Peter Maloney, lawyer, entrepreneur, politician, advocate (born 1944 or 1945 in Toronto, ON). Peter Maloney is recognized as the first openly gay political figure in Canada. He made unsuccessful bids for the Ontario legislature in 1971 and for the Toronto School Board in 1972. He came out at a Liberal Party convention in February 1972. He later became a successful bathhouse owner and was described by Toronto Life magazine in 1976 as “Canada’s first acknowledged gay millionaire.” Several police raids on bathhouses in the late 1970s and early 1980s thrust Maloney back into the legal and political spotlight. In 1980, he led a group arguing that the Charter of Rights and Freedoms should protect people from discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation.

Early Career

Peter Maloney grew up in Montreal. He became involved with the Liberal Party after Pierre Trudeau’s government decriminalized homosexuality in 1969. In 1970, he moved to Toronto to work as an economist at the Toronto Stock Exchange. The following year, he ran for provincial parliament. He lost to Progressive Conservative incumbent and attorney general Allan Lawrence. He had attempted to undermine Maloney by privately disclosing his homosexuality to the press.

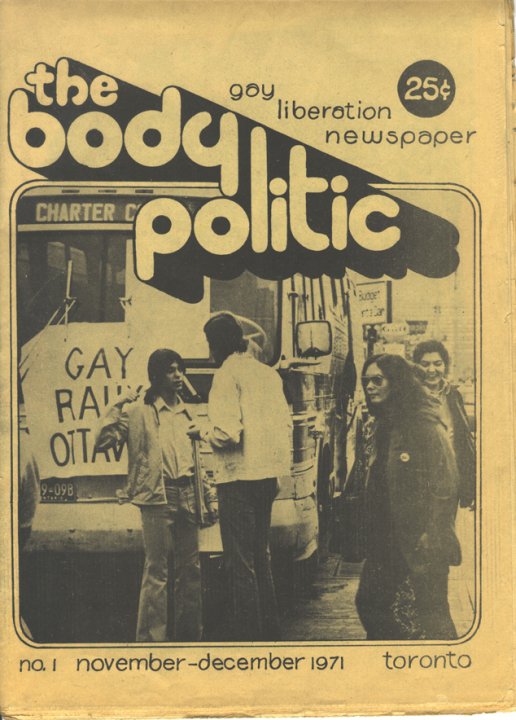

Maloney maintained an active, if critical, relationship with the Liberal establishment following his loss. At a policy convention in Ottawa in February 1972, he came out as gay and publicly lambasted members of the federal cabinet for barring gay people from immigrating to Canada.

His bid for office had personal consequences as well. Maloney had run a conventional campaign but without significant financial backing. He ultimately financed much of the campaign himself and sunk deep into debt in the process. Despite this, he ran for a seat on the Toronto School Board in 1972 in response to a petition to bar gay activists from speaking to high school students. His bid was again unsuccessful.

Bathhouse Business Owner

Seeking to recuperate his financial losses, Peter Maloney went into business with an American firm, Club Baths, to establish a new bathhouse in Toronto. It attracted a large clientele. Maloney soon opened other locations in Ottawa and Montreal. In 1974, he and George Hislop opened another Toronto business called The Barracks. It catered to sadomasochist patrons and included a shop for dildos, whips, chains and other sex toys.

These ventures significantly reversed Maloney’s fortunes. A 1976 Toronto Life story described Maloney as “Canada’s first acknowledged gay millionaire.” But the bathhouses also carried significant risks. Following the decriminalization of homosexuality, gay bathhouse culture had flourished in Canada’s major cities. But police were nonetheless empowered to prosecute “indecent acts.” Combined, these two factors made the late 1970s and early 1980s a period of frequent bathhouse raids. (See Toronto Bathhouse Raids, 1981; Sex Garage Raid.)

The violence was met with protests in the gay community. This put Maloney at the centre of some of the most tumultuous events in the struggle for gay liberation in Canada. Club Baths in Montreal was raided in January of 1976 and again in May, when the City of Montreal was attempting to force all “visible” gay business activity underground ahead of the Montreal Olympics. Club Baths of Ottawa was also raided in May 1976. Maloney was charged with keeping a “bawdy house.” He and his supporters argued that the charges were baseless given that activities at the bathhouses had been decriminalized. But he nonetheless pleaded guilty and was fined $500.

After The Barracks was raided in December 1978, Maloney began a fund to cover the legal costs of the men who had been charged. That project would transform into the Right to Privacy Committee. It became a central advocacy group, especially following the sweeping bathhouse raids of 1981. Maloney was charged again in these raids. But he defended himself and others successfully. The charges were dropped after Maloney agreed that he would not sue the police for malicious prosecution.

Police Critic

In addition to these legal battles, Maloney began openly criticizing the Toronto Police Service for what he viewed as a lack of accountability. “I was constantly going after the police budget,” he later said in interview. “How much were they spending? Why were they getting increases? Why did they need any new officers, et cetera, et cetera?”

These activities aggravated the police to the extent that they began spying on Maloney, pressuring his postal officer into reporting on his correspondents. They did so again a decade later. In 1991, Maloney’s friend Susan Eng became chair of the Toronto Police Services Board, which oversees police operations. Records later revealed that Toronto police were illegally spying on both Maloney and Eng by taping their phone calls. The police claimed this was because they suspected Maloney of dealing drugs, though they never presented any evidence of this.

Return to Politics

Even as Peter Maloney antagonized the political establishment, he was more closely connected to it than most in the gay community. In the late 1970s, he went to law school. (He needed special permission from the Law Society to article despite his 1976 conviction).

Maloney also maintained his ties to the Liberal Party, serving as vice president of the Toronto and District Liberal Association. In 1980, he led a delegation of members from the Canadian Association of Lesbians and Gay Men to Ottawa. They argued that the Charter of Rights and Freedoms should protect Canadians from discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. He also made another attempt at provincial office in 1981 but was criticized as a single-issue candidate and did not get on the ticket. In 1991, he ran for a seat on Toronto City Council but lost to Kyle Rae, who became Toronto’s first openly gay councillor.

Maloney eventually moved to Kitchener, Ontario. He chaired the Kitchener South-Hespeler Federal Liberal Riding Association.

Legacy

Like other identity-based anti-oppression movements, gay liberation was often divided internally “between radical ‘liberationists’ and liberal ‘assimilationists’,” as Tim McCaskell has written. Peter Maloney was decisively part of the second camp. He sometimes butted heads with others in the community, who were pessimistic about legislative change or cultural acceptance by mainstream Canadian society. Yet as both camps pushed for — and won — progressive victories, that division abated over time.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom