The Last Spike was the final and ceremonial railway spike driven into the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) track by company director Donald Smith on the morning of 7 November 1885. The ceremony marked the completion of the transcontinental CPR and was a muted affair at which a group of company officials and labourers gathered at Craigellachie near Eagle Pass in the interior of British Columbia. One of about 30 million iron spikes used in the construction of the line, the Last Spike came to symbolize more than the completion of a railway. Contemporaries and historians have viewed the Last Spike — as well as the iconic photographs of the event — as a moment when national unity was realized.

The Last Spike Ceremony

By November 1885, work crews laying track for the CPR from the west and the east had converged at Eagle Pass in the Monashee Mountains west of Revelstoke, British Columbia. CPR officials decided that, after five years of construction, some sort of ceremonial completion of the line should take place. However, the company could only afford, and only wanted, a modest celebration. There were no reporters present and no politicians. Company president George Stephen was in England and unable to make the trip. In his stead, general manager William Van Horne and director Donald Smith travelled to BC. They were joined by, among others, surveyor and company director Sandford Fleming and Major Albert Bowman Rogers, who suggested the CPR cut through the Selkirk Mountains at Rogers Pass.

As the morning of 7 November dawned, these officials — along with some of the workers who had completed the track only the night before — gathered at the western entrance to the mountain pass, at a spot Van Horne called Craigellachie. The name was in honour of a Clan Grant gathering place in Scotland that both George Stephen and Donald Smith grew up near; Smith was a member of Clan Grant (see Scottish Canadians). At precisely 9:22 a.m., an iron spike (used to fasten steel rails to wooden railway ties) was positioned, and Smith raised a hammer to strike the first blow. His aim was off, and the spike bent. It was replaced by another, and on his second attempt Smith succeeded in driving it home. The small crowd raised a cheer, and locomotive whistles blew.

When asked to say a few words, Van Horne simply declared, “All I can say is that the work has been done well in every way.” That afternoon, he telegraphed Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald to say, “Thanks to your far seeing policy and unwavering support the Canadian Pacific Railway is completed. The last rail was laid this (Saturday) morning at 9:22.”

The official train carrying Van Horne and the other dignitaries steamed across the newly laid track on its way down to Port Moody, on Burrard Inlet — at the time, the designated western terminus. It was the first train to cross the completed CPR from coast to coast.

The Spikes

There are actually four Last Spikes. Governor General Lord Lansdowne had planned to attend the ceremony, bringing with him a silver spike prepared for the occasion, but he was called back to Ottawa on business. Lansdowne later mounted the ceremonial spike on a granite base and gave it to Van Horne. In 2012, Van Horne’s heirs donated the relic to the Canadian Museum of Civilization (now the Canadian Museum of History).

Donald Smith received the bent spike as a memento and later had pieces of it fashioned into decorative pins. This misshapen spike remained in Smith’s family until 1985, when his great-grandson donated it to Canadian Pacific, which in turn presented it to the National Museum of Science and Technology (now the Canada Science and Technology Museum). The iron spike that Smith successfully drove into place was pulled out following the ceremony to discourage souvenir hunters. It eventually ended up in the CPR president’s office in Montreal, from where it disappeared in the 1940s. It was exchanged for a fourth spike, which remained in place.

Some believe that the missing spike fell into the hands of a Canadian patent officer in Ottawa, who passed it down to his children. At some point, it was fashioned as a silver-plated handle to a carving knife and is said to be stored in a safety deposit box in Winnipeg. David Morrison, director of archeology and history at the Canadian Museum of Civilization told the Globe and Mail in 2012: “There is a plausible line of provenance [about the Winnipeg spike]. It seems like a reasonable conclusion to make. You just can’t be 100 per cent sure and that is very often the case.”

Photographs of the Last Spike Ceremony

It is sometimes said that the photographs of the event are the most famous or iconic in Canadian history. They were taken by Alexander Ross, a Calgary photographer, who happened to be on site and was pressed into action when the expected photographer, Cornelius Soule, did not arrive. The photographs became almost instant classics. The CPR disseminated reproductions of them widely, and by 1924, historian R.G. MacBeth, in his book about the railway, was suggesting that there should be a copy of a Last Spike photograph on the wall of every schoolroom in the country because it captured “the birth of a nation.”

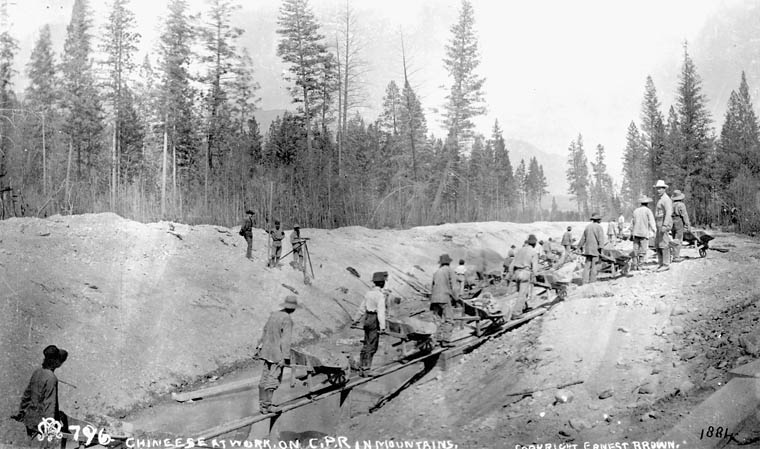

Some 15,000 Chinese labourers helped build the CPR — in particular the section in British Columbia — working in harsh conditions and for half the pay of their White co-workers. No Chinese labourer is present in any of the iconic photographs of the Last Spike ceremony. (See also The “Other” Last Spike.)

The Craigellachie Kid

The famous photographs of the Last Spike ceremony depict such historic figures as CPR director Donald Smith (driving the spike), CPR general manager William Van Horne (behind Smith’s right shoulder) and Sandford Fleming (with white beard and wearing a top hat). Standing directly behind Smith is a young man named Edward Mallandaine, who is sometimes referred to as the Craigellachie Kid. Mallandaine was 18 years old when the photo was taken. He had just arrived at Craigellachie the night before and pushed his way to the front of the crowd during the ceremony, appearing at the centre of the iconic photographs.

Before the Last Spike ceremony, Mallandaine had quit school in Victoria, BC, to join Canadian forces fighting to put down the North-West Rebellion. Arriving too late to join the conflict, he headed back west, where he started his own business in the summer of 1885, delivering newspapers and supplies by pony between Eagle Pass and Farwell, BC.

A few years after the Last Spike was driven, Mallandaine helped establish the town of Creston, BC, on Kootenay Lake.

Significance and Legacy

The hammering of the Last Spike is regarded as one of Canada’s most symbolic events. Even though William Van Horne insisted that the CPR “was built for the purpose of making money for the shareholders,” and was not a nation-building exercise, the idea that the railway made Canada possible by joining the two ends of the country has been an enduring one. The Newfoundland poet E.J. Pratt wrote a book-length poem about the railway, Towards the Last Spike, which won a Governor General’s Award in 1952 and which depicts the railway as a force for national unity. In his two-volume history of the construction of the transcontinental line, Pierre Berton coined the phrase “national dream” to describe the railway, which he portrayed as a heroic endeavour without which Canada would not exist. If the argument is accepted that the railway created Canada by spanning the continent, the Last Spike was the symbolic moment of the country’s completion.

(See also Railway History.)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom