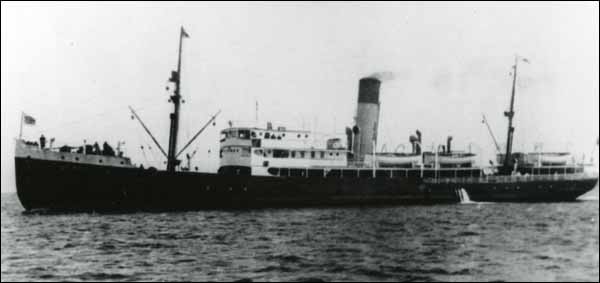

The SS Caribou was a passenger and train ferry that operated in the Cabot Strait between Port aux Basques, Newfoundland and North Sydney, Nova Scotia. On 14 October 1942, the German submarine U-69 sank the vessel, causing the worst loss of life in Canadian waters during the Second World War.

Construction and Service

Caribou was a steel 2,222-tonne steamship built in the Netherlands in 1925. It was purchased by the government of Newfoundland later that year. (Newfoundland joined Canada in 1949.) The 81-metre-long ferry travelled at a maximum speed of 15 knots. On arrival, Caribou’s hull was strengthened for the ice that would be encountered during winter crossings.

On the evening of 13 October 1942, Caribou departed North Sydney for the eight-hour, 178-kilometre crossing. It was accompanied by the Bangor-class minesweeper, HMCS Grandmère. Aboard were 237 people: 191 passengers (118 service personnel and 73 civilians) and 46 crew. Passengers included several mothers with children; many of the crew were related. Because German submarines had penetrated the Gulf of St. Lawrence and torpedoed merchant vessels and warships, Captain Benjamin Tavernor sailed with lights out and followed an indirect route in accordance with wartime regulations. (See Battle of the St. Lawrence and Battle of the Atlantic.)

U-69 was patrolling the area on the surface and by chance sighted the shadowy forms of two ships shortly before midnight. Its captain, Ulrich Gräf, remained on the surface and moved ahead of the two ships to take up a good position to launch his torpedoes. At the time, Grandmère was screening Caribou from astern, consistent with naval instructions.

Sinking of the SS Caribou

At 3:21 a.m. Atlantic Daylight Time (3:51 in Newfoundland), Gräf fired a torpedo at a range of 650 metres; it struck the ferry’s starboard side amidships 43 seconds later. The damage was instantaneous and catastrophic. The ferry’s boilers exploded and destroyed several lifeboats and rafts. Frantic family members tried to find each other in darkened cabins and corridors before they fought their way through rushing seawater to get onto the deck.

Survivors described the terror and “indescribable chaos” before the ferry went under four minutes later. Once in the water, people clung to any piece of floating debris they could find. A lucky few managed to scramble onto the remaining lifeboats and rafts, some of which were overturned. Even getting into a lifeboat did not guarantee survival. In their haste to get out of their cabins, many passengers were dressed only in their nightwear. Once launched, two lifeboats capsized due to overloading, tossing their chilled occupants into the ice-cold water.

Amid the panic, some individuals gave their lifebelts to others. Naval Nursing Sister Margaret Brooke was later made a Member of the Order of the British Empire for her ultimately futile efforts to save the life of her travelling companion, Nursing Sister Agnes Wilkie. Throughout the night, people recited the Lord’s Prayer and sang hymns.

Pursuit and Rescue

Grandmère’s captain, Lieutenant James Cuthbert, briefly saw U-69 on the surface after the torpedo struck home and turned to ram. U-69 immediately dived, so Cuthbert dropped a pattern of six depth charges over the spot, but without effect. Conditions were difficult, and Grandmère could not maintain constant contact with its rudimentary sonar. Whenever fleeting contact was established, the minesweeper fired additional depth charges. However, the submarine escaped.

At 5:20 Atlantic Daylight Time, Cuthbert gave up the hunt and returned to pick up survivors. He took 103 on board, two of whom later died. Grandmère then resumed its search for the submarine. At 8:20, five other warships and several Port aux Basques fishing vessels took over the search. Cuthbert took the survivors back to North Sydney. In total, 31 crew and 136 passengers, including women and children, were killed.

Fatalities included all but one of the children aboard, as well as several mothers. The lone child survivor, a 15-month-old baby, had been thrown overboard by his mother, who then jumped to her death. Among the crew, Captain Tavernor and his two sons, plus several sets of brothers were lost. This was a blow to small, close-knit Newfoundland communities. The sinking brought the war close to home and caused widespread outrage in Canada and Newfoundland. In February 1943, the destroyer HMS Fame sank U-69 east of Newfoundland, killing all 47 aboard.

Legacy

A 1929, two-cent Newfoundland stamp depicts Caribou and is inscribed “S.S. ‘CARIBOU’ 9 HOURS TO SYDNEY, N.S.”

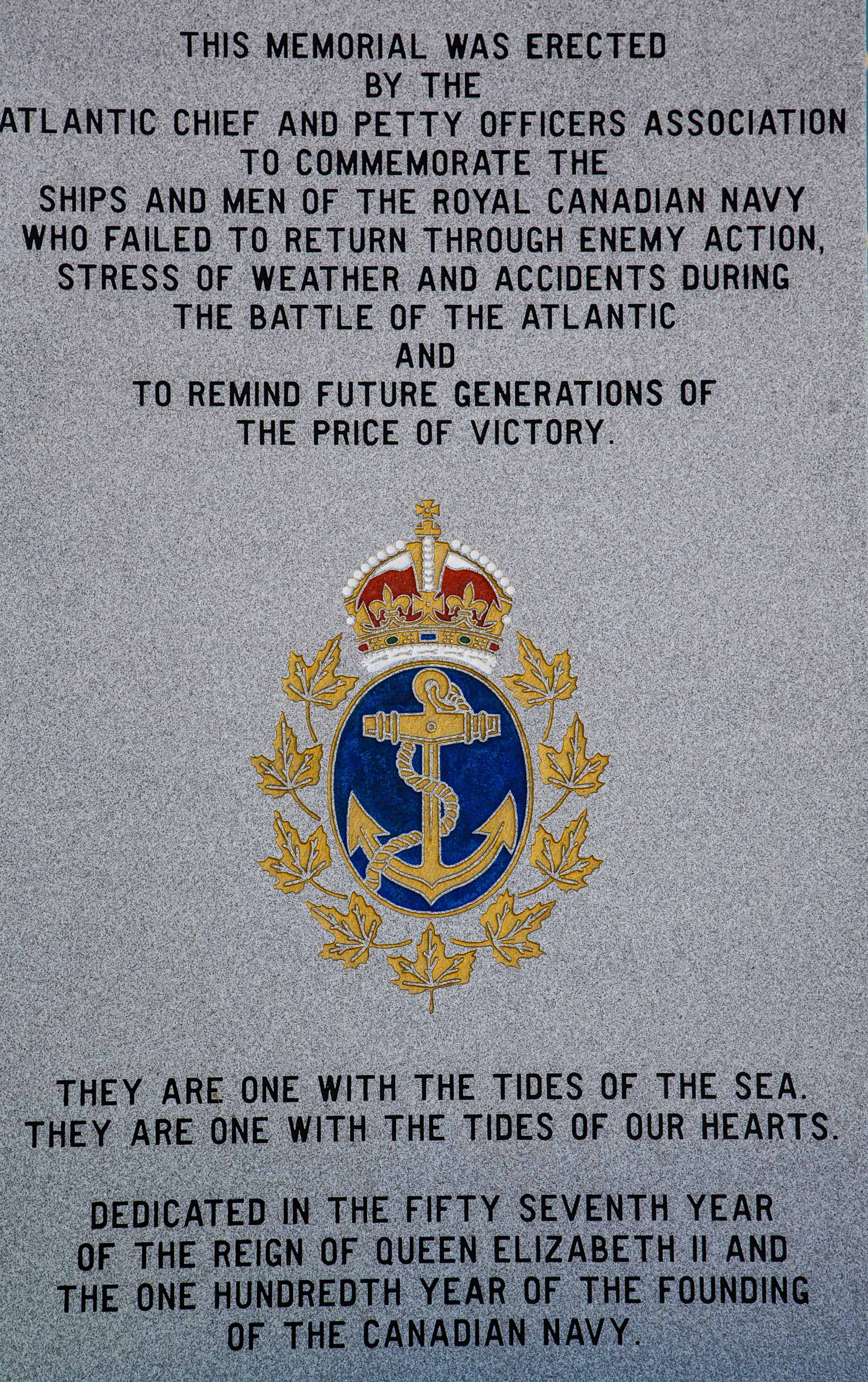

In Port aux Basques Memorial Park, a memorial to Caribou’s victims stands between two pillars, which list the community’s wartime casualties. The town’s annual Remembrance Day service includes a memorial for the Caribou.

The MV Caribou was a CN Marine ferry named in honour of the original Caribou. It serviced the North Sydney-Port aux Basques crossing between 1986 and 2010.

Did you know?

During the Second World War, Canada used daylight saving time all year round, as did the United States. Most countries used some sort of daylight saving time during the war. Great Britain, for example, put the clocks ahead one hour during the winter months and two hours during the summer. To make matters more confusing, Newfoundland, which was a separate dominion at the time, had (and has) its own unique time zone, UTC-3:30. This helps explain why authors provide different times for the sinking of the SS Caribou. Some, for example, state that the ferry was torpedoed at 2:21 a.m. Atlantic Standard Time, while others — including this article — state that it happened at 3:31 a.m. Atlantic Daylight Time (3:51 a.m. in Newfoundland).

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom