“The war was over […] and I was in this trench in Holland,” said Second World War veteran Louis Curran. “After all the noise, all of a sudden, it became very quiet. No noise, no more firing, no more cannons, no more guns.”

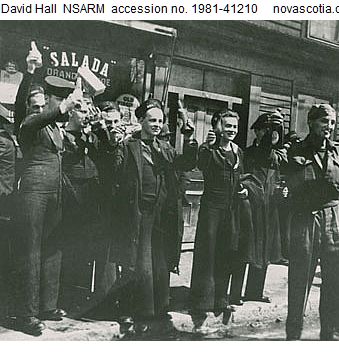

After the bombs were silenced in Europe, a blast of cheer shot through the home front. Victory in Europe — the official end to over five years of fighting — was celebrated on 8 May 1945, after Germany's unconditional surrender. In cities and towns across Canada, a war-weary nation expressed its joy and relief at the news.

In Halifax and Dartmouth, cities equally exhausted by their wartime role, celebrations erupted into looting and rioting — and were perhaps a reminder that the war was not yet over, as conflict with Japan was ongoing.

.

War in Europe

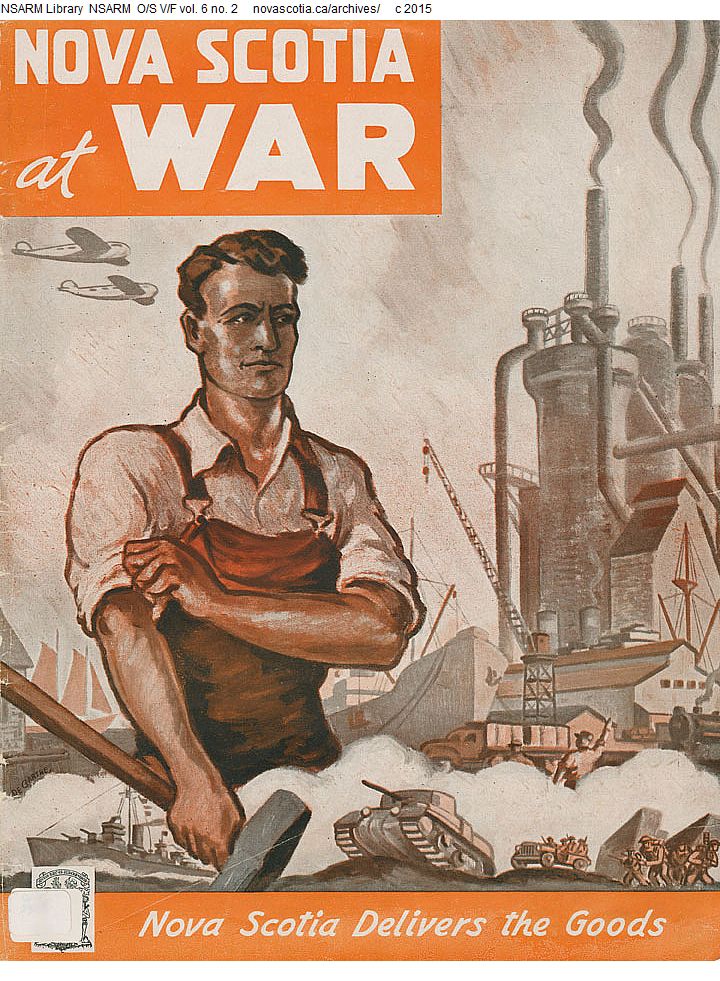

Canadians had been at war since September 1939 — retooling our factories, mobilizing our men and women, and sending our troops and resources overseas. Before the United States entered the fight, Canada stood beside Britain and the oppressed peoples of Western Europe, intent on defeating Nazi Germany and the Axis powers.

By the spring of 1945, the names Hong Kong, Dieppe, Sicily, Ortona and Juno were seared into the nation's memory — and in the psyches of families whose sons had fallen there. By this time, Canadians had also survived the U-boat menace off our shores in the North Atlantic, and were still engaged in the risky, deadly work of bombing German cities, and liberating Belgium and the Netherlands.

A million Canadians were in uniform; 42,000 had died and tens of thousands more were wounded or languishing in prisoner of war camps. The country was eager for victory and ready for peace. When news reached home on 7 May that Germany had surrendered, Canadians breathed a deep sigh of relief.

A day later, we celebrated.

How Canada Celebrated

The first Canadians to cheer the victory were the soldiers, sailors and airmen on the front lines in Germany, the Netherlands and the North Atlantic. Although the shooting had stopped, there was much work still to be done. Many would soon take up occupation duties and help with the urgent delivery of relief supplies to starving civilian populations. Their return home, however, was close at hand.

In Canada, people filled city streets and town squares. From Sydney, Nova Scotia to Surrey, BC, offices and schools emptied, and some factories shut down for the day, as Canadians gathered in vast crowds to laugh, dance, attend outdoor band concerts, cheer the men and women in uniform, and watch tickertape fall from the sky.

For others it was a day of thanksgiving. Canada was a country of faith in 1945, and everywhere people attended religious services to mark the day with prayer and reflection.

In Canada's East Coast naval port, however, the celebrations devolved into chaos and violence.

Halifax in Wartime

During the Second World War, Halifax was a bustling port city where massive transatlantic convoys carrying troops, munitions and supplies were assembled. As a result, the city’s population increased by nearly 60 per cent between 1939 and 1944 — nearby Dartmouth by 73 per cent — with temporary government and military jobs created to keep local war industries moving. All the while, tens of thousands of troops, airmen and sailors filed in and out of town.

Residents grew weary of the city’s transient population, and with good cause. According to one report, “vandalism, including the breaking of plate glass windows and the tearing down of awnings and street signs, mostly by intoxicated Naval ratings on paydays, was a usual and expected occurrence [in wartime Halifax].”

The RCN had expanded rapidly during the Second World War — from 3,500 regulars in 1939 to some 96,000 by 1945 — and personnel training suffered as a result, particularly “discipline ashore.” Over 18,000 Navy personnel were stationed in Halifax in May 1945.

For these reasons and more, Halifax was tense on VE-Day.

Open Gangway

Victory in Europe was announced the morning of 7 May 1945 on civilian radio in Halifax, and residents were given the rest of the day off. However, trouble started that evening after a fireworks display. “Open gangway” (i.e., a holiday) was declared for Navy personnel for reasons that remain unclear.

Navy signalman Frank O’Hara described how the Halifax riot started on a tramcar that night: “[sailors] kicked off all the passengers and the conductor and I guess one of the guys must have known how to use it or maybe it was pretty simple. In any event they went tearing down the street with this and so I followed, walked down the street because I figured they couldn’t go too long before they went off the tracks. Sure enough, at the first bend in the road, they went off the tracks. It didn’t tip over or anything.”

In possibly another incident (several tramcars were vandalized that night), sailors took over the driver's seat of a tramcar, smashed its windows and set it on fire. When firemen came to put out the fire, sailors disconnected their hose before cutting it with an axe.

Like Drunken Sailors

Open gangway continued the next day. Along with civilians, sailors overpowered guards at Alexander Keith’s brewery and passed out cases of beer to passersby. As crowds spilled downtown, window displays and store interiors were either vandalized, looted or both. People took whatever they could — including mannequins, with which they danced in the streets — but mainly clothes, jewellery and shoes (perhaps the most popular item).

Vandalism and theft aside, the general atmosphere in Halifax was described as convivial rather than criminal. Though in the end, downtown Halifax descended to mob rule. By 5 p.m., the mayor declared VE-Day over. But, as rioting subsided in that city, it was taken up to a lesser scale across the harbour in Dartmouth. A military curfew was set in force by 11 p.m. and the streets cleared.

Outcome

The Toronto Star front page on 9 May 1945 reported that “the [Halifax] business area looks like London after a blitz” and that two sailors had died (the official number was three), including one 18-year-old who “succumbed to over-intoxication,” one found on the Dalhousie campus and another “killed in the rioting.”

In the immediate aftermath, a Royal Commission was ordered on 10 May 1945. The report, filed by Justice R. L. Kellock, tallied the damages in both Halifax and Dartmouth. Over 200 people were brought up on charges (117 civilians, 41 soldiers, 34 sailors and 19 airmen), either for being in possession of loot, drunkenness, being AWOL or other reasons. A total of 564 businesses were damaged, 207 shops looted and 2,624 windows smashed.

The federal government provided just over $1 million in compensation to businesses affected by the riot. The Nova Scotia Liquor Commission alone received $178,924 in reparations.

After VE-Day

Despite Victory in Europe, the war in the Pacific continued. It would be three more months — until the United States dropped two atomic bombs on Japan in mid-August — before Japanese leaders surrendered. VJ Day (Victory over Japan) was celebrated on 2 September 1945, along with the official end of the Second World War.

Canada emerged from the conflict with one of the strongest military forces in the world, and an economy and society poised for decades of growth and prosperity. Our population was set to expand, with a baby boom, and throngs of war brides and new immigrants from Europe and elsewhere about to arrive on Canada's shores.

But the future was also uncertain: Fascism had been defeated, but a Cold War with the Soviet Union was coming, in which Canada would take up its role as an important middle power in both the NATO alliance and the United Nations. Within five years, Canadian troops would be in combat overseas again, in Korea.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom