Prison Architecture

Prison architecture reflects society's changing attitudes toward crime and punishment. Prisons have evolved from simple places for incarceration (where protection of the public is paramount) to instruments of punishment (where deprivation of liberty is the penalty for breaking the law), to settings for reform (where attempts are made to mould the guilty to conform with society's norms).

Prisons for Short-Term Detention

Throughout the French regime and in the early decades of British rule, imprisonment was a means of detaining debtors to ensure payment, the accused before trial, or the guilty before punishment. Courts, following English and French practice, imposed sentences including fines, personal mutilation such as flogging or branding, and death. In 18th-century England, transportation to penal settlements in the thirteen colonies (and, after American independence, Australia) became an increasingly popular penalty because it removed the guilty from local society; length of sentence and destination reflected the severity with which the court viewed the offence.

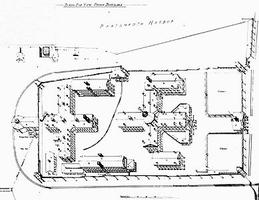

Before 1800, prisons in the North American colonies, like those in the motherlands, were used for short-term detention. Often placed in existing facilities such as military works, which offered appropriate levels of security, pre-1800 prisons usually consisted of large open rooms where inmates lived communally in unsupervised and unsanitary conditions.

Strong-box jails, whose purpose was primarily the secure holding of individual prisoners, were designed into the 19th century, mainly to serve municipalities. An early example, at Trois-Rivières, Québec (1822), is a national historic site whose classical Palladian appearance is belied by the iron bars on the windows that announce its function.

The Penitentiary

After the passing of Britain's 1779 Penitentiary Act, which made imprisonment an alternative to traditional sentences, a new type of prison emerged — the penitentiary. Buildings were designed to be supervised by paid staff. These institutions had to accommodate labour programs (which taught work habits and helped to maintain the institution), the classification of inmates by sex, age and level of criminality, and the principle of individual cellular confinement (one inmate per cell). It was expected that penitentiaries would act as deterrents to crime.

The principles behind penitentiaries, promoted by late 18th-century English prison reformers under the leadership of the High Sheriff of Bedfordshire, John Howard, affected British prison architecture for 150 years and began to affect Canadian design early in the 19th century. François Baillairgé's (see Baillairgé family) plan for the prison at Québec City (opened 1809) was dominated by communal living spaces but offered some individual cells and a measure of classification by sex and type of crime. The city prison in Montréal, planned in 1826 by George Blaiklock and erected along more modern lines in 1832–36 (John WELLS, architect), was a transitional structure that contained both single and double cells along with communal day rooms, chapels and dining halls. The only classification was between male and female inmates.

Effects of American Reformer Philosophy on Prison Design

Howard-inspired prison reformers sought to add reform to punishment and deterrence as a principle of prison design. Believing that criminality was caused by a lack of moral values and social structure in an individual's life, advocates of reformatory prisons argued that a regimen of silence, isolation, religious training and hard labour could force the inmate to self-examination, an awareness of the cost of criminality, and the importance of approved social values and work habits.

In the early decades of the 19th century, American social commentators in New York and Pennsylvania devised two architectural formulas to support the reform principle. The Auburn approach employed cellblocks consisting of rows of very small cells placed back-to-back in the centre of the building and separate large workshops where inmates laboured together. The Pennsylvania system advocated cellblocks laid out in a radial pattern from a principal supervisory station, each block consisting of a central corridor flanked by rows of comparatively large cells where inmates lived and worked for their entire sentences. The effectiveness of the Auburn approach depended on a regime of brutal punishments for breaches of regulations, especially the rule of silence, and therefore required a large staff. Its communal labour programs permitted a broad range of potentially profitable industrial activities. The method and form of Pennsylvania-styled prisons led to smaller staffs but a very narrow range of labour programs.

Kingston Penitentiary and the Auburn Approach

The belief that prison design could reform inmates influenced the planning and design of the provincial penitentiary in Kingston (opened to its firstinmates on 1 June 1835). Designed by the former deputy warden of the New York state prison at Auburn, William Powers, and built under that institution's master builder, John Mills, Kingston Penitentiary was an exceptionally faithful illustration of the Auburn correctional philosophy. Planned to house 880 prisoners (and therefore ranking among the institutions with the greatest capacity in the world; the largest, England's Millbank prison, housed 1,000), it consists of a grand entry gateway, in the form of a triumphal arch, leading to an enormous cross-shaped main cellblock (reportedly the largest non-military structure in Canada at the time), and an equally huge cross-shaped workshop behind, all placed within a ten-acre walled enclosure. The cellblock housed administrative facilities (offices, a staff room, a library, and housing for the warden and deputy warden) in the front wing and inmate accommodations in the other three. An impressive domed rotunda linked the four pavilions.

Inmates at Kingston spent their nonworking hours in tiny cells, each measuring 2 m by 0.6 m (6 feet by 2 feet) in size, and each separated from the neighbouring unit by 2-foot-thick stone walls that effectively prevented inmate communications that might lead to further moral contamination. These cells, fronted by thick wooden doors which were pierced by small barred openings for ventilation and supervision, were laid out in long rows stacked five cells high in the middle of the cellblock. This plan was designed to permit continuous staff supervision of each cell from both the front and rear. Religious instruction (which originally took place with the inmates locked in their cells) and the regime of total silence ensured that the prisoners’ minds would be focused on the consequences of evil. Labour programs, designed to reform the inmates and to support the institution financially, were carried out in large open workshops that were easily supervised. Inmate labour was sold to entrepreneurs who transformed the prison workshops into factories that produced furniture, metal goods, and shoes and other leather products. Work was to inculcate socially acceptable habits and attitudes that, combined with moral instruction supported by extraordinarily harsh discipline, would ensure that criminals had every possible incentive to reform themselves.

The Effectiveness of the Auburn Model Questioned

The high number of repeat offenders and an 1846 inquiry into the operation of Kingston Penitentiary suggested that the Auburn system had proven ineffective in reforming inmates. The 1846 inquiry had also raised a serious issue: the imprisonment of juvenile offenders — some as young as ten years of age — in institutions designed for adults. The first attempt to resolve the issue was the design of a reform school, initially located in the fort at Île-aux-Noix, Québec, which was opened in 1857. This institution inspired a series of correctional facilities for young delinquents, including industrial schools, which the government of Québec authorized as early as 1869. Providing for the distinctive needs of young offenders led authorities to abandon their traditional dependence on labour and the cell and develop an approach that blended the design of contemporary public schools and orphanages.

Despite questions about its effectiveness, the Auburn model used at Kingston Penitentiary prevailed as the norm until the 1930s. Its cellblock layout — cells laid out in long rows stacked in the centre of wings placed behind an administrative pavilion, the whole surrounded by imposing stone walls — was copied for penal institutions at all levels. Most fully developed at provincial institutions such as the one at Kingston or, on a smaller scale, at Halifax , the Auburn model was gradually adopted in the planning of municipal jails. A pioneer in this regard was the jail built by the city of Saint John, New Brunswick, in 1839, which used the Auburn layout of cells and inspection corridors in its single cellblock but provided no religious training or labour programs.

By the 1850s and 1860s, the Kingston layout of a central administration building with wings of Auburn-styled cells was used in the planning of city jails in centres such as St John's (1859), Toronto (the Don Jail of 1858-64, designed by William THOMAS), Ottawa (1860-62, designed by Horsey and Sheard), and Québec City (1862-65, designed by Charles Baillairgé). When provincial authorities ordered new jails constructed in the county capitals throughout Upper and Lower Canada in the 1850s and 1860s, they were also invariably simplified versions of the Kingston model — fronting administration pavilions (sometimes joined to courthouses) leading to one or more cellblock wings consisting of ranges of cells placed back-to-back in the centre of the building.

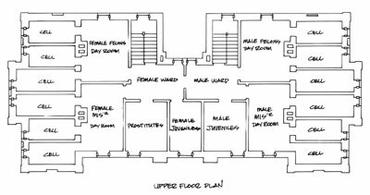

Designed for short-term incarceration (inmates were being held for trial or had been sentenced to terms of less than two years), these new jails often utilized more complicated internal plans than those employed in institutions designed for long-term incarceration. Institutions constructed to serve municipalities during the first half of the 19th century had been criticised as schools of criminality. Since inmates were housed together with limited supervision and nothing to do, experienced, hardened criminals took on leadership roles, passing the time by training younger inmates in the ways of crime. The new jails, by contrast, separated inmates by gender, age and level of criminality. The plan of the Ontario County jail at Whitby, built in 1852-53, illustrates the solution used by the architects, the Toronto firm of Cumberland and Storm. Levels, doors, corridors, and individual cellular confinement separated males from females, adults from youths, prostitutes from other inmates, and minor offenders from felons.

Federal and Provincial Jurisdiction

Under the British North America Act (1867), corrections became mainly a federal responsibility. Thereafter, sentences of two years or longer were served at institutions funded by the central government, while provincial prisons housed inmates sentenced to shorter penal terms. A facility expansion was required to accommodate the legislation. Several provinces erected new prisons. Ontario, for example, erected a new institution at Toronto in 1870-72 (Kivas Tully, architect) to replace Kingston Penitentiary, which became federal property. Between 1872 and 1878, the central government also began to open new institutions for long-term incarceration. These were located at Saint-Vincent-de-Paul, Québec (1873), Stoney Mountain, Manitoba (1877), New Westminster, British Columbia (1878), and Dorchester, New Brunswick (1880). Whether sponsored by the federal or provincial governments, these new institutions also used an Auburn-style layout modelled on the Kingston Penitentiary.

Work programs assumed a greater role in prison reform as the benefits of silent self-examination came to be challenged. The smaller institutions usually provided less sophisticated types of labour, though the Toronto institution originally included a railway car assembly plant that proved a financial failure. Using untrained inmates tended to be inefficient; the industries rarely yielded significant profits to the institution and many of the undertakings were short-lived. All prison-based industries faced opposition from manufacturers and labour groups, who felt that the use of cheap prison labour interfered with the open market. In 1886, the Dominion Government ended prison industries, a move that crippled efforts to train inmates for employment after release. Thereafter, labour programs in both federal and provincial institutions were largely limited to work such as cooking, farm operations and building maintenance and repair. These jobs supported the prison's operation and offered minimal vocational training. The vicious form of discipline advocated at Auburn was gradually moderated in its severity. Outside the federal system discipline was rarely as strict as it was at Kingston and the regimen of silence, the rule in the federal system until 1932, was rarely implemented.

Departures from the Auburn Layout

Some departures from the Auburn prison layout came in the early 20th century, when a few municipal and provincial governments sought alternative architectural approaches to correctional design. When the city of Montréal decided to replace its vastly outdated 1820s prison, a decidedly modern, technologically sophisticated complex was constructed in suburban Bordeaux (1908-13, designed by Jean-Omer MARCHAND and R. A. Brassard). This consisted of a central 12-sided domed hub from which sprang six cellblock wings that featured large outside cells ranged along the exterior walls. Whereas most earlier short-term institutions had offered very elementary work programs on the argument that only long-term prisons could actually affect work habits and offer satisfactory job training, the Bordeaux jail included state-of-the-art workshops. These were symbolically placed at the heart of the prison, in front of the cellblock and on either side of the administration building. The whole complex was placed within a five-sided compound surrounded by a double wall.

Ontario's Guelph Reformatory (1909-10, designed by John LYLE) was planned to cater to the needs of young offenders, those under the age of 30 who, correctional authorities believed, were most susceptible to reformation. It adopted a different, but equally innovative, design approach. Staff and inmate facilities were concentrated in a front-facing administration block that was linked by a long corridor to inmate accommodation wings. The resulting complex was in the shape of an "E."

Individual cellular confinement and dormitory living were both available at the Guelph Reformatory as were inmate kitchens and dining halls. Within the institution's 830-acre site, professionally designed spaces were set aside for a remarkable range of vocational programs, including a complete agricultural operation, shops for construction, metal, wood and enamel work, a fish farm, a quarry, construction, and the manufacture of shoes and cloth. The complex, which was serviced by its own railroad with access to (and a station on) the CPR mainline, also included a chapel, bathhouse, recreation hall and school. In a decided departure from earlier designs, the complex was not walled.

The provincial institutions at Guelph and Bordeaux were departures from the Auburn system in both program and design. The federal Department of Justice, on the other hand, only introduced new design approaches in the 1930s when planning its first medium-security prisons for young offenders at Collins Bay, Ontario, and Saint-Vincent-de-Paul, Québec (the latter was never built). Like the Guelph Reformatory, these institutions aimed to separate inmates under 30 who were not defined as incorrigible from the vast majority of prisoners who were repeat offenders. Both employed the "telephone pole" layout — a fronting administration building linked by a long corridor behind it to wings of specialized inmate and staff facilities. Inmates were housed in a mix of standard Auburn "inside" cells, unconnected with the cellblock's exterior walls, and outside cells with barred windows. Unlike Guelph, Collins Bay placed the institution's main buildings within impregnable, enclosing walls.

Canadian Prisons Need a New Model

In spite of these attempts to introduce change, the Auburn model persisted in the planning of both federal and provincial prisons. A notable example of the stranglehold it exerted on prison design was the federal government's Prison for Women at Kingston, where the architectural staff of the Department of Justice produced plans for a T-shaped structure very similar in layout to men's prisons of the 1870s. Extraordinary levels of security, including formidably thick outside walls, inside cells and heavy division walls were provided to hold a small group of inmates whose criminal records, a 1936 royal commission on the correctional system suggested, did not require such a rigid approach.

Two world wars, the Depression and Reconstruction delayed long-overdue design reforms between 1914 and 1960. With few exceptions, governments at all levels simply continued to utilise outdated facilities, often built to accommodate long-discredited correctional philosophies. The 1960s, however, initiated a wholesale reform of Canada's penal system. In 1960 a federal government departmental committee chaired by Allen J. MacLeod issued a path-breaking report on correctional planning to transform the federal system. In 1977, a parliamentary committee chaired by Mark MacGuigan updated and expanded the MacLeod report. Influenced by international trends represented by organizations such as the United Nations and informed by academic disciplines such as psychology, sociology, and criminology, the department proposed phasing out virtually all its existing prisons, buildings of the Kingston type that dated to the pre-1914 period. These would be replaced by new institutions embodying contemporary correctional thinking. The former Auburn-inspired model would yield to a multiple-model system with a broad range of institutional alternatives, including reformatories, halfway houses, juvenile detention centres and isolated work camps.

What characterizes contemporary correctional complexes is the variety of designs — each one tailored to program requirements. Security levels vary and are often achieved electronically. There has been a move to reduce the size of institutions from their former 500 to 1500 inmates down to approximately 200. Inmate living arrangements more closely resemble those outside the prison. Prisons often include up-to-date educational and vocational training facilities and allow for pre-release programs in socialization.

A shift to an emphasis on socialization (preparation of the inmate for a safe return to the community) is delivered through the concept of unit management, in which staff of various types are assigned to a group of inmates in an attempt to work cooperatively towards reformation and reintegration into society. The replacement of the linear cellblock layout by clusters of inmate living units (bedrooms around a common room) is an attempt to respond to this new emphasis in correctional philosophy.

The cluster approach has been applied to the design of new women's centres intended to replace the 1934 Prison for Women in Kingston, which shut its doors in 2000. Individual living units arranged like cottages in a village attempt to replicate non-institutional life. According to this model, the prison is a miniature community where inmates and staff live and work together in quasi-family situations. Placed in the midst of small cities, these institutions are designed to be integral parts of the surrounding neighbourhood and substitute electronic surveillance for the traditional reliance on staff supervision and walls. One of the five women's centres functions as an Aboriginal healing lodge, its design informed by First Nations philosophies.

Special Handling Units (SHU), designed to accommodate Canada's most dangerous inmates on a short-term basis, are at the other end of the security scale. After experiments in the late 1970s at Millhaven (Ontario) and Laval (Québec), the federal government erected purpose-built institutions at Laval and at Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, both opened in the mid-1980s. These low-population, high-security units require, for reasons of protection, a minimum of direct contact between staff and inmates and are highly dependent on surveillance by technology. As of 2013, there was one SHU (located in Sainte-Anne-des-Plaines, Québec) in Canada, along with various other maximum-security and multi-level institutions.

Correctional Service Canada and Aboriginal Peoples

No Aboriginal records refer to the concept of long-term incarceration as a form of punishment in Indigenous communities. Those who deliberately departed from tribal norms or traditions faced sanctions such as temporary or permanent banishment or death. Today, Correctional Service Canada accommodates the needs of Indigenous communities through a range of centres including institutions, Aboriginal healing lodges, community residential facilities, and parole offices. These comprise the full spectrum of correctional facilities in Canada.

The Future of Prisons

Implementing the MacLeod report led to a remake of the federal correctional system: the eight institutions of 1958, six of which predated the First World War, increased to 56 by 1978.

Since 1960, most provincial and municipal prisons and jails, the majority of them predating the First World War, have been replaced by new institutions. As with their federal counterparts, Auburn-styled rows of inside cells were abandoned for less institutional living quarters. These changes in philosophy can be seen when comparing Toronto's municipal correctional facility of 1977 to that of William Thomas's 1864 Don Jail to its west. The two buildings reflect the views of their respective eras on prison design as serving to rehabilitate or punish.

The prison population in Canada has in fact dramatically risen over the past 40 years, from 90 per 100,000 in 1972 to 142 per 100,000 in 2012, largely the result of mandatory sentencing for gun and drug crimes. This has inevitably led to overcrowding in Canadian prisons and the need to build new ones. The new generation of prisons, like the Edmonton Remand Center (opened in 2013), are technologically advanced. Electronic and building technologies (video and audio surveillance, automated entry systems and tempered steel and other high-strength materials) provide the security once guaranteed by walls and high staffing ratios.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom