Military Role (1660–1816)

Quebec’s history is inseparable from that of the St. Lawrence River. At the beginning of the French regime, the colony was very isolated, so much so that the river was the only link with Metropolitan France. It brought colonists, trade and prosperity, but also the threat of invasion. From the outset, the layout of the port reflected these concerns.

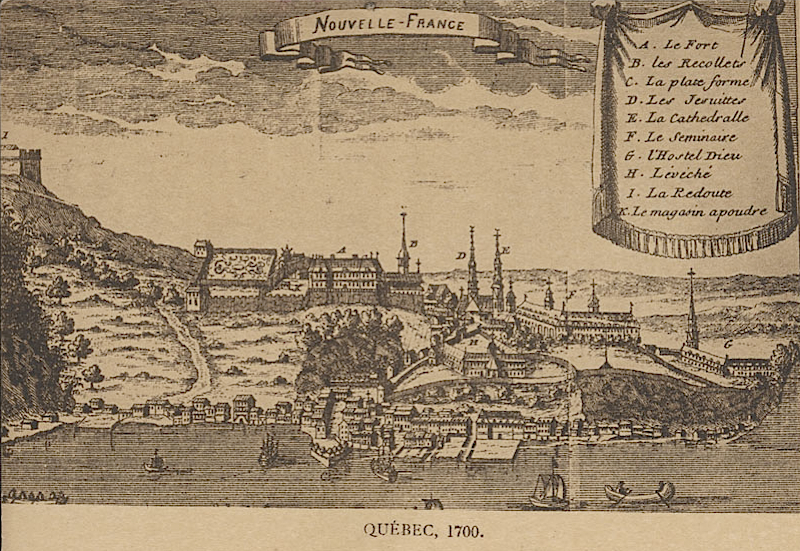

The town’s location was chosen in particular for its maritime qualities: the large basin could accommodate more than one hundred ships annually, and the narrowness of the river at that point made it easier to control navigation. In the beginning, the port’s facilities were rudimentary. Towards the end of the 17th century, the first concessions were established along Quebec’s shoreline, where the shoreline landowners first built cedar post fencing.

But Quebec was a military town, and this was reflected early on in the port’s appearance, particularly with the construction of two cannon platforms in 1660 and 1690 at Pointe aux Roches, where the royal battery was also constructed in 1691 following an attack on the town by William Phips.

The harbourfront grew over the course of the 18th century, and two other batteries were installed on private wharves: the Dauphine battery in 1709 and the Pointe à Carcy battery during the . The port took on a rectilinear shape, with a small cove in the west, the Cul-de-Sac, where a shipyard was developed between 1746 and 1748. Repeated attacks by the English in 1690 and 1759 justified this military role.

After the Conquest, transatlantic trade routes shifted towards England. The port began to transform radically, taking on a more commercial role. The batteries were disarmed, and part of the river was filled in to construct warehouses and marketplaces. The French’s rectilinear harbourfront grew jagged during the British period, with the construction of deepwater ports favoured by the English.

Commercial Role (1816–1880)

In the first half of the 19th century, the Port of Quebec grew dramatically. Following the example of John Goudie, new merchants’ wharves comprising a jetty stretching out into the river were built in 1816 and were among the first of their kind. Goudie also undertook the construction and commissioning of the Lauzon, the first steamship ferry linking Quebec and Pointe-Lévy, in 1817. Starting in 1854, the Grand Trunk railway terminal at Pointe-Lévy also served Quebec, significantly improving the mobility of goods from the port.

Rapid development of facilities was prompted by importers and exporters of a variety of goods: , pork, beef, sugar, rum and especially (see also Imports, Exports). Quebec was a prosperous town that attracted merchants wanting to profit from this prosperity by having their own wharves built.

The development of the Saint-Roch neighbourhood into the 1840s gave rise to new jetties at the mouth of the Saint-Charles River. This waterway provided a safe harbour and direct access to the St. Lawrence. In the first quarter of the 19th century, approximately 20 shipyards along the Saint-Charles employed roughly 3,000 workers.

From 1760 to 1825, the shipyards of Quebec and the surrounding area produced approximately 38 per cent of the vessels built in Lower Canada. To the west, the wharves stretched all the way to Anse-au-Foulon, the whole area of which formed an immense floating warehouse where lumber from the Ottawa River ended up (see Timber Trade History).

The Burnett and Olivier jetties marked the northern boundary of the port. It was there that the customs building (see Customs and Excise) and the commissioner’s wharf were constructed in the mid-19th century. These structures would be central to the other major purpose of the port, which would have a lasting effect on its appearance — immigration.

Timber Trade

Starting in the early 19th century, squared timber was assembled into cribs, which in turn were assembled into drams that floated naturally on the current down the St. Lawrence during the thaw. Small crews of workers known as raftsmen or log drivers manoeuvred the drams on a voyage that lasted about a month. Several drams formed a the first of which to arrive in Quebec was the Colombo in 1806. The timber was then stored in ships that, once their holds were fully stocked, made their way to England with their heavy cargo. Because of this trade, in the mid-19th century the Port of Quebec became one of the largest ports in North America. During these golden years, around 1845, the value of lumber exports surpassed one million pounds. This new state of affairs resulted from Napoleon’s continental blockade of the British Isles from 1806 (see Napoleonic Wars), preventing the English from receiving supplies from continental Europe and forcing them to turn to Canada for pine and oak.

Immigration Port

Once the timber had been unloaded at English ports, the captains would often try to make their return journeys profitable by taking advantage of immigrants’ desire to make the long crossing to the New World. The same unsanitary holds used to transport timber were thus filled with passengers. These impromptu crossings frequently took place under deplorable and dangerous conditions, so much so that the ships became breeding grounds for disease. Cholera in the 1830s, then a form of typhus commonly known as “ship fever” developed rapidly in these environments and wreaked havoc in Quebec as well as in Montreal, Bytown (Ottawa) and Toronto, particularly during the summer of 1847 (see Epidemic). To reduce the impact of disease, a quarantine area was created on Grosse Île in 1832 and remained in operation until 1937.

Canada’s prosperity attracted people from Europe and the British Isles, whose arrival required changes to be made to the port facilities. The bustling commercial jetties were unsuitable for receiving newcomers with heavy luggage.

From 1815 to 1851, the Port of Quebec registered over 800,000 British and Irish immigrants. An average of 26,000 people per year took this required step to enter North America. The town’s infrastructure had to adapt to this new reality.

In the last quarter of the 19th century, Quebec’s port economy began to stall. Montreal’s emergence as a rival economic hub, the end of preferential tariffs with England and the construction of ships made of iron, and later steel, caused lumber exports and shipbuilding to plummet to such an extent that they all but disappeared. However, immigration continued; redeveloping the port was inevitable.

Necessary Redevelopment (1882–1960)

Renovating the facility into a large modern port was so vital to Quebec’s economic recovery that even Queen Victoria officially endorsed it. The site was to have immense buildings, jetties and docks that would make Quebec a competitive port. The project became known as the Louise Basin, in tribute to Princess Louise, daughter of the British monarch and wife of the Governor General of Canada, who symbolically laid its cornerstone.

Two basins separated by a lock aimed to protect ships from tidal variations. Large transatlantic ships anchored on the north side of the jetty. The entire site was connected to the railway network, around which hangars, service buildings and storage facilities were eventually located.

Started in 1877 and completed in 1882, the Louise Basin building was also the new gateway for immigrants. To meet these needs, a large two-storey structure was erected on the Louise jetty in 1888. The “immigrant building” could accommodate 4,000 people and featured dormitories, a dining room, an exchange office, stores, an immigration office and a medical office, as well as new telegraph technology. From there, newcomers could directly board a train that would transport them to their new lives. These facilities served as the gateway to Canada for generations of immigrants.

Marina (1960 to Present)

In 1920, the construction of enormous grain silos — which dominate the city’s port landscape even today — contributed to shifting the port’s activities towards the agricultural industry (see Grain Handling and Marketing). From the 1960s to the 2000s, the port broke a number of records in terms of the volume of goods that passed through Quebec, peaking at 33 million tonnes in 2012.

Over time, the spaces between wharves were filled in to serve two new purposes that would also shape the port: tourism and cruise lines. In 1991, cruises officially launched in Quebec, during a decade in which port operations saw a slump in the trade of grain products. This new tourist market continued to grow rapidly. In 2017, the port welcomed over 200,000 visitors for the first time, making tourism one of its major activities.

In a surprising twist of fate, the Port of Quebec has now reverted to the straight shape parallel to the river that it once had during the French regime, as if echoes of history continue to affect its appearance, blending together the eras to meet its evolving needs.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom