Robert Laidlaw MacMillan, cardiologist (born 23 May 1917 in Toronto, Ontario; died 5 September 2007 in Toronto, Ontario). Robert MacMillan was a cardiologist and professor of medicine at the University of Toronto and co-founder of the world’s first coronary care unit in 1962. He is the father of acclaimed historian and author Margaret MacMillan.

Early Life and Education

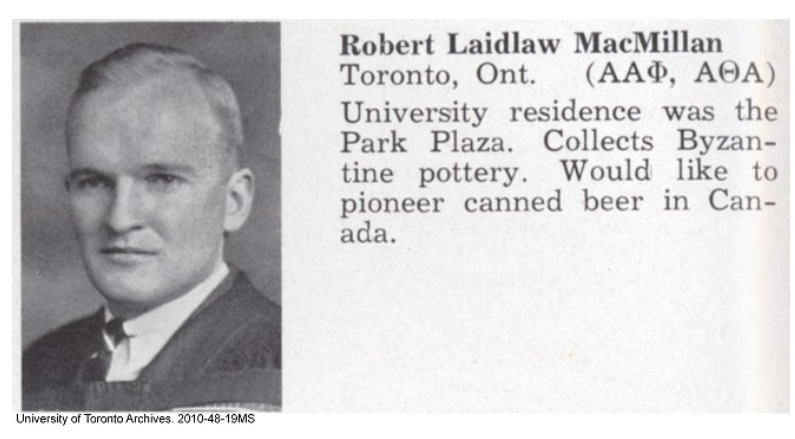

Robert MacMillan was born into a family of medical practitioners. His father, Robert Johnson MacMillan, graduated from medical school at the University of Toronto in 1906, served in France with the Royal Army Medical Corps during the First World War and became a specialist in anesthesia at Wellesley Hospital. His mother, Elizabeth Merle Laidlaw, was a nurse who graduated from the Toronto General Hospital Training School for Nurses in 1905. When MacMillan was around 13, his family spent a year in Switzerland, where he learned French. After the family returned to Toronto, MacMillan and his brother Hugh completed their secondary education at the University of Toronto Schools. In 1938, MacMillan graduated from Trinity College at the University of Toronto with an honours degree in biological and medical sciences; he earned his medical degree from the University of Toronto in 1941.

Marriage and Children

Robert MacMillan met Eluned “Lyn” Carey Evans, a granddaughter of former British prime minister David Lloyd George, in 1939. At the time, Carey Evans was living at St. Hilda’s College, the women’s residence at Trinity College, taking medical courses at the University of Toronto after the outbreak of the Second World War made it impossible for her to return home to the United Kingdom. They were married in the Trinity College Chapel in 1942 and had five children: historian and author Margaret Olwen (born in 1943), CBC journalist Ann Elizabeth (born in 1946), financier Thomas Carey (born in 1948), urologist Robert David Hugh (born in 1951) and energy consultant David John (born in 1953).

Their marriage was a happy one. In her 2020 essay “My Mother’s House,” Margaret MacMillan described her parents and her childhood home, writing “[My mother] could have married (and perhaps nearly did) a rich, stuffy Toronto young man, but by luck and because she was an acute judge of people, she married my father, who for the next half-century thought almost everything she did was perfect and admirable.” In a 2021 H-Diplo essay, “On Becoming an Historian,” MacMillan once again paid tribute to her parents, writing, “I was lucky, too, in my parents, who believed strongly in education and, as important, in allowing their children to follow their own interests. Our house was full of books, and we were encouraged to read whatever we wanted. And our parents told us stories…My father’s were about a much smaller and different Toronto or being a doctor in the Canadian navy during the war.”

The Second World War

After graduating from medical school in 1941, Robert MacMillan interned at Toronto General Hospital and then enrolled in the Royal Canadian Navy, becoming a surgeon lieutenant commander on HMCS Prince Robert. The ship was one of several liners that were converted for naval use during the war. The Prince Robert was constructed in 1930 for Canadian National and had transported King George VI and Queen Elizabeth (later the Queen Mother) from Vancouver to Victoria during the 1939 Royal Tour. It was purchased at the beginning of the Second World War by the Royal Canadian Navy and converted to an armed merchant cruiser in 1940 and an anti-aircraft cruiser in 1943. MacMillan served in the United Kingdom via the Panama Canal on HMCS Prince Robert, which became the Royal Canadian Navy’s largest and most heavily armed ship, sailing more operational miles than any other Canadian naval vessel. MacMillan was demobilized and returned to civilian medicine in 1946. (Likewise, HMCS Prince Robert returned to civilian life, serving as a passenger ship until 1962.)

Cardiology

In 1947, Robert MacMillan completed postgraduate studies in London and Oxford and became a member of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. He then returned to Canada in 1948 to begin a decades-long career as a cardiologist at Toronto General Hospital. MacMillan and his colleague Kenneth Brown researched how to reduce the high mortality rates among patients recovering from acute heart attacks, which was 40 per cent in the early 1960s.

In 1962, Brown and MacMillan established a groundbreaking coronary care unit at Toronto General Hospital, funded by federal and provincial grants, as well as a substantial private donation from Toronto brass manufacturer and philanthropist Percy Gardiner. Patients were connected to newly developed electrocardiogram machines and monitored 24 hours a day. Nurses were trained to recognize complications and begin life-saving procedures to adjust or restart heartbeat rhythms while awaiting the arrival of doctors. The approaches adopted in the new coronary care unit reduced mortality rates by 10 per cent.

Brown and MacMillan presented their results in a 1963 article in the medical journal The Lancet and were acclaimed for founding the world’s first coronary intensive care unit. That same year, MacMillan, Brown, Hugh Smythe and William T. Mustard established the Blood and Vascular Disease Research Unit at 86 Queen’s Park in Toronto, later the site of the McLaughlin Planetarium from 1968 to 1995.

In 1965, MacMillan became the first John Oille Scholar at the University of Toronto for teaching, research and patient care in the fields of cardiology and cardiorespiratory diseases.

Brown wrote to cardiologist and author Harold N. Segall for the 1988 book Pioneers of Cardiology in Canada 1820–1970: The Genesis of Canadian Cardiology:

I think that the greatest thrill of my career has been my good fortune to be closely associated with Dr. R. L. MacMillan and the fact that, jointly, he and I set up the first coronary care unit anywhere in the world. When we opened up our coronary unit at the Toronto General Hospital and admitted the first patient on March 13, 1962, we did not know what to expect from this approach, but it appears now that this type of care has made some definite improvement in the mortality figures for this dread disease.

MacMillan maintained an extensive medical practice and had a long career as a professor of medicine at the University of Toronto. He became an assistant professor in 1965, an associate professor and a senior staff physician in 1968 and a professor of medicine and head of the division of general internal medicine at Toronto General Hospital in 1976.

Later Life

Robert MacMillan retired from teaching in 1982, at the age of 65, but maintained his medical practice for another decade. In retirement, he spent time at his farm in Vaughan, where he maintained an apiary. His hobbies included canoeing, scuba diving, hiking, camping, playing tennis and backcountry skiing. He survived a heart attack in 2001, reading his own cardiogram and diagnosing himself with a clot in his heart. He died of complications from heart disease in Toronto in 2007.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom