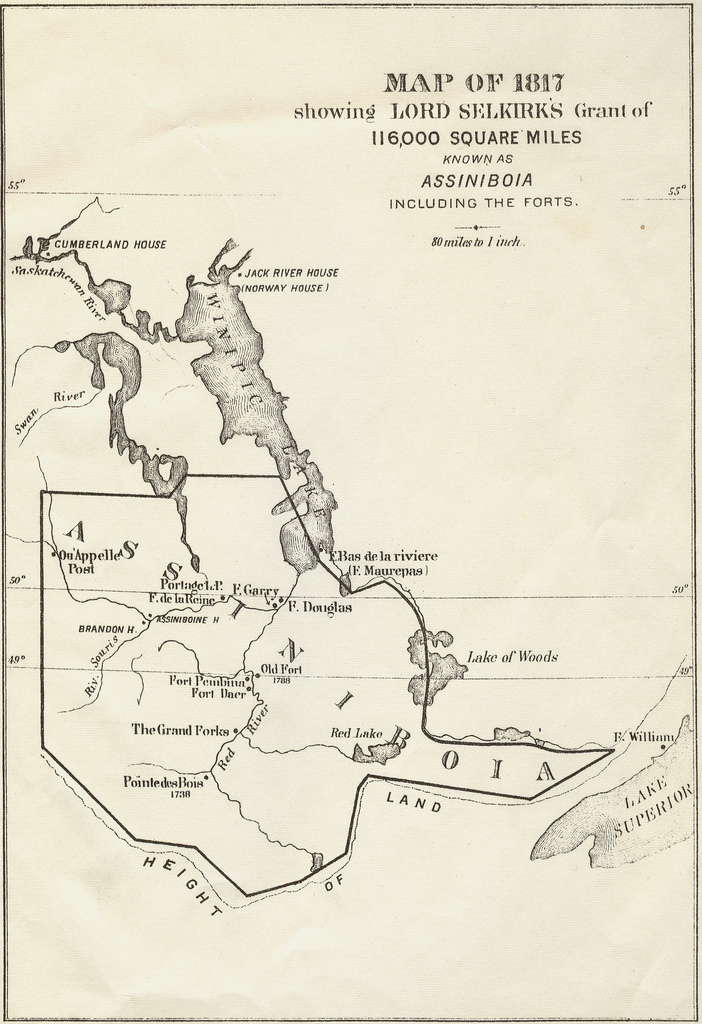

Beginning in 1670, the Hudson’s Bay Company controlled the vast territory of Rupert’s Land. It included all of modern-day Manitoba. The company tried to limit white settlement in the region to maintain its fur trade monopoly. But after 1812, European migrants began arriving in earnest. Many settled in land granted by the British Crown to Lord Selkirk, at the forks of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers in what is now Winnipeg. (See also The Forks.) It became known as the Red River Colony.

Transfer of Rupert’s Land (1869–70)

The United States purchased Alaska from Russia in 1867. This prompted fears in the Canadian and British governments that the US would try to take control of all the territory west and north of the Dominion of Canada, including Rupert’s Land. Determined that Rupert’s Land should be Canadian, the government of Prime Minister John A. Macdonald, with help from Britain, purchased the territory from the HBC. No residents of the area — including the First Nations, Métis and European settlers — were consulted about the transfer to Canada.

The HBC signed the deed of transfer surrendering its territory to the British Crown on 19 November 1869. The Crown, in turn, ceded the land to Canada. However, because of the political disruption of the Red River Resistance, the transfer did not come into effect until 15 July 1870.

Fathers of Confederation

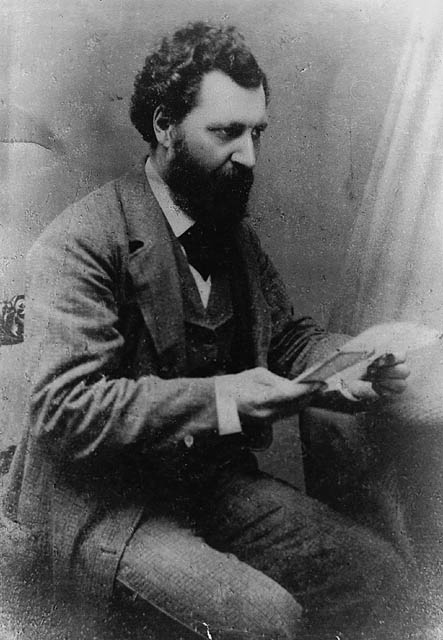

The Fathers of Confederation are the men who attended one or more of the conferences at Charlottetown, Quebec and London. William McDougall, Manitoba’s first lieutenant-governor, is considered a Father of Confederation for Manitoba.

A journalist and politician from Ontario, McDougall was a proponent of Confederation. He firmly believed that the only way out of the political impasse between Canada West and Canada East, and the only way to prevent Canada from becoming irrelevant in North America, was a union of the British colonies and expansion westward. He attended all three Confederation conferences — Charlottetown, Quebec and London.

McDougall was minister of public works in Sir John A. Macdonald’s government (1867). He introduced the resolution that led to the government’s purchase of Rupert's Land. He was also present in London to negotiate the acquisition of Rupert’s Land in 1868. On 28 September 1869, McDougall was named lieutenant-governor of Rupert’s Land and the North-Western Territory. He held that title until 12 May 1870 when Manitoba became a province.

On 30 October 1869, McDougall and his entourage entered the North-Western Territory via the United States. The convoy was turned back by the National Committee of the Métis of Red River on 2 November before McDougall could establish his authority at

Fort Garry. The Métis were angered that McDougall had sent a team of land surveyors to the Territory before a deal with the Hudson’s Bay Company had

been brokered. This was one of a series of events that precipitated the Red River Resistance.

McDougall then became a vocal opponent to the admission of Manitoba to Confederation. He argued that it did not possess a large enough population. Louis Riel is considered a founder of Manitoba. But he is not officially recognized as a Father of Confederation. His inclusion as one is the subject of much debate.

Red River Resistance (1869–70)

Many Indigenous people opposed the transfer of Rupert’s Land to the new Canadian government. But the stiffest resistance came from the Métis of the Red River Colony. They feared the loss of their land, their Roman Catholic religion, and their culture under Canadian control. In 1869, under Louis Riel, the Métis declared their own provisional government. It announced that it would negotiate the colony’s terms of entry into Confederation. A group of Protestants from Ontario, including Thomas Scott, disagreed with Riel’s group. Scott was court-martialed by Riel and executed by firing squad. (See Red River Resistance.)

After a long standoff followed by lengthy negotiations in Ottawa, the resistance came to an end. The Red River colonists agreed to enter Confederation. Four successive lists of rights were drafted by the provisional government; the final version became the basis of the Manitoba Act of 1870 (the federal legislation that created Manitoba). The final list demanded that Manitoba be admitted into Confederation as a province, not a territory; that the lieutenant governor of the new province speak both English and French; and that members of the provisional government not face legal consequences for their actions in the Resistance. Nevertheless, Riel feared prosecution for his execution of Thomas Scott. He fled to the US as British and Canadian troops arrived in the area.

Manitoba Act (1870)

The Manitoba Act received royal assent and became law on 12 May 1870. The Act gave Canada the lands it wanted; it created Manitoba as a “postage stamp-sized” province around the Red River Valley, amid the vast expanse of the North-West Territories. It granted the Métis title to their lands on the Assiniboine and Red Rivers.

The Manitoba Act essentially established a Métis province. Prime Minister John A. Macdonald thought the creation of a new province was premature. With its small population and size, it could not support itself financially.

Despite Macdonald's reluctance, Manitoba entered Canada as a province. English and French-language rights were safeguarded in the new legislature and the courts. Protestant and Roman Catholic educational rights were protected, but the right to education in either English or French was not. Ottawa agreed to pay subsidies to the new provincial government; roughly 1,400,000 acres of land were set aside for the Métis; and the province received four seats in the federal Parliament — strong representation considering the small population.

Unlike in other provinces at the time, the federal government retained control of Manitoba’s natural resources. Unallocated land was especially important; it would be sold to support the building of a Pacific railway. (See Canadian Pacific Railway.) The railway became an important hub for immigration. The new province of Manitoba thus entered Confederation as a province unlike the original four. Its creation revealed Ottawa’s desire to control western development and access to resources.

North-West Resistance (1885)

By the late 1870s, the Plains Indigenous nations of the West — the Cree, Siksika, Kainai, Piikani, and Saulteaux — were facing disaster. The great bison herds had disappeared, pushing people to near starvation. Much of their land had also been signed away in treaties. In 1880, Cree chief Mistahimaskwa (Big Bear) and Siksika chief Isapo-muxika (Crowfoot) founded the Blackfoot Confederacy to try to solve their people’s grievances.

Meanwhile the Métis people — still feeling vulnerable after the Red River Resistance — had grievances of their own. Their old life as fur traders and carriers for the Hudson’s Bay Company was disappearing, along with the bison on which they too depended. They were also waiting, without much help from the distant federal government, for reassurance that title to their homesteads and farms would be guaranteed. Poor harvests in 1883 and 1884 added to the province’s problems, along with an unsympathetic Dominion government back East.

In the summer of 1884, Louis Riel returned from exile in the US. That fall, he urged Métis and non-Métis settlers alike to sign a petition. On 8 March 1885, the Métis passed a 10-point “Revolutionary Bill of Rights.” It asserted Métis land claims and made demands of the Canadian government.

That March, armed resistors formed a provisional government and named Riel president. The Métis-led forces occupied Duck Lake near Batoche,

in present-day Saskatchewan. On 26 March, 100 North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) constables and citizen volunteers went to Duck Lake. The Métis and Indigenous resistance met the police outside the village. In the clash, 12 NWMP constables and

six resistance fighters were killed.

The Canadian government sent 3,000 soldiers to join the 2,000 already stationed in the West. They ran into staunch resistance from forces such as Big Bear’s. He objected to Canada’s plans to move his people onto a reserve. His warriors launched small-scale attacks on priests, an Indian agent and a trader, killing several people. The two sides fought again in the Battle of Batoche; Cree chief Poundmaker led the Indigenous forces to victory.

Canadian forces pressed on, capturing Batoche in May. Riel surrendered on 15 May. The resistance’s last act played out on 3 June at Loon Lake, with a small skirmish between the two sides. On 26 May, Poundmaker and other Indigenous leaders surrendered to Canadian troops. Riel was executed on 16 November 1885, followed by Cree leader Wandering Spirit on 27 November. The North-West Resistance was finished.

Land Rights and Numbered Treaties

Canada mismanaged its promise to guarantee the Métis rights to their land. After Manitoba entered Confederation, an influx of settlers from Ontario threatened to overwhelm the previous inhabitants.

Meanwhile, the federal government signed a series of Numbered Treaties with First Nations in Manitoba and other parts of the West. These treaties separately spelled out each First Nations’ constitutional relationship to the Crown. The treaties provided the federal government with land for industrial development and White settlement. The terms of agreement of the treaties are controversial and contested. (Hayden King, the director of the Centre of Indigenous Governance at Ryerson University, has argued that First Nations view the treaties as sharing agreements, while Canada views them as land surrenders.) The Numbered Treaties continue to this day to have legal and socioeconomic impacts on Indigenous communities.

Immigration and Boundaries

Between 1876 and 1881, some 40,000 migrants from Ontario settled in Manitoba. They pushed north past established boundaries and greatly expanded the new province. Settlers from Iceland, as well as Mennonite migrants and others populated the area.

In 1881, after years of political wrangling with the federal government, the province’s boundaries were extended to their present western position; they were also extended farther east, and north to 53° N lat. The current boundaries of the province were set in 1912. (See also Historical Boundaries of Canada.)

See also: Confederation: Collection; Confederation: Timeline; Louis Riel: Timeline; Métis National Council; Congress of Aboriginal Peoples; Indigenous Land Claims.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom