Black Pride: from Garvey to Marley

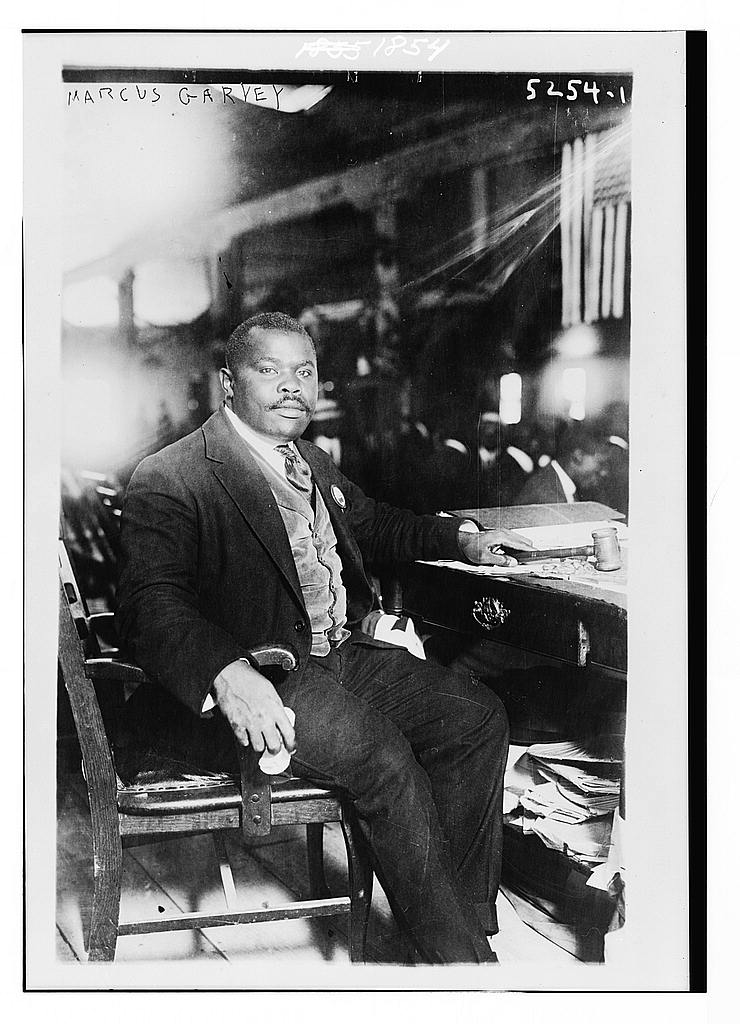

Marcus Garvey was a Jamaican civil rights leader of the early 20th century who promoted a new philosophy of Black nationalism, one that emphasized Black pride and called on the African diaspora to unite in Africa. To realize that dream, Garvey founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) in 1914. UNIA halls quickly opened around the world, including in Canada.

In 1930, Ras Tafari was crowned emperor of Ethiopia; an event many of Garvey’s followers in Jamaica believed was the fulfillment of his 1916 prophecy: “Look to Africa for the crowning of the Black king. He shall be the redeemer.” They formed a religion that saw Ras Tafari, also called Haile Selassie, as Christ reincarnated and took their name, Rastafarians, from his.

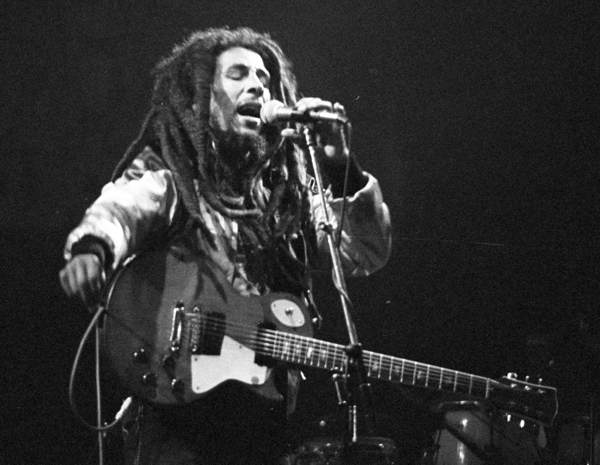

Bob Marley was born in in the same region as Garvey, in 1945, and rose from poverty to international acclaim. In the 1960s, he converted to Rastafarianism and often used language from Garvey and developed his Black pride philosophy. (In fact, Garvey often ended his speeches by crying out “One love!” Which many Marley fans will recognize.)

Marley was diagnosed with cancer in 1977, and it was during his sickness that he wrote “Redemption Song,” the final track on what would be his final album, Uprising. The song tells of a person abducted into slavery who is fighting for physical and mental freedom.

Marley read Black Man magazine, which is where he may have come across the speech Garvey delivered in Sydney, Nova Scotia, in 1937. He may have instead heard those lines spoken in general discussions of Garvey’s teachings. Regardless of the source, there is no question that Marley turned portions of that speech into the central lyric of “Redemption Song”: “Emancipate yourselves from mental slavery/None but ourselves can free our minds.” (See also Reggae.)

UNIA in Nova Scotia

Africans have been in Nova Scotia since its earliest days, when Mathieu Da Costa arrived with French explorer Samuel de Champlain in 1604. Free and enslaved Black people lived in Halifax when it was founded in 1749. By 1758, about 350 Black people from the West Indies were enslaved in and around Fortress Louisbourg (see Black Enslavement in Canada), and Black Loyalists fleeing the American Revolution settled in Birchtown in the 1780s.

In the early 1900s, the Dominion Iron and Steel Company recruited hundreds of people from the West Indies to work in Cape Breton (see Caribbean People). In 1918, the migrants set up one of Canada’s first UNIA halls in Glace Bay, Nova Scotia. The chapter was headed by Albert Francis, who had left Barbados in 1916. Other UNIA chapters were established in Sydney (1919) and New Waterford (1929).

By the 1930s, Garvey’s movement had dwindled and he had been deported from the United States. In 1937, he set out on what would be his final speaking tour. The Cape Breton UNIA members invited him to Nova Scotia, where he arrived in the fall to deliver public talks in Sydney and Halifax.

On 1 October, Sydney’s mayor introduced him to a full house at Menelik Hall. Garvey said he had long corresponded with UNIA members there, but was glad to meet them in person. He went on to deliver a speech on Black history and pride in Canada and beyond (see Black History in Canada). Garvey spoke well of his 1928 meeting with Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King at a League of Nations meeting. Towards the end, he spoke these lines:

We are going to emancipate ourselves from mental slavery because whilst others might free the body, none but ourselves can free the mind.

Mind is your only ruler, sovereign. The man who is not able to develop and use his mind is bound to be the slave of the other man, who uses his mind, because man is related to man under all circumstances for good or ill. If man is not able to protect himself from the other man, he should use his mind to good advantage.

The speech was printed in Black Man, a magazine edited by Garvey and that also published a speech he delivered to the residents of Africville on 7 October 1937.

While many UNIA halls closed in the years following Garvey’s death in 1940, Cape Breton’s stayed open. The Glace Bay hall was restored in 2003 and it re-opened in 2006 as the UNIA Cultural Museum. Every year in mid-August, about the time of Marcus Garvey’s 17 August birthday, people gather to celebrate Marcus Garvey Days in Cape Breton. Through song, dance, history and business classes, the celebration continues the work of Garvey.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom