Everyone loves a good mystery. Canadian history is rich with stories of great secrets, unsolved crimes, and events that defy explanation. Among them are the following five mysteries, each shrouded in puzzling circumstances and unresolved endings.

1. The Mystery at Angikuni Lake

On 12 November 1930, fur trapper Joe Labelle entered a small Inuit community in Nunavut’s Kivalliq Region, on the shores of Angikuni Lake. (See also Fur Trade in Canada.) He discovered beached kayaks, dwellings filled with clothing, rifles and half-eaten meals, but no people. About 25 people had vanished. Labelle reported his findings to RCMP officers who verified his story. Sergeant J. Nelson later investigated Labelle’s report and visited the site. The RCMP spoke with trapper Armand Laurent, who said he had recently seen a big cylindrical object in the sky near the abandoned village.

Interest in the mystery grew in 1959 with the publication of Frank Edwards’s book, Stranger Than Science. Reports appeared in newspapers, books and magazines around the world describing the event as an alien abduction. In 1988, a group called Australian Skeptics contacted RCMP historian S.W. Horrall, who said there were no records of missing villagers or of Labelle’s having contacted the police or of a police investigation.

2. The Mackenzie River Ghost

In 1853, Augustus Richard Peers was a 33-year-old Hudson’s Bay Company fur trader and postmaster working in the Northwest Territories at Fort McPherson. He fell ill. When it appeared the end was near, Peers said that he didn’t want to be buried at Fort McPherson. However, it took six years before his bones were brought south to Fort Simpson.

A man named Roderick MacFarlane and a companion took the coffin containing Peers’s body and set out on a dogsled journey approximately 1,290 km south, along the banks of the Mackenzie River. MacFarlane later reported that many times enroute, wild animals menacingly approached the sled. Each time, he and his companion heard a strong and mysterious voice shout out, ordering the dogs to run. When they reached Fort Simpson, both claimed they felt a “ghostly presence” of the late Peers.

In 1955, R.S. Lambert told the story in his book, Exploring the Supernatural: The Weird in Canadian Folklore.

3. The Mystery of Tom Thomson

Tom Thomson was an influential Canadian artist and an expert canoeist who enjoyed many solo trips in Ontario’s Algonquin Park to fish, camp and paint. On 8 July 1917, the 39-year-old embarked across the park’s Canoe Lake. A few hours later, his canoe was found floating by the dock from which he had left. His body was found eight days later. There was a bruise on his head and fishing line wrapped around one of his ankles. A doctor concluded he had drowned. A day after having been discovered, Thomson’s body was buried in the small Mowat Cemetery near Canoe Lake.

There were questions regarding how such an experienced canoeist could have died in such a mysterious way, why the police had not done a more thorough investigation, and why, after two days, his body was exhumed and reinterred at the family plot in Leith, Ontario. In 1956, a skull was unearthed at the Canoe Lake site, and some argued that it was Thomson.

In 1970, William T. Little wrote The Tom Thomson Mystery, a book that detailed discrepancies in versions of Thomson’s death. In 1977, Roy MacGregor wrote in a Toronto Star article that Thomson was murdered by the Mowat Lodge’s owner, Shannon Fraser. MacGregor expanded upon his accusation in a 2010 book, Northern Light: The Enduring Mystery of Tom Thomson and the Woman Who Loved Him. He claimed that Fraser’s wife had told friends of her husband having killed the famous painter. The mystery came to the fore again with Gregory Klages’ 2016 book, The Many Deaths of Tom Thomson: Separating Fact from Fiction.

4. The Mystery of the Lost Lemon Mine

In 1870, prospector Frank Lemon and his partner, Blackjack, discovered a gold deposit by British Columbia’s Elk River, north of the Crowsnest Pass. That night, following an argument about the gold, Lemon murdered Blackjack by striking him in the head with an axe. Overwhelmed with regret, Lemon built a raging fire and later reported hearing moans and wails coming from the flames. The next morning, he walked to the nearest settlement, Tobacco Plains, and told Father Jean L’Heureax of the gold and murder.

Two Indigenous men had heard Lemon and Blackjack arguing and witnessed the murder. They told their chief, Joseph Bearspaw. Bearspaw knew that news of gold would bring people to the area and so declared that no one would speak of the murder or the gold.

Meanwhile, Father L’Heureax sent trapper John McDougall to bury Blackjack. He found the spot, buried Blackjack, and erected a modest cairn. Indigenous men destroyed it and hid evidence of its location. McDougall set out to lead others to the spot, but on the way, he drank himself to death. The priest organized an expedition to find the gold, but a forest fire had destroyed the route. Lemon tried several times to lead prospectors to the site but was always overcome with immobilizing fear. He eventually went mad.

American prospector Lafayette French, who had financed Lemon’s original expedition, tried to find the gold but contracted a debilitating illness and had to abandon his journey. French later found William Bendow, one of the men who had witnessed Blackjack’s murder. Bendow promised to lead French to the site, but he suddenly died from an unknown ailment. After 30 years of searching, French wrote to a friend to say he had finally found the Lemon gold. That night his cabin burned, and before he could reveal his secret, he died.

The Lost Lemon Mine: The Greatest Mystery of the Canadian Rockies (1958) by Dan Riley, Tom Primrose, and Hugh Dempsey, and The Lost Lemon Mine: An Unsolved Mystery of the Old West (2011) by Ron Stewart, have attempted to explain the mystery, but many questions remain unanswered.

5. Death on the Kettle Valley Line

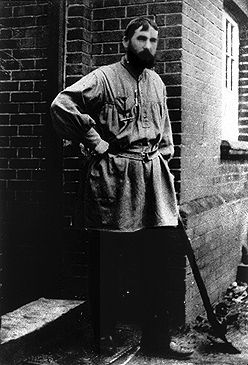

Among the thousands who settled the Canadian West in the 1890s were Doukhobors from Russia. Peter Vasilievich Verigin was the leader of the Doukhobors, a pacifist sect from Russia. Many of his followers believed him to be semidivine. (See also Russian Canadians.)

On 29 October 1924, the 65-year-old was travelling in a Canadian Pacific Railway car in British Columbia’s Kettle Valley when an explosion destroyed the train and killed him and all but two of his fellow passengers. An RCMP investigation was unable to conclude whether it was an accident or assassination.

Verigin’s son, Peter Petrovich, had threatened to kill his father during his 1905 visit to Canada. Suspicion fell on Peter Petrovich when, in 1927, he assumed the leadership of the Doukhobor sect in Canada. Groups within the Doukhobor community were also considered suspects. Independent Doukhobors wanted to pursue material wealth, while the Sons of Freedom wished to maintain traditional ways, and neither group thought Verigin represented their goals.

Others suspected the Russian government because at the end of the Russian Revolution, Russian officials asked the Doukhobors to return, but Verigin had refused. Meanwhile, many Western Canadians were suspicious of the Doukhobor culture, language and insularity, and someone motivated by nativist fear could have killed Verigin. The case remains unsolved.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom