Racial segregation is the enforced separation of different racial groups in a country, community or establishment. Historically, the racial segregation of Indigenous peoples in Canada has been enforced by the Indian Act, reserve system, residential schools, and Indian hospitals, among other programs. These policies interfered with the social, economic, cultural and political systems of Indigenous peoples, while also paving the way for European settlement across the country. The segregation of Indigenous peoples in Canada must be understood within the history of contact, doctrines of discovery and conquest, and ongoing settler colonization.

European Settlement and the “Indian Problem”

Historically, Indigenous peoples were considered a threat to European settlement and expansion. During the creation of the Numbered Treaties (1871–1921), for example, the federal government made agreements with various First Nations as a means of developing their territories for industrial development and White settlement. While many Indigenous signatories were reluctant to sign the treaties, they eventually did so because of a lack of food (due to the declining bison on the plains) and the vast spread of infectious diseases, among other reasons.

With settler colonization came the framing of the “Indian Problem” — the prevailing belief that Indigenous peoples needed to be assimilated into Euro-Canadian culture because their traditional ways were considered “uncivilized” and “immoral.” The term “Indian Problem” is attributed to Duncan Campbell Scott of Indian Affairs. In 1918 he said,

I want to get rid of the Indian problem. I do not think as a matter of fact, that the country ought to continuously protect a class of people who are able to stand alone… Our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic and there is no Indian question, and no Indian Department...

As part of a nationwide response to solve the “Indian Problem,” the government and missionaries used systems of assimilation, such as residential schools and the Indian Act, with widespread public support.

The Indian Act

The Indian Act of 1876 was designed to control and assimilate First Nations peoples; it does not deal with the Inuit or Métis. The Indian Act disrupted Indigenous systems of governance, restricted access to legal support, and banned the formation of political organizations and cultural practices like potlatches and the Sun Dance. The Act also legally deemed First Nations peoples with Indian Status as wards of the state. Until 1951, Status Indians were not considered citizens and, until 1960, did not have the right to vote in federal elections. (See also Indigenous Suffrage in Canada and Indigenous Women and the Franchise.)

Status Indians could become enfranchised — meaning they legally lost Status rights and could then vote in elections, for example — if they willingly chose to or they joined the Armed Forces. Many Indigenous women lost their Status, not by choice, but because the Indian Act took away those rights if they married a person without Status.

Enfranchisement did not always guarantee equality for Indigenous peoples. For example, Tommy Prince, war hero and one of Canada’s most decorated soldiers, returned home from the front lines and faced systemic racism. Despite his service to Canada, he was not able to vote and was not treated the same as other veterans. (See also Indigenous Peoples and the World Wars.)

Important reforms were made to the Indian Act in 1951. Indigenous peoples were now viewed as citizens. Among other changes, the potlatch ceremony ban was lifted, and Indigenous peoples could enter and be served (with the exception of alcohol) at establishments and pool halls. The Act was significantly amended again in 1985. Arguably one of the most important changes in 1985 was that many women who had lost their Status rights as the result of a marriage regained those rights.

While the Indian Act has been amended over the years, it is still seen as problematic. People with Indian Status are still governed by a different set of regulations than other individuals in Canada. In this way, the Indian Act can be understood as an official policy of racial segregation.

Reserves and the Pass System

The reserve system is governed by the Indian Act and relates to First Nations. Inuit and Métis normally do not live on reserves, though many live in communities that are governed by land claims or self-government agreements.

After the signing of the Numbered Treaties from 1871 to 1921, Indigenous peoples were pushed onto small tracts of land that were “reserved” for them. In many cases, these lands have been described as less desirable and posed significant challenges for agriculture and traditional sustainability such as hunting, trapping and fishing.

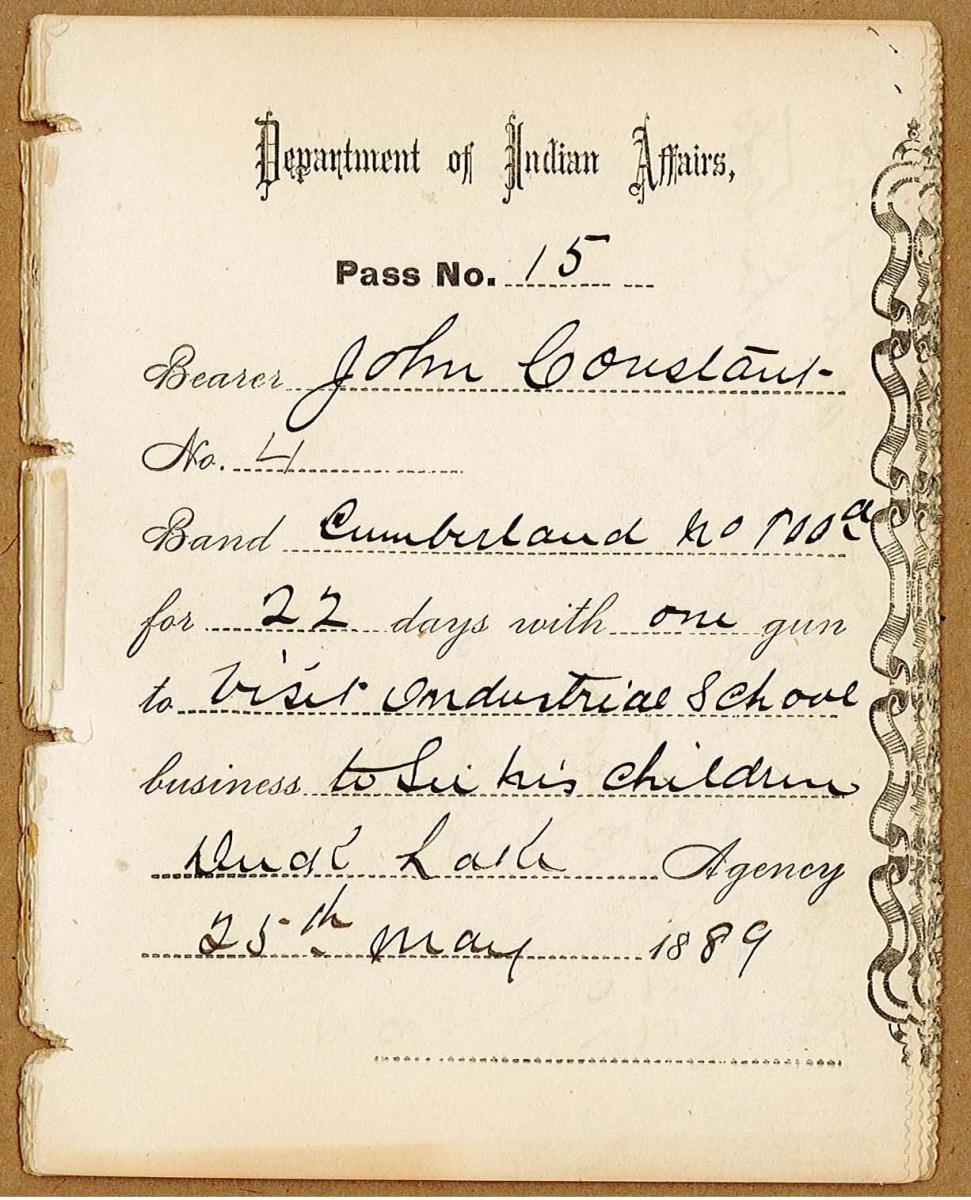

Another challenge on reserves was the pass system. From 1885 to about the early 1900s, the federal government developed a process by which Indigenous people had to present a travel document authorized by an Indian agent in order to leave and return to their reserves. The pass system was created to control and restrict the movement of Indigenous peoples off reserves. Used in conjunction with policies like the Indian Act, the pass system was part of an overall policy of assimilation that has had lasting impacts on generations of Indigenous people.

Today, reserves are still governed by the Indian Act. The federal government administers funding for on-reserve education, social and health services. For most other Canadians, including the Métis, these services are funded through provincial and territorial governments. (The federal government administers Inuit health programs.) In some cases, First Nations who have achieved self-government manage much of their own affairs.

Though never placed on reserves, the Inuit and Métis have suffered from land dispossession. The introduction of missionaries and European ways of life in the North resulted in the loss of Inuit land, economy and culture. Many Inuit were particularly affected by the High Arctic relocations in 1953 and 1955, when they were forced off their homelands to inhabit a different part of the Arctic. The Inuit were assured plentiful wildlife, but soon discovered that they had been misled, and endured hardships. The effects have lingered for generations.

For the Métis, colonial dispossession created various fringe communities in British Columbia and the Prairies, such as Rooster Town. As urbanization increased, Métis people were forced to relocate. These moves disrupted social support networks of neighbours and kin, and reduced Métis independence. (See also Métis Settlements.)

Residential Schools

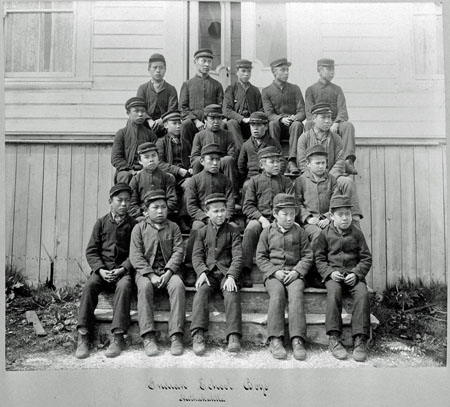

Various Canadian churches initially designed schools to assimilate Indigenous children. These schools date back to the 1600s. A system was formally administered by the federal government in 1883. Children in these schools were forcibly removed from their families and communities and segregated by gender. Students were subjected to multiple forms of abuse, malnourished, and made vulnerable to diseases as a result of poor nutrition and overcrowding. The last federally funded residential school, the Gordon Residential School in Saskatchewan, closed in 1996.

Today, education for First Nations communities is federally administered, in comparison to provincially-funded schools for other children. Reserve schools are chronically underfunded. Youth from northern communities also have the difficult decision of either leaving home to go to schools in far away cities or quitting school early. (See also Education of Indigenous Peoples in Canada.)

Segregation in Health Care

With colonization came the suppression of Indigenous systems of healing. Amendments to the Indian Act in the late 19th and early 20th centuries criminalized and prohibited Indigenous healing practices. These laws, combined with poor living conditions, poverty, loss of land and declining access to food resources, had devastating and ongoing consequences on the health of Indigenous peoples.

During the 20th century, the government created Indian hospitals to care for First Nations peoples and Inuit. There was widespread fear that Indigenous peoples would spread sickness, namely tuberculosis, to white settlers. Indian hospitals did not provide Indigenous medicines or holistic notions of illness. Instead, they were intended to further assimilate First Nations peoples and Inuit. The history of Indian hospitals was one of a deeply entrenched system of racially segregated care.

Today, care for on-reserve First Nations (and Inuit) is still administered federally, and provincially for others. Indigenous peoples do not receive the same quality of care as other people in Canada. One striking example of this is the story of Jordan River Anderson, a young boy from Norway House Cree Nation in Manitoba. He died at the age of five after waiting for home-based care that was approved when he was two years old but never arrived because of a financial dispute between the federal and provincial governments. Jordan’s Principle, a child-first principle, was put in place to ensure a tragedy like this never happens again.

Significance

The segregation of Indigenous peoples is deeply embedded in the development of Canada. As a result, Indigenous peoples continue to face social injustices across the country. The final reports of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada and the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women speak to the history of segregation as well as to the ongoing work of reconciliation.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom

.jpg)