On 2 October 1758, Nova Scotia's first Legislative Assembly met in Halifax, and Canadian parliamentary government was born. The 22 members of the Assembly had been elected that summer by the votes of Protestant British males over 21 who owned property, a franchise that seems remarkably limited today, but was, in fact, liberal for that era.

It is important to reflect on what was achieved in Nova Scotia more than 250 years ago and what lessons we might take from this historical event in order to meet the challenges of democracy in our era.

There were three major turning points in the history of democracy: direct democracy, representative democracy and mass democracy. In their application to Canada, Maritimers, especially Nova Scotians, played a leading role.

Direct Democracy

Direct or participatory democracy was born in Athens in about 508 BCE. In that era of kings and empires, the Athenian idea that average citizens should decide policy rather than elites may be the single most revolutionary innovation in the history of government. Male citizens of Athens, about 30,000 out of a population of about 250,000 (slaves and women were not entitled to vote), had the right to attend 10 fixed meetings a year, where they deliberated on critical issues such as war and peace. Gathered on the Pnyx, a hill in Athens, citizens listened, debated and decided their fate.

Indigenous Forms of Democracy

Ever since then, Athens has been the model for participatory or strong democracy, where citizens play the deciding role in public affairs. But what is now Canada also has a tradition of participatory governance, one especially enshrined in the history of Indigenous peoples. There are over 600 First Nations communities in Canada today, and one should not make generalizations that apply to all. But the overarching procedures and principles of Indigenous governance stressed consensus and participation. The Haudenosaunee Confederacy’s Great Law of Peace (Kaianere'ko:wa), for example, acted as both a political constitution and a basis for Haudenosaunee society. Some believe the origin of the Confederacy goes as far back as the 12th century, although it certainly goes back at least to the mid-16th.

In Eastern Canada, several First Nations formed the Wabanaki Confederacy, and the Mi'kmaq had a sophisticated tri-level of leadership. Their villages had local chiefs and councils of elders; several villages came together in districts, presided over by a saqamaw (chief); and the seven districts formed a grand council, which was responsible for maintaining relations with other Indigenous nations and confederacies. Long before European settlement, Indigenous peoples had developed sophisticated mechanisms of government and international relations, and the basic principle of this system — consensus decision-making — is of continuing relevance to the modern age (see also Self-Government: Indigenous peoples and Territorial Government in Canada).

Representative Democracy

Direct democracy on the Athenian or Indigenous model had one major flaw: once you get beyond a certain size, it is not possible to put all your citizens atop a hill or around a campfire. The British solved the problem by a second great innovation — a representative Parliament. Citizens would not decide issues individually, as in Athens, but they would elect representatives to do so on their behalf (see Representative Government). The citizen assembly would evolve into a parliament of representatives. In 1265, Simon de Montfort convened a Parliament that contained two knights from the shires (i.e., counties), and two burgesses from each borough — one of a few examples of early representative parliaments.

This was the institution transplanted to Nova Scotia in 1758. As in Great Britain, the struggle in Nova Scotia soon became how to transform a representative legislature into a responsible government. Parliament's initial role in Great Britain was to ensure that the monarch heard the voices of the people, as he or she wielded the executive powers of government (see Crown). Britain had a mixed constitution comprised of an elected House of Commons, a hereditary House of Lords and a monarch. A mixed constitution was replicated in Nova Scotia and the other colonies of British North America. The appointed governor ruled with the assistance of an appointed Executive Council and an elected Legislative Assembly. The Assembly had the power to approve laws and withhold supplies, but the source of colonial power was in the governor, who was accountable to the imperial government in Great Britain.

As the Legislative Assembly was being inaugurated in Nova Scotia, however, the British Parliament was evolving toward a government dependent on the votes of a majority of the members of the House of Commons (see Government Power). King George III of Great Britain is as significant for grudgingly conceding power to the parties represented in Parliament as he is for losing the American Revolution. In the 1780s, the King was forced to accept a government that he detested (the Fox-North Coalition) because it commanded a majority in the House of Commons, and gradually the post of the prime minister began to supersede the power of the monarch.

The British debate over responsible government played out equally in Canada, with Nova Scotia leading the way. Nova Scotians began to demand that the members of the Executive Council, the forerunner to the Cabinet, should be responsible to the elected Assembly, not the appointed governor. In 1836, for example, Joseph Howe, the leader of the reform movement (the Liberals of the day), made the point that “all we ask for is what exists at home [Britain] — a system of responsibility to the people” (see Joseph Howe: Tribune of Nova Scotia).

In 1847, the Nova Scotia reformers won an election, and in January 1848, when the Conservative government was defeated following a vote of non-confidence in the Assembly, Lieutenant-Governor Sir John Harvey, called on James Boyle Uniacke, a reformer, to become the leader of the new government. “Nova Scotia,” writes historian W.S. MacNutt, “thus became the first province of British North America in which the system of responsible government was formally conceded and given effect.”

Mass Democracy and the Right to Vote

If direct democracy was the first turning point, and representative democracy and responsible government the second, mass democracy was the third milestone in democracy's evolution. If the people were to choose their representatives, who made up the people?

The initial answer in Nova Scotia in 1758 was Protestant men over 21 who owned property. But fairly quickly, Nova Scotia began to expand the franchise (those entitled to vote) and soon surpassed Great Britain in defining the boundaries of citizenship. In 1789, the Nova Scotia Assembly removed religious restrictions affecting the right to vote (Roman Catholics in Great Britain had to wait until 1829 to enjoy the franchise). In 1854, Nova Scotia introduced a broader male suffrage, increasing the number of electors by 50 per cent, the first jurisdiction in North America to do so. New Brunswick also innovated, introducing the secret ballot in 1855, a reform not adopted in Canada proper until 1874. This measure was crucial for reducing election violence. With public voting, gangs could intimidate and violently block their opponents. Robert Baldwin, the great Upper Canadian reformer, once had to flee a mob or Orange Order thugs at the polls. Before Confederation, there were 20 deaths due to election violence, but the secret ballot and simultaneous voting (as opposed to staggered dates) ended the reign of electoral terror (see Elections).

Women’s Right to Vote

Subject to the civil code rather than the common law, women in Lower Canada (Québec) who owned property could vote on the same basis as men in 1791. Though there is evidence that women occasionally voted in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, for a time, Québec was a leader in gender equality. But the Act of Union — which united Upper and Lower Canada — expressly prohibited women from voting in 1849, ending women’s right to vote in Québec for over 90 years. Most women, however, had to wait until 1918 before they were considered as citizens entitled to vote federally, while Asian and Indigenous women could not vote until 1948 and 1960, respectively. Nova Scotia gave women the provincial right to vote in 1918 (see Women’s Suffrage in Canada).

Legacy

Each of the three turning points — direct democracy, representative democracy and mass democracy — continue to be issues for us today. Many citizens yearn to have a direct impact on policy, rather than pleading with a bureaucrat or visiting the constituency office of a member of Parliament (MP). Some suggest that online voting might be a technique that could replicate, in Canada, the direct democracy of the Pnyx in Athens. But how many citizens would engage in the process as opposed to special-interest groups? The Indigenous tradition of consensus equally depends on extensive discussion and mutual learning. But how many citizens have the time to engage so intensively? Randomly selected citizen panels might be one answer. They have already been used to advise governments on electoral systems and, in the United Kingdom, they have been employed on broader issues such as city planning. But this democratic innovation depends on volunteers willing to spend their weekends discussing policy.

The representative institution of Parliament also is badly in need of reform. Partisan wrangling has reduced question period to a reality-show circus, and many MPs feel that they have little influence on the executive (see Parliamentary Procedure). The origins of Parliament in 1265 were intended to provide some restraint on the power of the executive; how to rebalance power between the prime minister and Parliament today is as necessary as it was once to balance the power of the king.

Significance

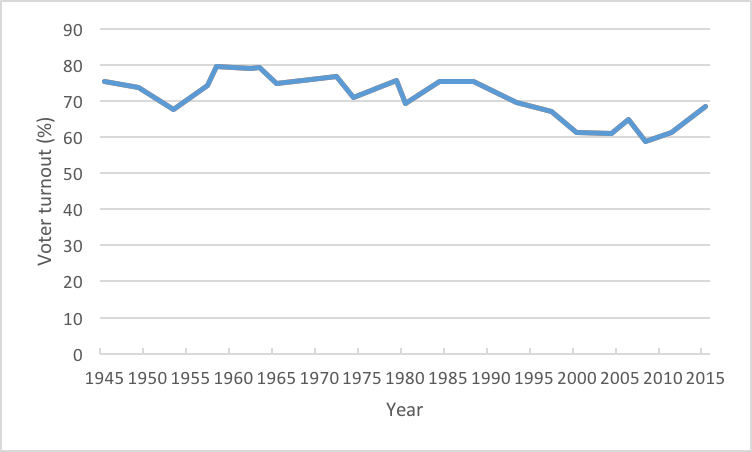

Canada's mass democracy is losing its mass. In Nova Scotia's first election, in July 1758, Lunenburg township had 70 eligible voters, 58 of whom voted for 2 members from a list of 7 candidates. That reflects an 82 per cent voter turnout (see Electoral Behaviour). The percentage of voter turnout to federal elections in the first decade of the 21st century was roughly 60 per cent, and according to Elections Canada, the lowest turnout was from young voters (aged 18–24), averaging about 40 per cent, compared with roughly 74 per cent of voters aged 65–74.

We know that turnout is related to the amount of confidence individuals have in their knowledge of a subject. The calamitous decline in the teaching of Canadian history in our school systems may be a contributing factor in the low percentage of young people voting. If one does not know about the origins of Parliament, why vote for a member of Parliament?

Democracy is always a work in progress. Issues change, and intuitions evolve. Canadian democracy is certainly in need of major repair: voting turnout is mediocre, parliamentary accountability is in decline and citizens are frustrated in their ability to contribute to decisions that influence their lives (see Electoral Reform). We must retain the optimism of Joseph Howe, the greatest of Nova Scotia reformers. He told the electors of Nova Scotia in 1851 that even after the great achievement of responsible government, the reform agenda was not done. Howe wrote, “a noble heart is beating beneath the giant ribs of North America now. See that you do not, by apathy or indifference, depress its healthy pulsations.”

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom