The sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus) has the largest brain in the animal kingdom. It is also the largest toothed whale species and has the widest global distribution of all marine mammal species. The name “sperm whale” comes from the substance spermaceti, which is found in the sperm whale’s head and is suspected to play a role in echolocation. These whales are specially adapted to hunt in the deep ocean, where there is no light.

Description

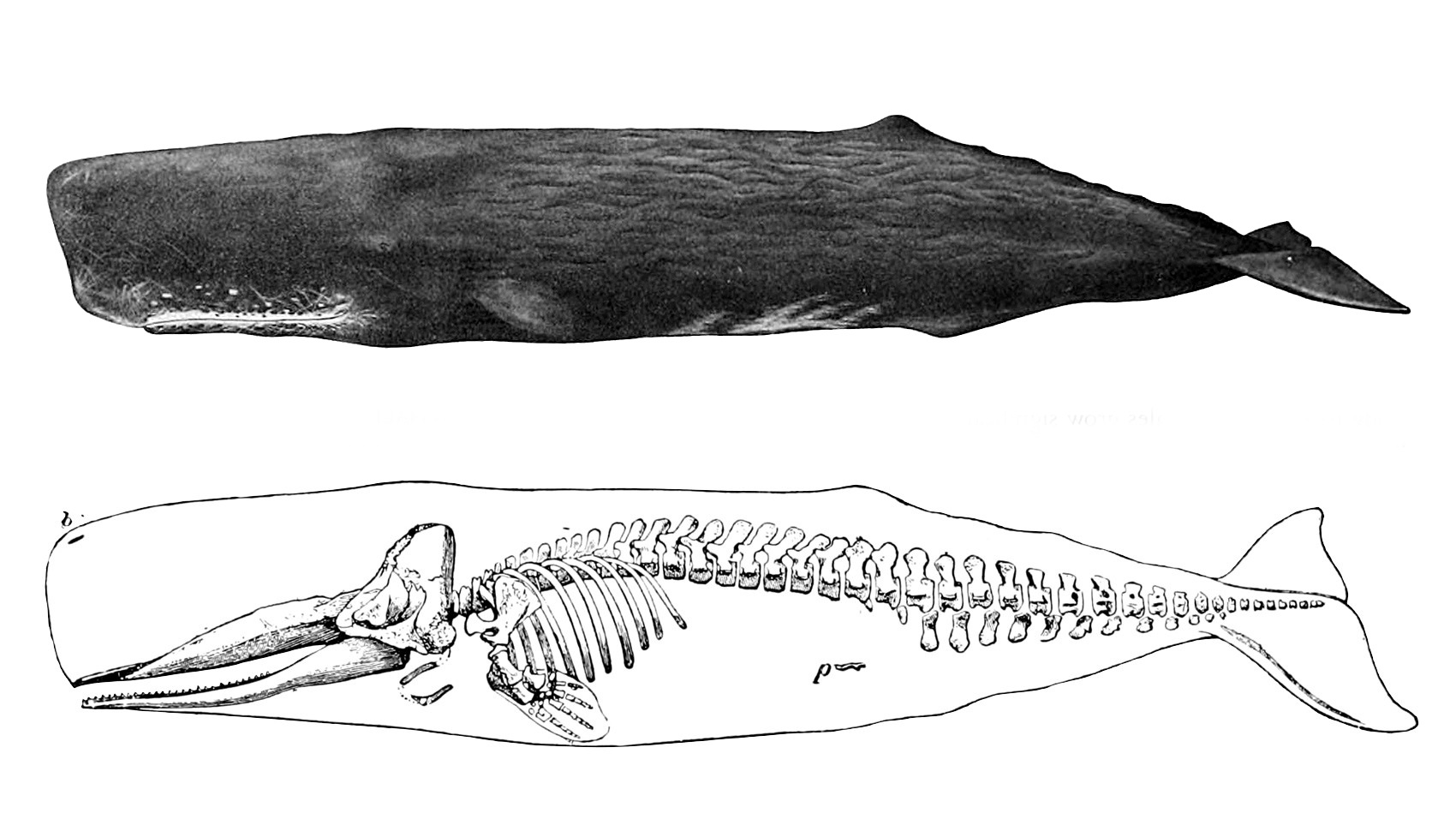

Sperm whales have a dark grey wrinkled body with a large square-shaped head that accounts for one-third of their body length. These giants weigh between 15 and 50 tonnes on average and measure 11–18 m, with males being larger than females. A unique trait of the sperm whale is its single blowhole pointing slightly to the left. The fins do not resemble those of other large whales; the pectoral fins are small and paddle-shaped, and the small, hump-like dorsal fin leads to visible bumps that follow the spine down to a triangular tail fluke. As members of the toothed whale suborder Odontoceti, sperm whales have large cone-shaped teeth that line their narrow lower jaw and weigh about 1 kg each. There are around 52 teeth on the lower jaw. However, the teeth from the upper jaw rarely break the gums.

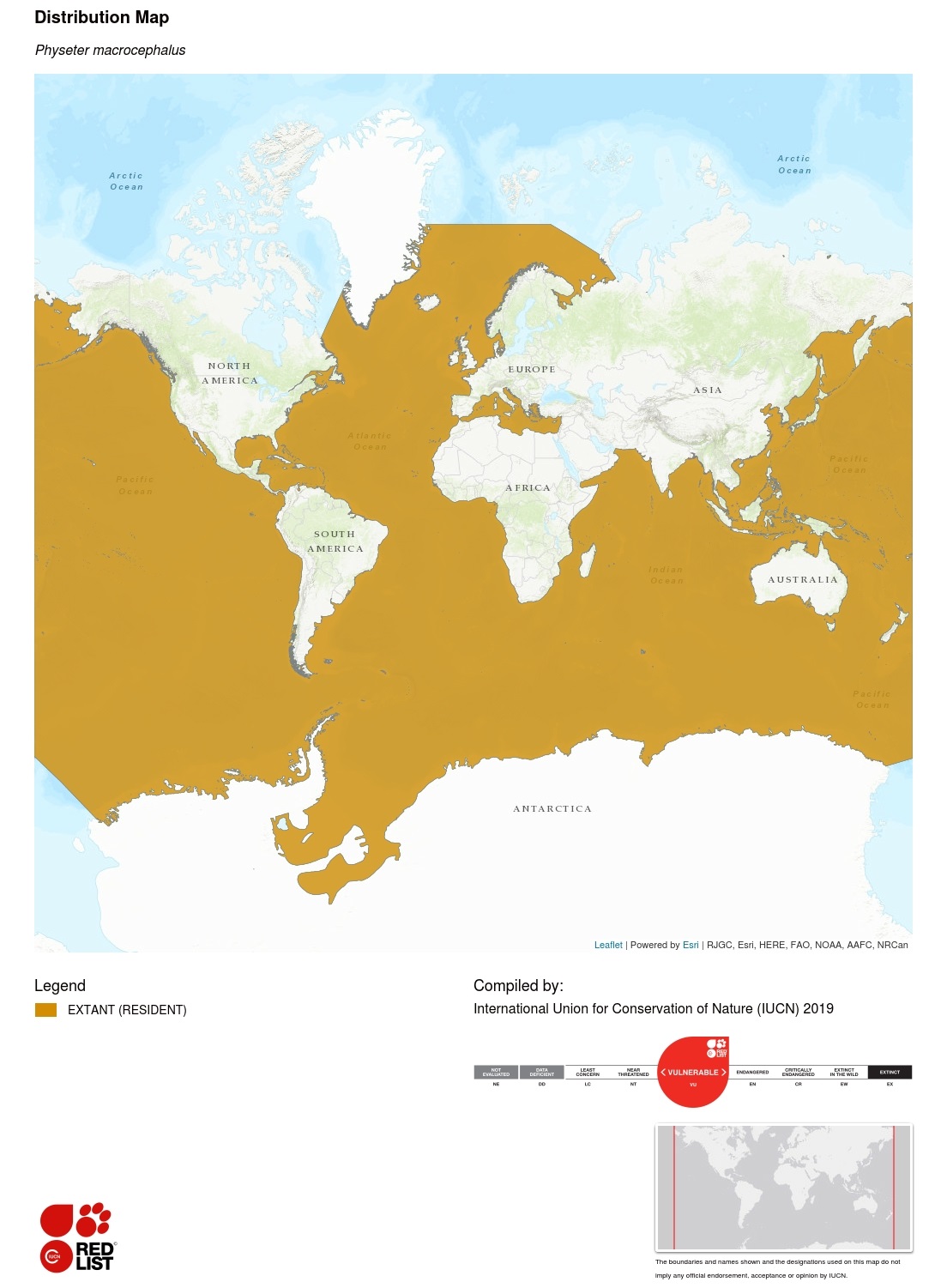

Distribution

As the marine mammal with the widest distribution, the sperm whale is found throughout the world’s oceans. They hunt in deep water, leading them to spend most of their lives farther offshore, away from coastal areas. However, the migration of sperm whales is not as well understood as that of baleen whales, and it is very unpredictable. It is believed that the migration patterns change depending on the whale's life stage, with juvenile whales not undergoing the same migration as the adults.

Reproduction and Development

The development of male and female sperm whales differs greatly. Male sperm whales reach sexual maturity by 20 and continue to undergo puberty until their late twenties. Only then do they begin to participate in reproductive behaviours with receptive females. Conversely, females reach sexual maturity at around nine years of age, when growth slows, and they begin to calve every five to seven years. After 14–16 months of gestation, a single calf of 3.5 m and 1,000 kg is born. These calves can eat solid food within a year, although they continue to nurse for several years. Sperm whales can live up to 60 years. Females will reach physical maturity at around 30 years, whereas males may continue to grow until 50. This often results in males growing much larger than females.

Behaviour

Sperm whales will form highly sociable groups centred on females, their relatives and their offspring. The groups are called “nursery schools” and allow the females to look after their young collectively and protect them from predators such as sharks and orcas. Males will participate in the schools until between the ages of four and 21, when they leave to join a herd of other bachelors. The young males will remain in bachelor herds until around 30, when they separate from the herd and begin migrating alone. The mature males will migrate farther north than female groups and only rejoin for the winter breeding season in the tropics.

Diet

Diving into the deep ocean to hunt for prey takes up much of a sperm whale’s life. They can dive up to 3 km deep and hold their breath for 120 minutes, though 45 minutes is the average. After dives, they spend time at the surface recovering before diving again. Their preferred food is giant squid. To hunt giant squid in the ocean’s depths, sperm whales use echolocation to navigate in the dark. Giant squid sometimes fight back, leaving scars on the sperm whales. Other easier prey includes smaller squid, octopus, fish, crustaceans and deep-dwelling sharks. To withstand these deep dives, sperm whale bodies are uniquely developed. Diving to such depths necessitates elevated concentrations of oxygen-carrying proteins in their bloodstream, bringing more oxygen to their muscles. Their ribcage is also collapsible, which allows their lungs to be compressed by the pressure of the dive. These dives can result in over 250 atmospheres of pressure.

Whaling

The spermaceti found in the sperm whale's head was the primary cause for the hunt of these giants. It was used in oil lamps, candles and more. Because of this dependence on spermaceti, sperm whales were the primary target of whaling from 1800 to 1987, which nearly decimated the sperm whale population. Due to the prolonged threat of whaling to sperm whale populations, the species has yet to recover fully.

Threats and Conservation

Sperm whales are listed as vulnerable by the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of Threatened Species; however, the Atlantic population was deemed not at risk by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada in 1996. Despite the end of whaling in 1987, many other human activities still threaten sperm whales. Pollution can harm their health and fertility. Entanglement in fishing gear can cause drowning. Vessel strikes, to which they are more prone because they spend a long time at the surface between dives, can lead to injuries and even death. Increasing amounts of evidence also point to noise pollution negatively impacting marine mammals. The noise may displace them from their preferred habitat, increase their stress levels, cause changes in their song and decrease foraging behaviour. When the noises are too loud, this can result in permanent or temporary hearing loss for these whales.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom