The Persons Case was a constitutional ruling. It established the right of women to serve in the Senate. The case was started by the Famous Five. They were a group of women activists. In 1928, they objected to a Supreme Court of Canada ruling that women were not “persons.” As such, they were not allowed to serve in the Senate. The Famous Five challenged the law. In 1929, the decision was reversed. As a result, women were legally recognized as “persons.” They could no longer be denied rights based on a narrow reading of the law.

(This article is a plain-language summary of the Persons Case. If you are interested in reading about this topic in more depth, please see the full-length entry.)

Background

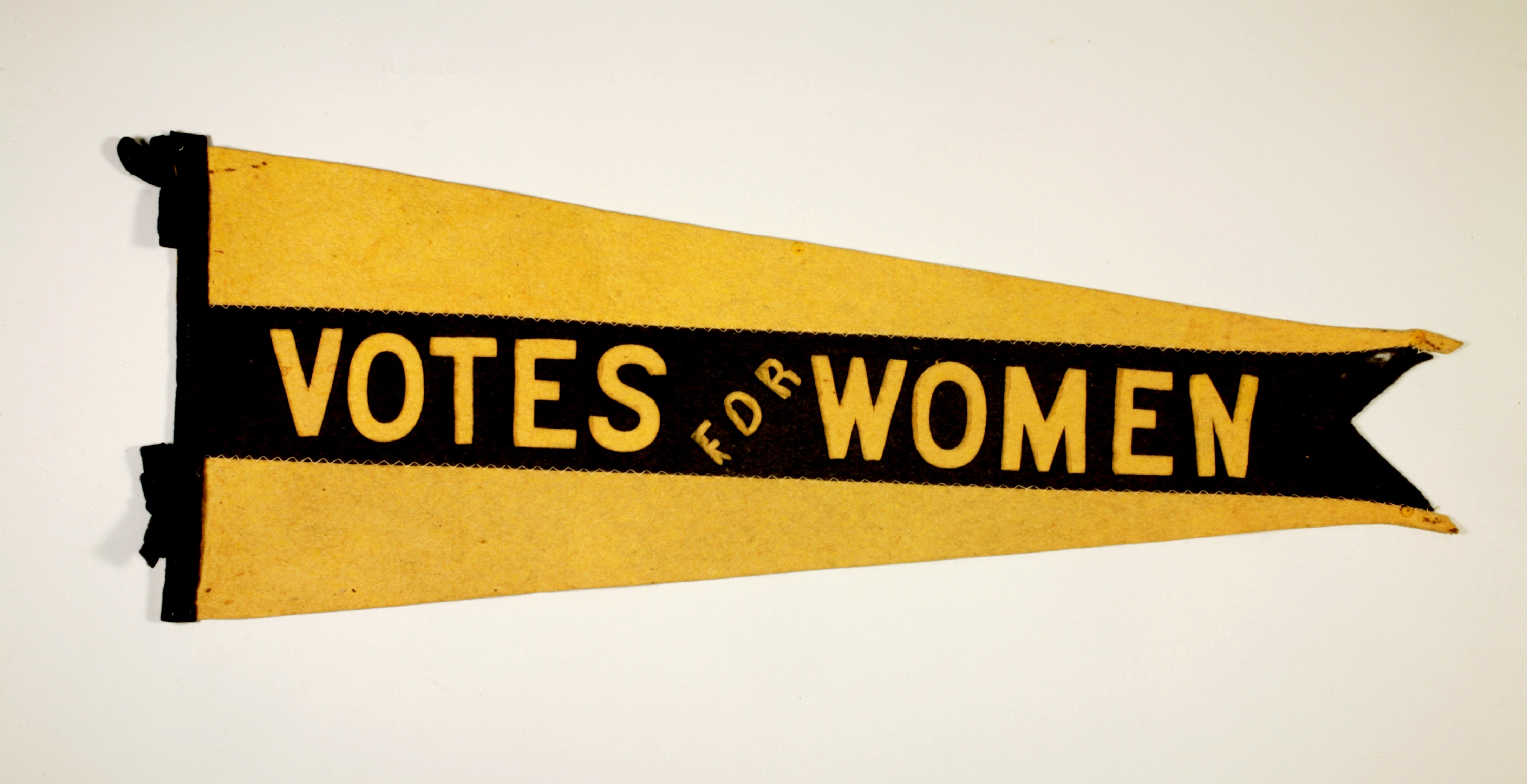

Manitoba first granted women the right to vote and to hold political office in January 1916. In May 1918, most Canadian women over the age of 21 could vote in federal elections. By 1927, most Canadian women could vote and run as candidates in federal and provincial elections.

In 1919, women received the right to run for office in the House of Commons. But the Senate was still closed to them. This was because of the way the federal government interpreted section 24 of the British North America Act (BNA Act). It is now known as the Constitution Act, 1867. It is the law that created and governed Canada.

According to section 24 of the Act, only “qualified persons” could be appointed to the Senate. To be a “qualified person” was to be at least 30 years old; own property worth at least $4,000; and reside in the province of their appointment. But the Act did not specify whether “persons” included women. In 1867, when the Act was written, “person” legally referred only to men. As a result, the government saw “persons” as being men only.

In 1922, female activists proposed Emily Murphy, Canada’s first woman judge, for a Senate position. Many newspapers and women’s groups championed her cause. But the government said that “the British North America Act made no provision for women.”

The Famous Five Petition

On 27 August 1927, Emily Murphy, Nellie McClung, Irene Parlby, Louise McKinney and Henrietta Muir Edwards sent a petition to the governor general. They did so under section 60 of the Supreme Court Act. It allows a group of five persons to ask that the Supreme Court interpret a point of law in the BNA Act. The petition asked the Court to rule on two questions:

- Does the governor general or Parliament have the power to appoint a female to the Senate?

- Is it constitutionally possible for Parliament to allow a female to be appointed to the Senate?

The Supreme Court was then asked to answer whether “person” in section 24 of the BNA Act included female persons.

Supreme Court Decision

On 24 April 1928, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled unanimously that women were not “persons” under section 24 of the BNA Act. The decision was based on the premise that the BNA Act had to be read the same way in 1928 as in 1867. The justices said that the BNA Act would have specifically referred to women if it had meant for them to be included.

Privy Council Decision

There was one higher authority to which the Famous Five could appeal. At the time, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council was Canada’s highest court of appeal. On 18 October 1929, the Privy Council reversed the decision of the Supreme Court. It concluded that “the word ‘persons’ in sec. 24 does include women.” It also found that women are eligible to become members of the Senate.

Legacy

The Persons Case was a significant milestone in the history of women’s rights. The decision legally recognized women as “persons.” Women could no longer be denied rights based on narrow readings of the law. Women could continue to work for greater rights through both the Senate and the House of Commons. On 15 February 1930, Cairine Wilson was sworn in as Canada’s first female senator.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom