National historic sites are places that are recognized for their importance in Canadian history. National historic sites are designated by the federal government, upon recommendation from an organization called the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada. In addition to sites, the board also designates people and events of national significance. These people and events are often commemorated by a plaque at a physical place. As of February 2020, there are 999 national historic sites in Canada. (See also Historic Sites in Canada; UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Canada).

Examples of National Historic Sites in Canada

There are national historic sites in every province and territory. In British Columbia, they include Kicking Horse Pass and Barkerville, and in Alberta Áísínai’pi (Writing-on-Stone) and Bar U Ranch. Saskatchewan is home to Batoche, as well as Fort Qu'Appelle. In Manitoba, national historic sites include Riel House, former home of Louis Riel and his family, and Lower Fort Garry. Ontario’s national historic sites include Queenston Heights and Maple Leaf Gardens, former home of the Toronto Maple Leafs. In Quebec, both Hochelaga and Château Frontenac are national historic sites. In the Maritimes, New Brunswick is home to the Saint John City Market National Historic Site (see Saint John) and Old Government House in Fredericton. Nova Scotia is home to the Springhill Coal Mining National Historic Site (see Springhill) and Prince Edward Island to Province House. L’Anse aux Meadows is a prominent national historic site in Newfoundland and Labrador. In Dawson, Yukon, a group of buildings in the city’s downtown comprise the Dawson Historical Complex National Historic Site. In the Northwest Territories, the site of two Christian missions within the Hay River reserve is a national historic site (see also Reserves in the Northwest Territories). Finally, the archaeological sites on Igloolik Island are one of the national historic sites found in Nunavut.

History

Development of Historic Site Commemoration Programs

At the end of the 19th century, interest in creating historic sites became fairly widespread in eastern Canada. This interest coincided with a rise of nationalist sentiment. Local patriotic and historical associations decided to preserve and mark places important to the historic identity of their particular regions. Some argued that their sites were also important to Canada’s history. They realized that historic sites could be popular tourist attractions, especially if they included picturesque ruins. In the late 1890s, Fort Lennox in Quebec became the first commercial historic park in Canada. It was operated by a private entrepreneur.

In 1907, following initiatives by Quebec organizations, the federal government created the Quebec (later National) Battlefields Commission. The commission was responsible for developing and preserving the site of the 1759 Battle of the Plains of Abraham. With no structures of the period to work with, the commission planned a landscape park with commemorative monuments.

Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada

The Saint John City Market is the oldest purpose-built market in Canada.

In 1919, the federal government established a program for the commemoration of places, persons and events of national historic significance. The Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada was created under the wing of the National Parks Branch (now Parks Canada). The board consisted of an appointed body of senior scholars and heritage experts. Their role was, and still is, to provide information and advice to the branch about sites, individuals and events worthy of commemoration. Subsequently most provincial governments appointed similar bodies to advise them on the creation of provincial historic sites. These programs generally focus on the designation of historic places, as opposed to events or persons.

Late 19th and Early 20th Centuries

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, sites were often chosen to commemorate important battles (e.g., Batoche, Crysler’s Farm), people (e.g., Pierre De la Vérendrye, Archibald Lampman, Alexander Macdonell), and political events such as the landing of United Empire loyalists in New Brunswick, or the first meeting of the executive council of Upper Canada. Sites associated with the fur trade (e.g., Cumberland House, Prince of Wales Fort, Fort Langley) were also commemorated in great numbers.

Until the 1930s efforts at developing historic sites were largely confined to interpretive plaques. If historic ruins were present they were usually left unimproved, with minimal effort made to prevent further deterioration. Early initiatives to preserve historic buildings included the transfer of a number of old forts formerly controlled by the Department of Militia and Defence to the National Parks Branch, which turned them into national historic parks. Some of these forts, such as Port-Royal and Fort Anne in Nova Scotia, did not stand any more and were replicated more or less faithfully. Other forts that were still relatively well preserved, such as Fort Chambly in Quebec, Prince of Wales Fort in Manitoba and Fort Henry in Ontario, were restored to their original state. In Quebec and Ontario local groups successfully preserved some important historical buildings. The Montréal Antiquarian and Numismatic Society acquired the Château de Ramezay for a museum building in 1895, and Toronto historical groups fought successfully to save old Fort York from destruction.

The success of large restoration projects in the United States and increased spending on public works during the Great Depression stimulated reconstruction and restoration initiatives in Canada. In the 1930s, the Niagara Parks Commission, an agency of the Ontario government, undertook four significant historic projects, two of which — Fort George at Niagara-on-the-Lake and Fort Erie — involved reconstructing nonexistent fortifications. Subsequently the provincial and federal government undertook the restoration of Fort Henry at Kingston.

Expansion of the National Historic Site Program

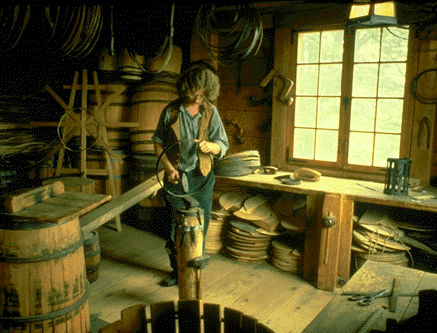

As they grew in age and maturity, historic sites programs broadened their horizons and diversified designations. In the 1950s, for instance, the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada (HSMBC) started to commemorate buildings based on their age or architectural value. Since then, built heritage — historic canals, railway stations, streetscapes, districts, gardens, and rural landscapes — has received growing attention. In 1961, Parks Canada undertook a large reconstruction project at the French fortress of Louisbourg, which was demolished by the British in 1758. The site was turned into an interpretive centre where costumed guides explain aspects of 18th century life at Louisbourg. In other locations, artificial pioneer communities (e.g., Kings Landing, Upper Canada Village) were created using historic buildings moved to the site. More recently, efforts have been directed at preserving buildings in their natural settings, retaining the original, or at least some practical function. Renovation and continuing maintenance are now favoured over reconstruction and restoration.

Also in the 1950s, the HSMBC began to commemorate places, persons and events related to the country's economy (e.g., Alexander Graham Bell, the Moose Factory building), and social history (e.g., the Grey Nuns’ Convent and Hospital, the Antigonish movement).

In the 1990s, Parks Canada identified three areas that were underrepresented among national historic sites. These were Indigenous peoples, women, and ethnocultural communities. Since then, efforts have been made to redress this imbalance. The recognition of Nagwichoonjik in the Northwest Territories, the Victorian Order of Nurses and the Abbotsford Sikh Temple in British Columbia are examples of these efforts (see Abbotsford; Sikhism in Canada).

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom