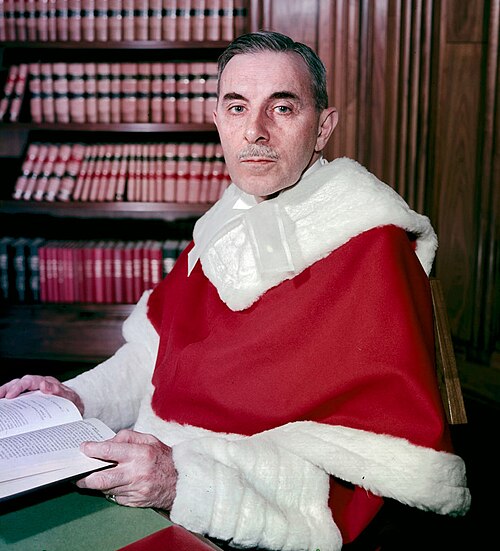

Patrick Greatcourt Kerwin, PC, chief justice of Canada 1954–63, Supreme Court of Canada justice 1935–54, lawyer (born 25 October 1889 in Sarnia, ON; died 2 February 1963 in Ottawa, ON). Patrick Kerwin worked as a lawyer in Guelph, Ontario, for 21 years. He also served as the solicitor for the city and for Wellington County and was one of the county’s Crown attorneys. In 1932, he became the youngest person appointed to the High Court Division of Ontario’s Supreme Court (now the Ontario Superior Court of Justice). As a justice of the Supreme Court of Canada, Kerwin upheld the unwritten constitutional principle that no public official is above the law. As the chief justice of Canada, he contributed to the growing legal and constitutional recognition of civil liberties and freedom of expression.

Early Life and Education

Patrick Kerwin was born and raised in Sarnia, Ontario. His father, Patrick, was a Great Lakes ship captain and then a liquor store owner. He died when Kerwin was eight years old. His mother, Ellen (née Gavin), moved Kerwin and his younger brother and sister to her parents’ home, where he grew up. He worked part-time as a musician and for a butcher shop while attending Sarnia Collegiate Institute.

Showing an interest in the law, Kerwin worked as an office clerk. During his high school years, he worked as a clerk with the local law firm of Hanna, McCarthy and LeSueur. Following his graduation, he clerked at the firm of Hanna, LaSeuer & Price. In 1908, because university education was not needed to attend law school at the time, Kerwin moved to Toronto to attend Osgoode Hall Law School. In 1911, he graduated and was admitted to the bar.

Early Career

When he was 21, Patrick Kerwin joined the father-and-son law firm of Guthrie and Guthrie in Guelph, Ontario. Two years later, he became a partner in Guthrie, Guthrie and Kerwin. On 2 June 1914, Kerwin married Georgina Mace. They had four children: Isobel, Philip, George and Patrick.

With Donald Guthrie’s death in 1915, the firm became Guthrie and Kerwin. When Hugh Guthrie entered politics, Kerwin became the firm’s senior partner and then its head. He handled many different cases during his 21 years in Guelph. He also served as the solicitor for the city and Wellington County and was one of the county’s Crown attorneys.

Early Career as Judge

In 1932, at age 42, Patrick Kerwin became the youngest person ever appointed to the High Court Division of Ontario’s Supreme Court (now the Ontario Superior Court of Justice). For three years, he adjudicated many civil, criminal and family law cases.

On 20 July 1935, Prime Minister R.B. Bennett appointed Kerwin to serve as a justice on the Supreme Court of Canada. He served on the court for 27 years and learned French so he could hear cases in both languages.

Among the most significant cases Kerwin addressed was Nobel et al v. Alley. It began in 1933 when Annie Noble purchased land in Ontario. A restrictive covenant on the deed stated: “the lands therein described should never be sold to any person of the Jewish, Hebrew, Semitic, Negro or coloured race or blood.” In 1948, Noble sought to sell the property to Bernard Wolf, who was Jewish, but a local property owner’s association claimed the sale violated the covenant. When the case went to the province’s Superior Court, Kerwin was among the justices whose arguments ruled in favour of Noble and Wolf. The decision brought into question the legal status of any existing property agreements that were discriminatory. It led to several provinces outlawing these practices in the early 1950s.

Chief Justice of Canada

On 1 July 1954, Prime Minister Louis St-Laurent appointed Patrick Kerwin chief justice of the Supreme Court of Canada. In doing so, he ignored those who argued that Kerwin’s Catholicism should be disqualifying because the previous chief justice, Thibaudeau Rinfret, was also Catholic.

The Kerwin Court oversaw many significant cases. Among them was Roncarelli v. Duplessis. Quebec premier and attorney general Maurice Duplessis had strong ties to the Catholic Church. Restaurant owner and Jehovah’s Witness Frank Roncarelli provided bail to 390 people of his religion whom Duplessis had arrested for publicizing Jehovah’s Witness beliefs. Roncarelli claimed that the premier had revoked his liquor licence in retaliation for his actions. In 1959, the Kerwin Court ruled in favour of Roncarelli and upheld Roncarelli’s suit for damages against the premier. The decision upheld the unwritten constitutional principle that no public official is above the law.

A 1960 case, The Queen v. George, involved a man who had been acquitted by a lower court because he had been so intoxicated that he could not form criminal intent when he committed robbery and assault. The case went to the definition of mens rea; that is, whether a person’s intention to commit a crime matters in determining whether they can be found guilty of committing that crime. The Court advanced the definition of mens rea when it found that intoxication is a legally valid defence to crimes that involve a specific intent to benefit, such as robbery, but not to crimes of a more general intent that were not done to obtain a benefit, such as assault or drunk driving.

Another important case began in 1937 when the Quebec government passed the Padlock Act. It enabled the closing of any building that housed meetings of communists. In 1957, the law’s constitutionality came to the Supreme Court with Switzman v. Elbling and A.G. of Quebec. Kerwin’s Court ended the Padlock Law, finding it beyond the constitutional jurisdiction of a provincial government. The case contributed to the growing legal and constitutional recognition of civil liberties and freedom of expression.

Death

Patrick Kerwin died in Ottawa on 2 February 1963 at the age of 73. He is the only chief justice of Canada to die while in office. Governor General Georges Vanier eulogized Kerwin, describing his service as reflecting grace and wisdom.

(See also Judiciary in Canada; Court System of Canada.)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom