This November, The Canadian Encyclopedia is republishing the Stories of Remembrance, a 2005 project of our parent organization Historica Canada (formerly the Dominion Institute), Postmedia News (formerly CanWest News Service), and Veterans Affairs Canada.

The Stories were first published 10 years ago, on the 60th anniversary of the end of the Second World War. They examine the wartime memories or family connections of 13 famous Canadians — Farley Mowat, Arthur Hiller, Alex Colville, Marc Garneau, Lynn Johnston, Mike Myers, Catriona LeMay Doan, Vera Frenkel, Mary Walsh, Paul Gross, Chris Hadfield, Norman Jewison and John Ralston Saul — each of whom offers an insight on war, remembrance and Canada's place in the world.

In this exhibit, the Stories are briefly excerpted and organized into themes, ranging from the raw horror of battle, to the now-forgotten sense of purpose and confidence that empowered Canadians in the aftermath of the Second World War.

The Dogs of War

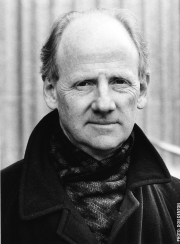

FARLEY MOWAT went to war in 1942 brimming with bravado and patriotism. Two years later he was a changed man, broken in spirit by what he had seen.

"The Second World War was the single most important element in my existence," he said. "It was a turnaround point in my life. It gave me clarity that I otherwise might never have acquired.

"I saw my own species behaving in a way that no other living creature would ever duplicate. It made me consider that perhaps we weren't the greatest form of life on Earth, not the absolute work of God, but perhaps some kind of cosmic joke, and a rather devilish one at that."

Mowat — whose later books were deeply influenced by his wartime experience — spent months in combat as an army officer in Italy in 1943. By 1944, he was the sole surviving officer in his regiment, among those who had landed on the beaches alongside him in the invasion of Sicily.

Later in life, Mowat's views on remembrance were uncompromising and controversial, rooted in the violence and horror he witnessed in Italy. He eschewed what he called the glorification of war in many Remembrance Day events. He said the media have elevated war into an act of heroism and prestige.

His feelings were first summed up in a letter he sent home as a young soldier from Italy, asking his parents to give a message to the family's beloved mutt, Elmer.

"Tell him from me," he said, "the Dogs of War aren't what they're cracked up to be."

(Farley Mowat died in 2014, aged 92.)

ARTHUR HILLER also experienced the horror of war, but he came away with a very different view of remembrance. Before he became a Hollywood film and television director, Hiller served in the Second World War as a navigator with the Royal Canadian Air Force, flying night-time bombing raids over Germany.

It was Hiller's job to get his six-man crew and their aircraft, nicknamed Li'l Abner, safely to its daily target and then home again — through treacherous weather, enemy searchlights, anti-aircraft fire, and German fighter planes.

Yet Hiller's worst memory of the war occurred not over Germany, but on the airstrip in England.

"Our Li'l Abner had been taken from us and given to another squadron," he says. "We all felt badly because we'd made 17 raids in that plane. It was our friend.

"A couple of days later we were standing on the airbase watching Li'l Abner going down the runway — being flown by another crew — and one of the tires blew out on takeoff. The wing then hit the ground, half the bomb load exploded, and everybody on board except the rear gunner was killed. "We had to clean the runway up afterwards, picking up the body pieces of our friends.

"Today, that still stays with me."

Decades later, Hiller believes remembrance serves a vital purpose.

"I think many young people don't know what World War Two was, or what went on there. If you ask people what the Holocaust was, there are many who don't know what you're talking about. It's just too far in the past.

"That's why we really need Remembrance ceremonies and other events like that. It lets us look back and see how things were at another time, to keep us alert, to prevent the same thing from happening in the future."

Appreciating the Peace

ALEX COLVILLE'S celebrated painting career got started in 1944, as a war artist amid the mud and fear of war-torn Europe.

Among the horrors he saw, none were as severe as the Nazi death camp in Bergen-Belsen, where Colville arrived just days after its liberation. He remembers great fields of open graves "with six or seven thousand people in them."

Colville believes the war left him with an acute awareness of time, and its fleeting presence in people's lives.

"The experience of a war, where you see so many dead, rather sharpens that sense," he says. "Like many people of my generation I think I have a sharpened sense of what it is to be alive.

"And to those of us who had been in the Second World War, many of life's most basic, bourgeois things — like having a job, a house, a car, children, a dog — those became precious things.

"My wife and I almost always go to the Remembrance ceremonies on November 11," says Colville. "You see, these are just ordinary people we're commemorating. Whether they worked at a grocery store or whatever, they were just ordinary guys who had gone to high school, joined the Army, and then went to war. I do very much admire them — the extraordinary things they did."

MARC GARNEAU knows nothing of war. Yet he believes that Canadians who lived through the First and Second World Wars learned lessons that are difficult for many to grasp today — about the fragility of peace and the wonders of a free society not threatened by fear or violence.

Decades of such good fortune, says the former naval officer and astronaut, have obscured these insights and turned the country's wartime past into a mere "abstraction" for many Canadians.

Garneau's grandfather, Colonel Gérard Garneau, was wounded twice during the First World War at Passchendaele and Lens. His father, Brigadier General André Garneau, was a career infantry soldier who fought during the Second World War across France, Belgium, Holland and Germany.

"I think we demonstrate respect and care for our veterans on Remembrance Day," he says. "But you know, if you ask people about the fact that we lost 60,000 Canadians in the First World War, and that we made similar contributions in the Second World War, it's abstract to a lot of them. They don't realize just how much effort and sacrifice went into that."

Family Ties

LYNN JOHNSTON, author of the comic strip For Better or For Worse, grew up in Vancouver, surrounded by stories of the Second World War. Her parents, Mervyn and Ursula Ridgeway, had met while serving together on the ground crew of a Royal Canadian Air Force bomber squadron in Britain.

"My parents talked about the war all the time," she says. "My dad especially — because it was the most exciting time in his life, when he really meant something to the world, when he was part of something big."

A watchmaker from Collingwood, Ontario, Mervyn enlisted in the Air Force at 18 and served as an aircraft mechanic at an airbase in Linton, England. Ursula left her home in West Vancouver at 19 and worked at Linton as a supply clerk, ordering nuts and bolts and other parts for the airplanes.

Johnston's parents never knew the fear of actual combat or the horror of battle, but they lived with the constant sorrow of seeing their friends die — or the anxiety of not knowing, each time an aircraft took off, whether its crew would return.

She says her parents maintained a deep respect for the war's veterans and their sacrifices, long after they came home to Canada.

"Dad went to every Remembrance Day parade. I think the loss of some of his good friends never, ever went away. I can remember going with him as a child to the cenotaph in North Vancouver, and my father standing there at attention with tears in his eyes."

MIKE MYERS, a.k.a. Austin Powers and the voice of Shrek, turns out to have a serious creative side, one that for many years has harboured dreams about making a thoughtful Second World War movie.

“I have attempted a screenplay about the Battle of Britain,” said Myers in 2005. “I don’t like war — who does? But the genre of the war movie is something that I’m fascinated with."

Myers's passion for the subject developed in the company of his parents, Eric and Alice, with whom he grew up in the middle-class Toronto suburb of Scarborough.

The couple had emigrated from England in 1955, and in Canada they raised their children in an atmosphere of staunch British pride. The story of the Second World War — particularly the English sacrifice — was, says Myers, “a huge part of what was talked about at the dinner table.”

Eric left his home in Liverpool and joined the British Army at 16. He served as a “sapper,” or private, with the Royal Engineers, building trenches, erecting bridges and clearing minefields on the front lines of the war in northwest Europe.

Alice joined the Royal Air Force during the war, working at radar stations in the south of England.

“Both my mom and my father were very respectful of the higher purpose of fighting the bad guys,” he says. “They called it ‘fighting the fascists.’ It was a big thing for them, they really believed in the cause.

“That spirit of saying no to bullies is something I have tremendous respect for. I have enormous gratitude to the World War Two generation, and I would like to think their sacrifice is never forgotten."

CATRIONA LE MAY DOAN always figured she was the family member who brought home the fancy medals. After all, she'd won two Olympic golds plus an armful of medals as a world champion speed skater. Then, in 2003, she learned for the first time about the wartime service of her great-uncle, Walter Le May, and a very different kind of medal he won back in 1944.

A Scottish navigator with the Royal Air Force during the Second World War, he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross after he and his crew discovered the location of several German defences while flying reconnaissance missions over Normandy prior to the D-Day invasion.

Le May Doan had never known about her ancestors' military connections until 2003, during a family visit to Scotland, when her uncle showed her his medal.

The DFC — a small, ornate silver cross, awarded for "acts of valour, courage or devotion to duty whilst flying in operations against the enemy" — inspired in Le May Doan a new interest in her family's long legacy of military service.

Her grandfather, Walter's brother, served in the Scottish Home Guard during the Second World War.

A second brother also flew for the Royal Air Force, and both he and Walter had trained in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan, as part of the 131,000 airmen schooled for the war in Canada by the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan.

Le May Doan's mother also lived through the war, growing up in Glasgow, Scotland, during the Blitz.

"I've discovered a lot of this family history quite recently, and it's pretty fascinating," she says. "It's hard to imagine here in Canada — this little bubble world that we live in — where we have so much freedom, and so much stuff. Yet at one time for my family, the war was real."

The Power of Memory

VERA FRENKEL thinks an army of archivists, armed with nothing more than microphones and tape recorders, should be dispatched to Legion halls and living rooms across Canada to capture the voices and memories of the country's surviving war veterans.

"I have a great respect for oral history," says the celebrated Toronto artist. "There should be a program in Ottawa, and every other city in the country, of recording [veterans' stories], so that we hear their voices and their memories . . . if one generation goes mute, the next generation can't hear them."

Vera Frenkel was an infant in 1939 when her Jewish parents fled the Nazis in Czechoslovakia at the start of the Second World War. Most of her aunts, uncles and extended family decided not to flee, and all died in concentration camps as a result. Growing up in England, and later in Montréal, Frenkel says her parents rarely spoke about the Holocaust.

"That whole generation had difficulty talking about what they'd lost and experienced, partly because it was too painful to relive it, and also because they wanted our generation not to be traumatized by it," she says. Yet that silence, says Frenkel, still wound itself "like a thread of grief through our lives."

Frenkel says Canada's aging veterans must tell their wartime memories, not just to their families, but to their country, if remembrance is to have any real meaning after they're gone.

"It's very hard to commemorate war," she says. "It's a tightrope no matter which way you look.

"But I would like to hear those voices. If that's done in any significant way, then we'd have a 'weather-front of memory' — an entire generation marking its moment in history."

(See The Memory Project.)

In MARY WALSH’s corner of the country, November plays only a supporting role in the annual ritual of wartime remembrance. The real commemorations — the genuine acts of tribute and sadness — take place in Newfoundland and Labrador on 1 July, when the rest of Canada is having a party and setting off fireworks.

"July 1 is a very strange holiday for us," says Walsh, the St. John's actor and comedian. "To the rest of the country it's Canada Day, but to us it's the Battle of Beaumont Hamel. Traditionally, it's a very sombre occasion."

On 1 July 1916, the Royal Newfoundland Regiment was wiped out on the opening day of the wider Battle of the Somme. Of 780 men who attacked German trenches outside the village of Beaumont Hamel, 684 became casualties — including Walsh's uncle.

"I guess everyone had someone they knew who fought or died there," she says. "The story of Beaumont Hamel is to Newfoundland what Gallipoli is to the Australians."

So visceral was the effect on Newfoundland, says Walsh, that until recently, some families still maintained a shrine in their homes to a grandfather or great uncle who braved the bullets at Beaumont Hamel.

"I remember travelling around Newfoundland with a theatre company in the 1970s," she says, "and there were places on the Northern Peninsula where families still kept their grandfather's uniform and medals and puttees, the whole bit, displayed on a kind of altar in their homes. It was a kind of art piece, really."

"We have to remember what we did. We will always have war, I guess. And we hope that by telling the stories of past wars, past bloodshed and past horror, that we could maybe learn to avoid it."

PAUL GROSS was only 15, out fishing one day with his grandfather, when the First World War intruded on his consciousness and ignited the fires of a lifelong obsession. Private Michael Dunn, his maternal grandfather, had fought for Canada in France and Belgium. But it wasn't until decades later, on a lake in Alberta with his grandson Paul, that he opened up about his haunting memories.

"I had always had questions — 'Did you kill Germans, did you bayonet people?' — and he'd always brush them off. But this day for some reason he started to talk. He told me a story of being on patrol with a small group of guys in a village. They encountered a German machine-gun nest and there was an awful battle that went on for hours, until virtually everyone was killed in his outfit.

"I'll just never forget it. It was one of those moments when this door opens on adulthood — you can suddenly see that there are mortal consequences to life — and I think it's because of that that I've wanted to do something about the war."

Gross, the actor and creative force behind two Canadian war films — Passchendaele (2008), and more recently, Hyena Road (2015) — says his fascination with military history stems not from a jingoistic romance, but a genuine concern with history and memory. Like it or not, says Gross, war is a central feature of human history, and any society that fails to understand its military past does so at its peril.

"There is a way of celebrating, honouring and being proud of our military service and our warriors without turning it into a pantheon of Greek gods. We should honour and respect what those men did for us. We sell ourselves short, and we do ourselves and our nation's history a great disservice, if we ignore it."

Thanks to Them All

Long before he rode rockets into space with NASA, CHRIS HADFIELD flew risky fighter-jet missions for Canada, operating without a shred of fanfare on the shadowy front lines of the Cold War. He was posted in 1985 to Canadian Forces Base Bagotville, Québec, where his CF-18 squadron guarded Canadian airspace as part of its duties with North American Air Defence Command (Norad).

During his first night on standby in Bagotville, Hadfield and fellow pilots were scrambled to intercept a group of Soviet "Bear" bombers flying south through Canada, just off the coast of Labrador.

"At that time the Soviets were flying their long-range bombers into Canadian airspace for a couple of reasons. Sometimes they took shortcuts through Canada on their way to Cuba. Other times they came to practice their cruise missile launches on North America," says Hadfield.

"We were obliged to get to them before they could get to the line where they could release those things. So we would be scrambled in the middle of the night, in our armed CF-18s, to intercept them and see what they were up to."

Hadfield vividly remembers finding the enormous bombers flying high above the sea, their engines humming as they plowed through the darkness. Turning on his fighter's search lights, he lit up the Soviet planes and shadowed them through the early dawn hours until they had left Canadian airspace.

It was the first ever intercept of a Soviet Bear bomber by one of Canada's new CF-18 fighters — a feat Hadfield repeated seven more times for his country.

Today, says Hadfield, Canadian soldiers, sailors and airmen still carry out difficult, dangerous tasks for their country at home and abroad — work that mostly goes unreported and unheralded.

He says Remembrance Day should be a time to honour not only the risks and sacrifices of former military warriors, but today's military, too.

"I feel a personal debt of thanks to all the folks who are serving in the Canadian military around the world right now," he says. "I don't think they get thanked nearly enough, and they get put in some horrific positions, with responsibilities that far outstrip those faced in the regular, daily lives of ordinary Canadians."

Self-Sacrifice, Self-Confidence

NORMAN JEWISON built his career amid the glitter and abundance of Hollywood. Yet Canada's most famous film director came of age in a very different world of food rationing, self-sacrifice and austerity.

By the time Jewison was 13, the Second World War was underway and all of Canada had put aside personal dreams and pursuits in favour of public service.

"The whole production of the country, from food to material to clothing, everything was being built and focused toward the war," he says. "I've never seen a society so focused."

At 17, Jewison volunteered for the Royal Canadian Navy. The war was in its final months by the time Jewison made it to sea, working on a Canadian corvette, escorting merchant ships up the east coast from Maine to Newfoundland.

"I was disappointed that I never got to cross the Atlantic and shoot up some U-boats," he says.

Today, Jewison says Canada has lost the collective purpose and confidence that once galvanized the country during the war and energized it afterwards.

"[The Second World War] was when Canada really matured and found itself," he says. "I don't know whether sacrificing so many young men is a good way to find yourself, but I do think that we really stood up for what we believed in.

"Canada had a passion and a sense of purpose that I've never seen since. I look around today and I sense that people don't know who they are anymore.

"But look at what we've done in history, with so few people. Look at what we accomplished in that war.

"I think that's what we need again today — confidence in ourselves."

"Memory of war," JOHN RALSTON SAUL once wrote, "is such a delicate thing."

Best known as a political essayist, Ralston Saul might better be defined as the son of a D-Day soldier, godson of a decorated war hero from the Italian campaign, and close friend of innumerable Canadian veterans. He grew up in a military family surrounded by men like his father who fought and won the Second World War.

Ralston Saul acquired many values from such people, but he never once heard them speak about battle. Yet he knew enough while growing up to appreciate that his parents and their friends had been immersed in a momentous event of great national sacrifice.

Capt. William Saul had fought briefly in North Africa, then landed on D-Day as second-in-command of a company of Royal Winnipeg Rifles.

Before leaving England, Capt. Saul had met and married Beryl Ralston, the daughter of a family with deep roots in the British military. She served during the war in a women's regiment that drove army trucks and taught soldiers how to do the same. Afterwards, she moved to Canada with Saul.

The generation that helped defeat the Nazis was one of the most self-assured on the planet, secure in its identity thanks largely to a grand ethos of public service that helped produce the victory in Europe.

“My father's generation had been part of this great army, one of the great modern armies in history. They had enormous self-confidence. They landed on D-Day, they liberated countries, they were astonishing people, and they did it all together. So when they hear people today searching for Canada's place in the world, they look at them and say: 'What are you talking about? Don't you know who we are, and what we've done?’”

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom