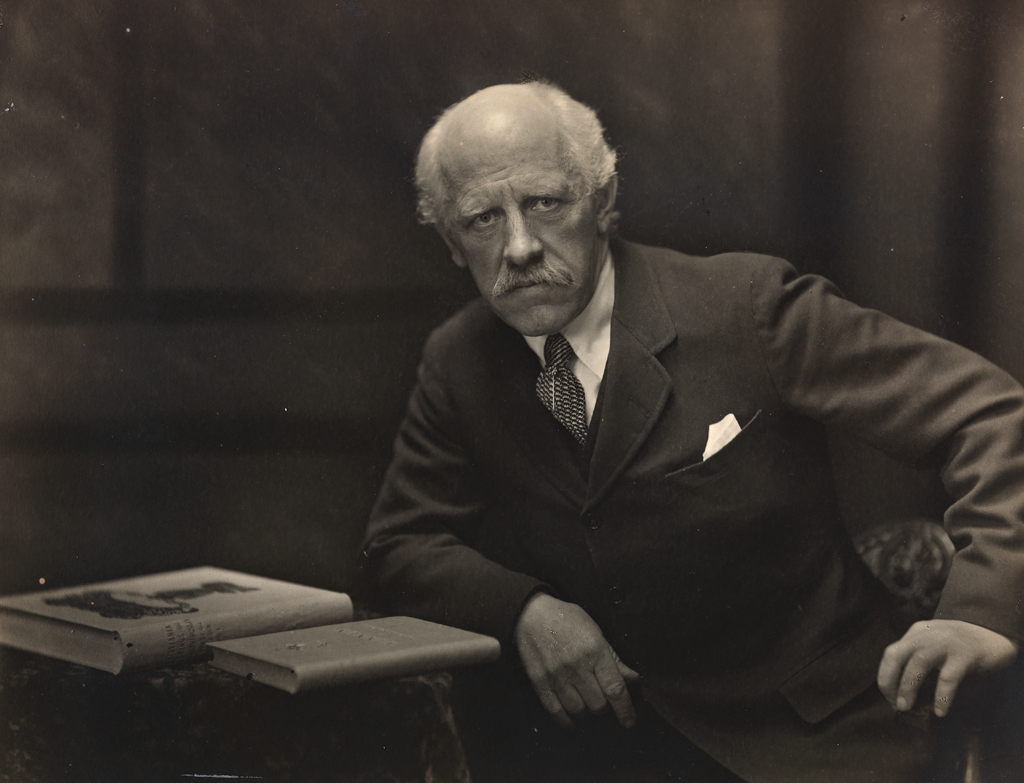

Otto Neumann Knoph Sverdrup, arctic explorer and author (born 31 October 1854 in Bindal, Norway; died 26 November 1930 in Bærum, Norway). Sverdrup led the second Fram expedition from 1898 to 1902 to the Canadian Arctic and claimed the Sverdrup Islands on behalf of the Norwegian Crown. Sverdrup’s voyage prompted a series of Canadian Arctic expeditions to defend Canadian sovereignty in the far north. Despite Sverdrup’s objections, Norway recognized Canada’s claim to the Sverdrup Islands in 1930.

Early Life

Otto Sverdrup was the son of Ulrik Frederik Suhm Sverdrup (1833–1914) and Petrikke Neumann Knoph (1831–85). He grew up on his parents’ farm in Bindalen, excelling at skiing, shooting and sailing. At 17, he began a career as a sailor, working on a series of American and Norwegian vessels. Sverdrup qualified as a ship’s mate in 1878 and a ship’s captain in the early 1880s.

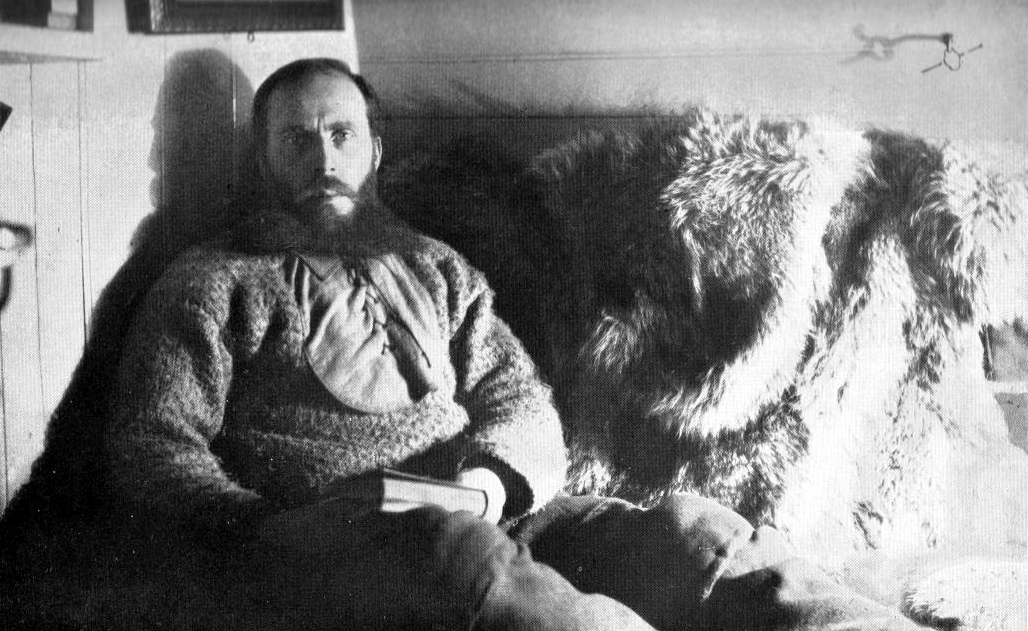

Voyages with Fridtjof Nansen

In 1885, Otto Sverdrup moved to Steinkjer, where his father had purchased a new farm. In Steinkjer, Sverdrup became friends with the lawyer Alexander Nansen, who recommended him to his younger half-brother Fridtjof Nansen to captain a planned voyage to traverse the interior of Greenland. In 1888, Fridtjof Nansen, Sverdrup, two other Norwegians and two Sami skied across Greenland from Umivik to Gothaab (now Nuuk) in six weeks, then spent the winter in Gothaab.

From 1890 to 1893, Sverdrup supervised the building of the Fram (Norwegian for forward), a specially commissioned ship designed to withstand the pressure exerted by arctic ice; the intent was to travel via arctic ocean currents while trapped in the ice. From 1893 to 1896, Sverdrup served as skipper of the Fram on Nansen’s voyage to the Arctic, remaining in command of the ship when Nansen and Hjalmar Johansen left the rest of the crew aboard in March 1895 in an effort to reach the North Pole by dogsled. The Fram remained encased in the ice until 1896, when Sverdrup successfully navigated the ship from Svalbard back to Norway, arriving home one week after Nansen.

Marriage and Children

On 12 October 1891, Sverdrup married his first cousin Gretha Andrea Engelschiøn (1866–1937) in Kristiania (now Oslo). Sverdrup renegotiated his wages at the time of his marriage to ensure his family’s financial security. Otto and Gretha had three children, Audhild (1893–1932), Otto (1897–1978), and Hjordis (1904–53).

Second Fram Expedition

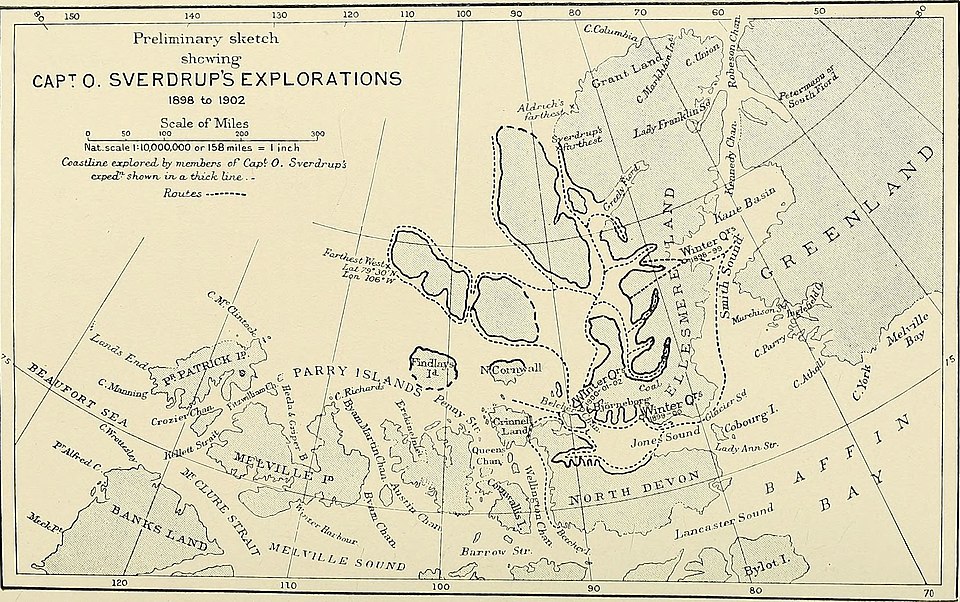

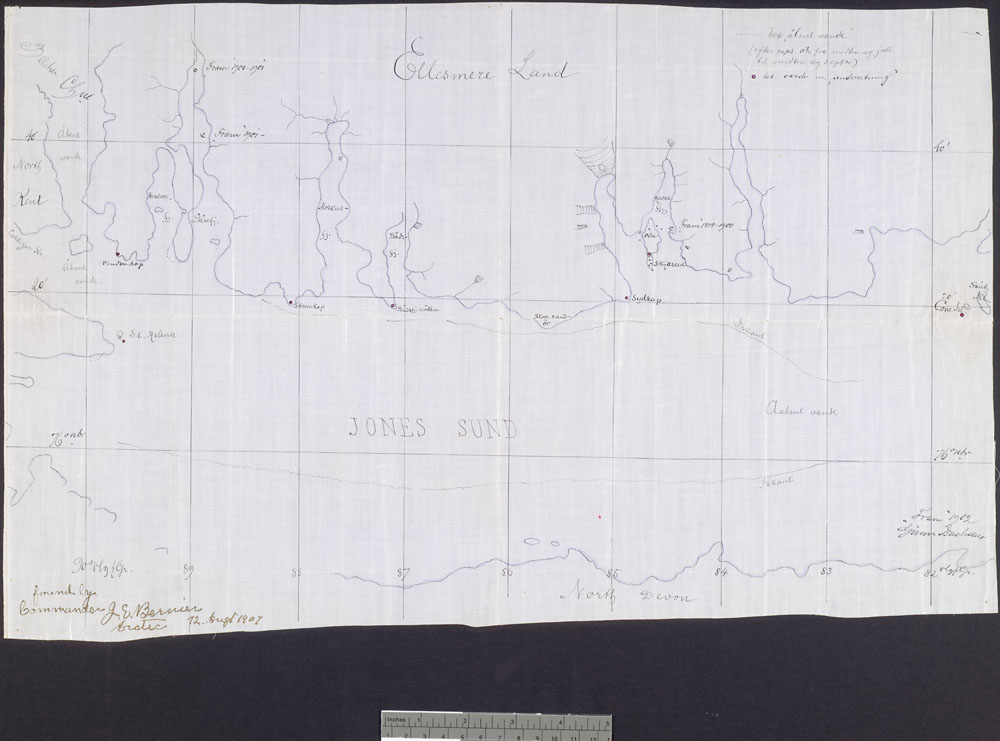

From 1898 to 1902, Otto Sverdrup led the second expedition of the Fram, which included five scientists and 10 crew members, to the Arctic islands north of the Canadian mainland. The initial goal of was to survey northern Greenland and explore the little known northern and eastern coasts, but Sverdrup encountered poor weather conditions as well as American polar explorer Robert Peary on a Greenland expedition in 1899. Instead, Sverdrup decided to sail to Jones Sound and the uncharted western coast of Ellesmere Island. The second Fram expedition was sponsored privately by Norwegian diplomat Axel Heiberg and Amund and Ellef Ringnes of the Ringnes Brothers brewing firm. The Norwegian government loaned Sverdrup the Fram and provided him with the funds to repair and alter the vessel.

The second Fram expedition mapped the previously uncharted western coast of Ellesmere Island, King Christian’s land and Devon Island, as well as a group of islands unknown to Europeans that Sverdrup named for his sponsors Axel Heiberg, Amund Ringnes and Ellef Ringnes. These islands became known as the Sverdrup Islands. Over the course of the voyage, Sverdrup and his team gathered 50,000 plant specimens and 2,000 animal specimens. The scientific research from the second Fram expedition was published in a series of five volumes. Sverdrup’s geological samples would later reveal the presence of oil and gas in the region, which increased the economic significance of the Sverdrup Islands.

Sverdrup Islands

Otto Sverdrup claimed the Sverdrup Islands for the Norwegian Crown. His book about the voyage, New Land: Four Years in the Arctic, concluded with the words, “An approximate area of one hundred thousand square miles had been explored, and, in the name of the Norwegian King, taken possession of.” In 1902, King Oscar II of Norway was also King of Sweden, and he showed little interest in incorporating the Sverdrup Islands into his territory. Norway achieved independence from Sweden in 1905, and the new, King Haakon VII, also appeared to have little interest in the Sverdrup Islands. Sverdrup wrote to the Norwegian foreign ministry in 1928 demanding that Norway either assert its claim to the Sverdrup Islands or the Canadian government refund the costs of the second Fram expedition.

Canadian Response

In 1880, Governor General Lord Lorne had received an order-in-council from the British government that ceded “all British territories and possessions in North America, not already included within the Dominion of Canada, and all islands adjacent to any of such territories or possession” except for Newfoundland, which would not join Canada until 1949. In 1895, Canada created the four provisional districts of Ungava, Yukon, Mackenzie and Franklin but otherwise made little effort to survey the Arctic islands in the late 19th century. Sverdrup’s claim that the Sverdrup Islands belonged to the Crown of Norway shocked Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier and prompted a series of Canadian nautical voyages to map the Arctic islands and assert Canadian sovereignty over the region. These expeditions included the 1903–04 voyage of the Neptune by geologist Albert Peter Low, and annual Arctic voyages between 1904 and 1911 by Joseph-Elzear Bernier, who established Royal Canadian Mounted Police outposts in the Arctic. (See also Canadian Arctic Expedition and Eastern Arctic Patrol.)

Later Life

In 1906, Otto Sverdrup purchased a plantation in Baracoa, Cuba. The plantation was not financially viable, and Sverdrup returned to Norway. In 1914, Czar Nicholas II of Russia commissioned Sverdrup to command the whaling ship Eclipse and search for the missing Russian arctic explorers Georgy Brusilov and Vladimir Rusanov. Sverdrup did not find the missing explorers, but he rescued the crew of two Russian naval transport ships trapped in the ice near Cape Tsjeluskin. During his last years, Sverdrup raised funds for the preservation of the Fram, which is now on display at the Fram Museum in Oslo.

Canadian Sovereignty

In 1925, Canada asserted its claim to the Sverdrup Islands through the sector principle, declaring that all land in the sector between Canada’s eastern and western borders and the North Pole belonged to Canada except for Greenland, which belonged to the Danish crown. In 1928, Norway renewed its claim to the Sverdrup Islands. Future Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson, then the first secretary in the Department of External Affairs, prepared a lengthy report titled “The Question of Ownership of the Sverdrup Islands,” which argued Norway had never occupied or administered the islands. On 11 November 1930, Norway recognized Canadian sovereignty over the Sverdrup Islands but did not recognize the sector principle. One week later, the United Kingdom recognized Norwegian sovereignty over Jan Mayen, a volcanic island in the Arctic Ocean east of Greenland.

Sverdrup opposed Norway ceding the Sverdrup Islands to Canada, and he received a financial settlement from the Canadian government. On 23 September 1930, the Canadian Undersecretary of State for External Affairs, Oscar Douglas Skelton, wrote to the British representative in Oslo, Sir Charles Wingfield, “We desire to arrange for the payment as early as possible to Commander Sverdrup of the grant of $67,000 made by the Canadian Parliament, conditionally on the reaching of a satisfactory agreement as to the title of the islands.” The settlement included the acquisition of Sverdrup’s maps, records and diaries of the second Fram expedition. Sverdrup died two weeks after Canada formally took possession of the Sverdrup Islands. Sverdrup’s papers were returned to Norway after the Second World War and are now part of the National Library of Oslo.

Legacy

Sverdrup received gold medals from the Norwegian Geographical Society (1889) and the Royal Geographical Society (1903). In his unpublished autobiography, Norwegian-Canadian Arctic explorer Henrik Larsen described Sverdrup as “the most competent and practical of all the Norwegian explorers of that era, but being both shy and reticent, he was satisfied with taking a back seat and was of course overshadowed by such men as Nansen and Amundsen.” The arctic survival techniques developed by Nansen and Sverdrup, informed by Inuit practices, were adopted by fellow Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen in his navigation of the Northwest Passage from 1903 to 1906 and expedition to reach the south pole in 1911.

In 1999, a joint team of Norwegian and Canadian scientists spent a year based on Ellesmere Island, retracing Sverdrup’s voyage as part of the Otto Sverdrup Centennial Expedition. In 1992, Norwegian tourist Asbjorn Astrom bolted elaborate metal plaques commemorating Sverdrup to boulders on Ellesmere Island, an action that was criticized by Canadian travel writer Jerry Kobalenko. In 2004, Canada, Greenland and Norway issued a rare joint stamp in honour of Sverdrup’s 150th birthday.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom