In the 1950s, Saskatchewan was home to some of the most important psychedelic research in the world. Saskatchewan-based psychiatrist Humphry Osmond coined the word psychedelic in 1957. In the mental health field, therapies based on guided LSD and mescaline trips offered an alternative to long-stay care in asylums. They gave clinicians a deeper understanding of psychotic disorders and an effective tool for mental health and addictions research. Treating patients with a single dose of psychedelic was seen as an attractive, cost-effective approach. It fit with the goals of a new, publicly funded health-care system aimed at restoring health and autonomy to patients who had long been confined to asylums.

Click here for definitions of key terms used in this article.

Background: Discovery of LSD

In 1938, chemist Albert Hofmann first made d-lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) in a lab in Basel, Switzerland. It remained untouched until 16 April 1943. That day, as Hofmann synthesized the drug, he got some on his fingertips. It was absorbed through his skin, and he took the first recorded LSD trip. Three days later, he tried it again and rode his bicycle home while experiencing the “dream like” and “intoxicating” effects of LSD that changed his sense of perception.

The hallucinogenic properties of LSD quickly attracted attention from researchers. Between 1950 and 1961, medical journals published over 1,000 scientific articles on LSD. They included studies ranging from animal experiments to clinical uses with humans.

Psychiatric Drugs in the 1950s

The 1950s brought major changes to Western psychiatry, namely the widespread introduction of psychopharmaceuticals. Anti-depressant, anti-psychotic and anti-anxiety medications poured onto the market during this decade. They made it possible to imagine new ways of managing illness. There was great optimism that psychopharmaceuticals would transform mental health care.

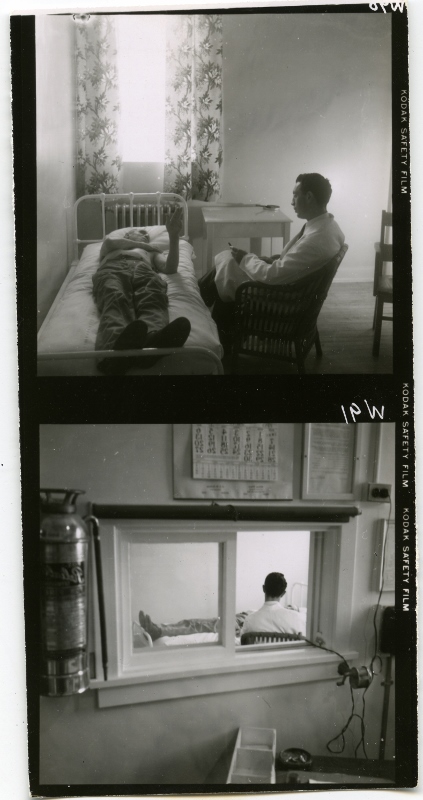

This tidal wave of interest around psychoactive substances included LSD. However, LSD offered a very different approach to healing. Rather than a lifetime of pill-popping solutions, the psychedelic approach favoured a single-dose method. The idea was that the subject would gain insight and perhaps acceptance of their behaviour during their experience. In other words, it was an intensive psychotherapy session that some people believed was the equivalent of 10 years of therapy.

Saskatchewan’s Research Program

In 1944, Saskatchewan residents elected the first socialist government in North America. The new premier, Tommy Douglas, had promised to dramatically reform the health-care system. Over the next 17 years, he would build the framework for a national program of medicare. As he began those reforms, Douglas recognized the need to invest in medical research alongside public policy changes. He recruited researchers from far beyond Saskatchewan to create a culture of experimentation in the province.

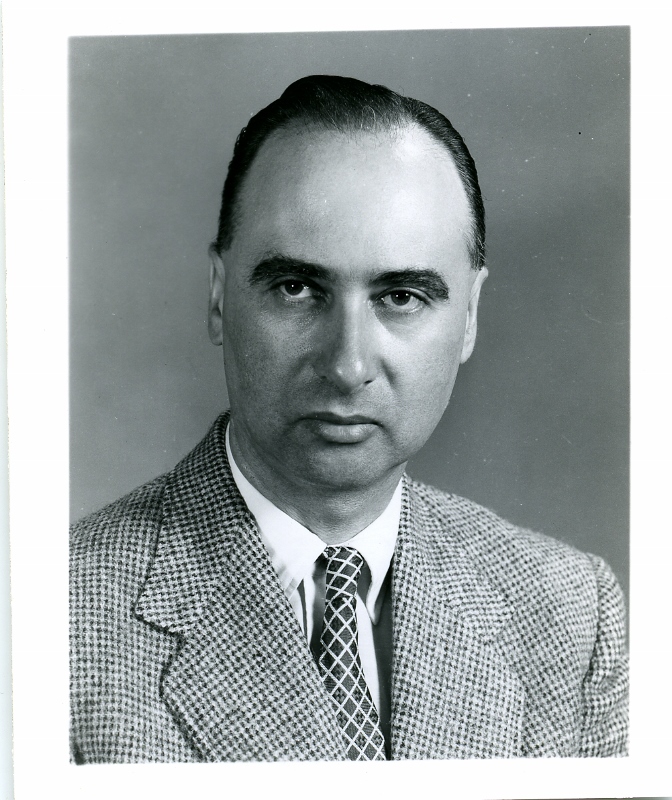

Humphry Osmond and Abram Hoffer

British psychiatrist Humphry Osmond arrived in Saskatchewan in 1951. He had developed an interest in hallucinations and psychotic disorders during his practice in London. Osmond became clinical director, and later superintendent, of the Saskatchewan Mental Hospital in Weyburn.

One of the largest asylums in North America, the Weyburn Mental Hospital was grossly overcrowded. For most patients, admission was a life sentence. On the outside, the hospital and its gardens were impressive and well kept. Inside, though, patients suffered. Directors had created scandals by hiring staff based on political connections rather than experience or skill. Osmond was determined to transform mental health care at Weyburn and beyond. He would begin with a serious study of hallucinations and psychosis.

Soon after arriving in Saskatchewan, Osmond met fellow psychiatrist and biochemist Abram Hoffer. The Saskatchewan native had recently finished medical school in Toronto and become a researcher with the Psychiatric Services Branch of the provincial public health department in Regina. Osmond and Hoffer became significant collaborators, despite the distance that separated them. They were connected by a desire to improve mental health care and support the provincial health-care reforms.

Research Objectives

Humphry Osmond and Abram Hoffer’s research program quickly developed two significant objectives. First, using LSD and mescaline (from the peyote cactus), Osmond continued his earlier work on model psychoses. He proposed that LSD mimicked the psychotic effects of schizophrenia. By producing such a model of a disease, he thought that one could better understand patients and share their feelings. To that end, health-care staff could gain valuable insight into their patients by temporarily experiencing mental illness through a guided LSD trip. Osmond and Hoffer also thought that if they could create a state of psychosis by giving someone a mix of chemicals, a true psychosis might be the result of a chemical imbalance. This hypothesis encouraged researchers to look carefully at brain chemistry when studying disorders like schizophrenia.

The second research objective concerned alcoholism. Osmond and Hoffer suggested that an LSD trip also mirrored alcoholic patients’ terrifying accounts of “hitting rock bottom.” Patients with alcoholism often refused help until reaching that stage. Osmond and Hoffer reasoned that they could hijack the natural course of the disease by giving alcoholics LSD before they reached rock bottom. By intervening earlier, they hoped to avoid some of the damage to the body from liver disease. They also hoped to avoid the criminal and aggressive behaviour that often came with alcoholism. They began publishing their results in medical journals and their research quickly drew attention.

Coining the Word Psychedelic

In March 1953, Humphry Osmond received a letter from well-known British author Aldous Huxley, who had learned of his research program. The two corresponded, and Huxley asked whether he could have a guided trip. Osmond flew to Los Angeles to meet Aldous and Maria Huxley and to bring them mescaline. Their meeting quickly forged a friendship that lasted until Huxley’s death in 1963. Their friendship also produced the word psychedelic. “To fathom Hell or go angelic / Just take a pinch of PSYCHEDELIC,” Osmond wrote to Huxley. This was in response to Huxley’s rhyme proposing a similar term of Greek origin: “To make this trivial world sublime, / Take half a gramme of phanerothyme.” In 1957, Osmond presented the term psychedelic in a medical paper, and it entered the English language.

Saskatchewan Leads Health Reforms

Huxley was not the only person outside Saskatchewan and the psychiatric community who recognized the potential in psychedelics. Journalists, architects, nurses, hospital directors, artists, engineers, musicians, theologians and Indigenous healers (see Shaman) began seeking advice from the Saskatchewan researchers. Charismatic colleagues joined Humphry and Osmond’s project. These included psychologist Duncan Blewett (who started the first psychology program at the University of Saskatchewan’s Regina campus), Sven Jensen in Swift Current (who elevated the role of spirituality in addictions therapy), and Colin Smith, who worked first at Weyburn and then in Regina (and helped steer health policy decisions in psychiatry).

During the 1950s, Saskatchewan became an important destination for health-care reforms and psychedelic research. Curious thinkers and reformers worked together on a diverse and far-reaching set of studies, with promising results. The alcoholism studies, which followed patients for up to two years, showed 50–90 per cent recovery rates. Hospital reforms included changing the designs of hospitals and training psychiatric nurses to help patients avoid frightening hallucinations. Staff were also trained to provide comfort and empathetic care.

Decline of Psychedelic Research

In the early 1960s, the heyday of psychedelic research began to fade. This was partly due to the slowing momentum behind Tommy Douglas’s political experiment. Saskatchewan struggled to put the last pieces of medicare in place after the divisive provincial election of 1960. The next year, Douglas resigned as premier to lead the federal New Democratic Party. Then came the Saskatchewan doctors’ strike over medicare in July 1962. By the end of that year, Canadians learned about the birth defects associated with the drug thalidomide ( see Frances Oldham Kelsey). This sparked Parliamentary debates on the classification and prohibition of drugs and placed LSD under political scrutiny.

Osmond left the province in 1961 for a job at Princeton University. He later settled in Alabama, where he worked to reform another major mental hospital.

The Canadian government ultimately allowed research with LSD to continue. However, it changed the regulations, making researchers apply directly to the federal minister of health for permission to do these studies. This practice continued for several years. By the end of the decade, however, there was widespread concern about recreational use and abuse of psychedelics (see Nonmedical Drug Use).

Change in Cultural Attitudes

In the early 1960s, reports of a black market in acid spilled into mainstream news. These reports raised alarms about a drug that caused hallucinations, “madness” and violence. Psychedelic researchers quickly recognized the emergence of such a market despite their efforts to prevent it. With these negative associations, cultural attitudes toward psychedelics changed. Research units came under pressure to halt their research programs.

Humphry Osmond and Abram Hoffer recognized that the association between psychedelics and violence threatened medical research. So did acid’s reputation as a drug that caused people to reject authority. Osmond wrote to American officials, pleading with them to help protect medical research. He visited known black-market suppliers and asked them to deal cautiously. He even scolded Timothy Leary, a former Harvard psychology professor turned self-appointed acid guru. Leary suggested that everyone should use psychedelics to “tune in, turn on, and drop out.” He and others had helped make a strong popular association between psychedelics and counterculture. In the minds of many, psychedelics became linked with pleasure-seeking or even dangerous behaviour. (See also Hippies.)

Researchers tried to keep exploring therapeutic uses of psychedelics in medicine. However, drug regulators throughout the Western world clamped down. They increased red tape, making psychedelic research next to impossible. Psychedelic researchers also claimed that they could not compete with a growing lobby of drug companies that promoted daily use of a product over a single-dose therapy.

For the next 50 years, psychedelic research remained relatively quiet. Anti-drug campaigns further cemented an image of LSD as dangerous, with the idea that it permanently changed brain chemistry or triggered psychosis.

Importance

The 21st century has seen a renewed interest in psychedelics. There is growing support for bringing back psychedelic science. In many ways, that work is picking up where the 1960s research trailed off. Research on addictions, post-traumatic stress disorder, models of madness, and end-of-life care is gaining momentum. Some observers are describing it as a psychedelic renaissance.

Humphry Osmond’s ideas for reform have had a lasting influence. Researchers are again crossing geo-political and professional boundaries to explore the role of psychedelics in transforming ideas about health and wellness. In the 21st century, the context is somewhat different. We no longer treat mental illness with lifelong confinement in psychiatric hospitals. But critics say that the widespread use of daily drug treatments for mental conditions also has negative side effects. Evidence-based medicine and current approaches to policy are questioning whether profit-making has overly informed the regulations that support the sale of these drugs (see also Pharmaceutical Industry). Researchers are also seeking new ways to treat alcohol and tobacco addictions. These substances cause serious harm to health and significant cost to health-care systems. But because they are large sources of tax income, governments are unwilling to ban their use.

A new generation of researchers is beginning to tackle the relationship between drug regulation and the health-care economy. They are creating space for psychedelic research and asking why a cheaper therapy has not been carefully considered. These ideas are not new, however. Concerns for cost were part of what guided research in 1950s Saskatchewan, alongside a desire to better understand how patients with psychosis understood themselves.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom