Founded in 1883, the Trades and Labor Congress of Canada (TLC) was the first union central to take lasting root in Canada. Principally bringing together craft unions, the TLC was the largest workers’ organization in Canada at the turn of the 20th century. The TLC saw its membership fluctuate in the 20th century because of the fierce competition between national and international unions and the rise of industrial unionism. In 1956, the organization merged with the Canadian Congress of Labour to become the Canadian Labour Congress.

Founding and Expansion

In December 1883, the Toronto Trades and Labor Council (TTLC) convened the various workers’ organizations in Toronto to discuss the creation of a Canadian union central. The negotiations, which took place under the direction of Charles March, president of the TTLC, did not immediately address the creation of a permanent organization. Following the example of the defunct Canadian Labor Union (1873–77), the approximately 50 delegates were in favour of a program of political reform. It was not until the second assembly, in 1886, that the new organization’s structure took form. The TLC’s objective was “to rally all the workers’ organizations to work to fashion new laws or amend existing laws, in the interests of those who must earn their living, while ensuring the well-being of the working classes.”

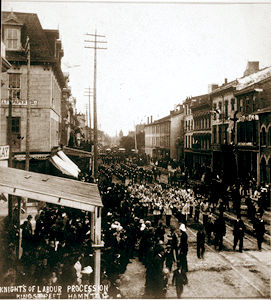

Largely dominated by the Knights of Labor, the TLC initially brought together unionists from Ontario, but gained national stature in the following decade when it founded legislative committees in Manitoba (1896), British Columbia (1896) and New Brunswick (1899).

These branches of the TLC engaged in political lobbying. To this end, the TLC organized meetings with politicians and sent an annual briefing to the authorities setting out the resolutions adopted by the congress. In 1898, for example, its program of reforms included mandatory free instruction, an eight-hour working day, governmental inspection of all industries, public ownership of utilities, the abolition of the Senate, the prohibition of work by children under 14 years of age and the abolition of prison labour.

Splitting

The TLC faced major disagreements, however, between those who advocated for its integration into American union structures and those wishing Canadian unions to have greater independence from their counterparts to the south. Its meagre financial capacity prevented the TLC from hiring full-time organizers, and its bylaws restricted some local unions from joining. Delegates went so far as to question the utility of this “workers’ parliament”.

On the ground, international unions affiliated with the American Federation of Labor (AFL) were engaged in a battle with the Knights of Labor to recruit workers to their cause. The TLC became the arena for these clashes in 1902 when the assembly held in Berlin (Kitchener), Ontario, expelled all unions that had concurrent jurisdictions with respect to those of the international unions. Several assemblies of the Knights of Labor were among the 23 unions that were expelled. These unions went on to form their own rival organization: the National Trades and Labor Congress. This ended the quasi-hegemony the TLC held over the Canadian union movement. Subsequently, the TLC was fragmented by national unions, by openly socialist and unionist organizations, and by the rise of industrial unionism.

Despite these internal squabbles, the TLC pursued its mandate of political representation. Pressed by delegates from British Columbia and Manitoba, the TLC reviewed its commitment to political activism at the turn of the 20th century, the era during which the first workers’ political parties were established. In 1906, the TLC endorsed the creation of a workers’ party following a debate between the reform and the socialist factions of the organization. Some of the TLC’s leaders, such as Ralph Smith and Alphonse Verville, ran for office.

New Rifts, Renewal and Decline

In 1919, suffering from political tensions that were tearing it apart, the TLC experienced a crisis that saw the socialist and industrialist unionists abandon it to form the One Big Union (see Revolutionary Industrial Unionism). Nonetheless, after the setbacks sustained by the industrial unionists during the massive wave of strikes in 1919, the TLC emerged as the leading union central. In 1924, the organization’s membership was more than 200,000 strong. However, the slowdown in unionization between 1920 and 1924 cost the TLC close to 50,000 members.

The TLC then had to confront the new momentum of industrial unionism led first by the Workers Unity League and later by the Committee for Industrial Organization. The latter organization was founded in 1935 and became the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) in 1938. Once again, infighting in the United States between loyalists of the AFL and of the CIO forced the TLC to reluctantly expel the CIO unions from its ranks in 1939. Along with the All-Canadian Congress of Labour, the unions that were expelled from the TLC formed the Canadian Congress of Labour (CCL) in 1940. This organization became the main union central in Canada thanks to burgeoning industrial unionism during and immediately after the Second World War.

After a witch-hunt against communists in both union centrals in the late 1940s and early 1950s, and after the 1955 merger of the AFL and CIO in the United States (see AFL-CIO), the CCL and the TLC united in 1956 to form the Canadian Labour Congress.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom