In late February 1913, a teacher at Montreal’s Aberdeen School called her Jewish students “dirty” and said they should be banned. News of the incident spread amongst the students, who decided to strike. Though threatened by school officials, the students succeeded in drawing attention to antisemitism in Quebec society. The Aberdeen School Strike is one of the earliest recorded student strikes in Canadian history, as well as one of the first organized protests against antisemitism in Canada.

Background

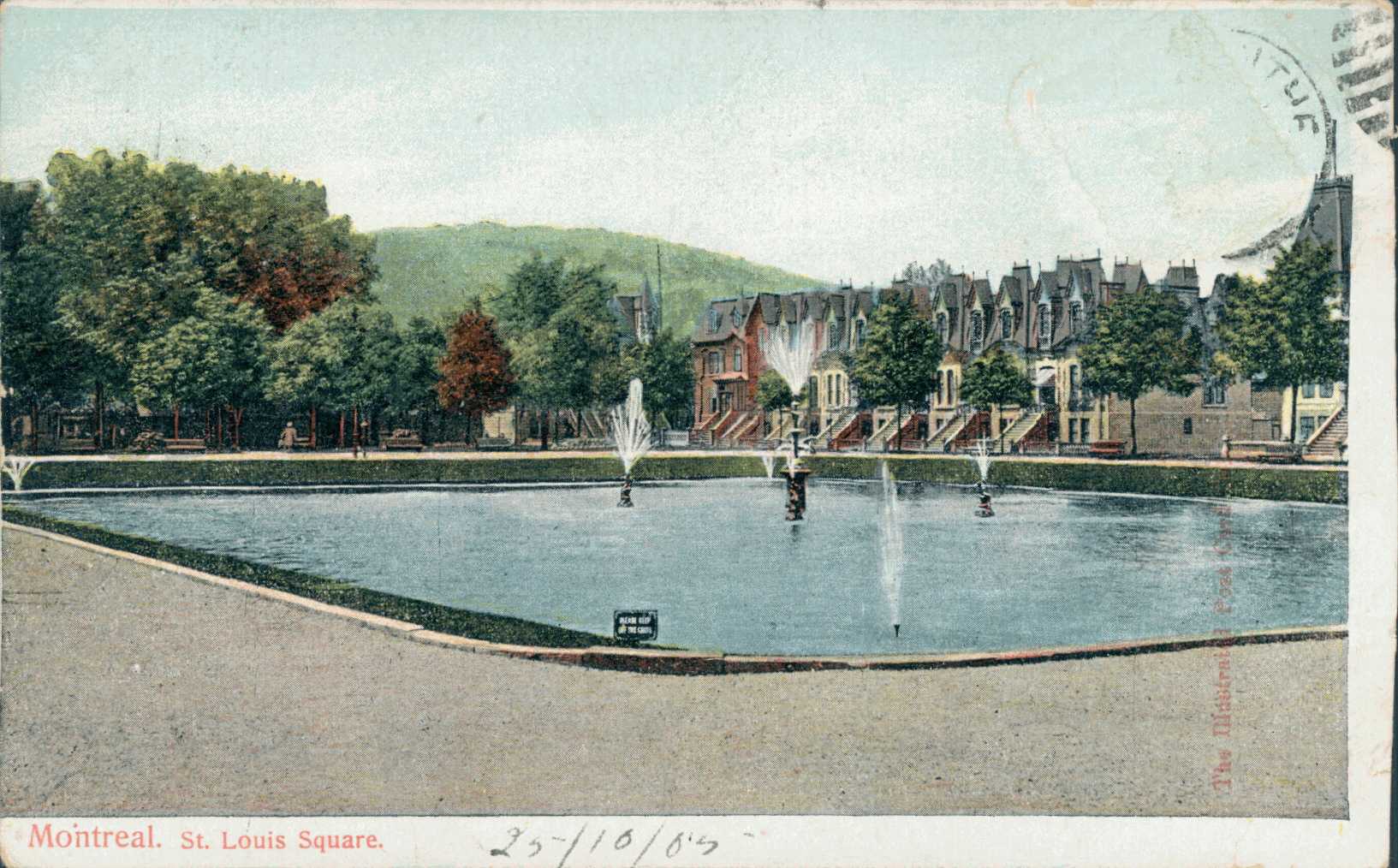

The Aberdeen School was located across the street from Square Saint-Louis, a prominent public park in Montreal. In 1913, the area around the park was also the centre of a local upper-middle-class French Canadian community. However, for the students at the Aberdeen School, the park acted as their playground.

The Aberdeen School’s student population was predominantly Jewish as well as Yiddish or Russian speaking. The teaching staff was mainly Protestant and anglophone. In 1913, the city’s English-speaking Protestant community was generally middle class or higher, while recent Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe were working class and often quite poor. The school belonged to the Protestant School Board of Montreal, which educated the Jewish community because they were excluded from the Catholic public school system (see Jewish School Question). Many of the students did not live near the school. They worked to support their families and lived in overcrowded, often dilapidated housing with limited access to clean water.

Students were aware of class issues, namely of the poor labour conditions their parents (and quite often they themselves) toiled in. There was indeed a class difference between them and the school staff. Students also knew that striking and picketing were effective tools to raise awareness of their grievances. Many members of Montreal’s Jewish community worked in the garment industry and had participated in the 1912 tailors’ strike.

Incident

An article from the Keneder Adler, a Yiddish-language newspaper based in Montreal, from 2 March 1913 shines light on the incident that led to the student strike. The article claimed that a teacher identified as “Miss McKinley” stated that: “when she first came to the school it had been very clean, but since the Jewish children arrived the school had become dirty... and that Jewish children should be shut out of Aberdeen school.”

The name McKinley was probably a pseudonym created by a newspaper to conceal the identity of the teacher involved. Moreover, at the time, the word “dirty” often referred to lice, something for which Jewish students were often singled out.

The remark was likely made on Thursday 27 February, as a photograph of the striking students was taken the next day.

Did you know?

In the early 20th century, antisemitism was prevalent in Quebec. In 1910, an antisemitic speech led to a wave of violence directed against Quebec City’s small Jewish community. The subsequent Plamondon libel case resulted in one of the first attempts to use the courts against hate speech in Canada.

Reacting to the teacher’s comments, five sixth-grade students ― Harry Singer, Frank Sherman, Joe Orenstein, Moses Skibelsky and Moses Margolis ― complained to the school’s principal, Henry Cockfield. Cockfield dismissed the teenagers as troublemakers.

Student Strike

On the afternoon of 27 February, the five students met to discuss their next move. They decided that they would go on strike the next day. Word travelled quickly amongst Aberdeen’s student body.

On the morning of 28 February, the students tried to enter their class but found that Miss McKinley had locked the door. The five students sent younger students to alert their fellow classmates of the strike. Several hundred students left the school and made their way across the street to Square Saint-Louis.

The children organized pickets and attracted considerable attention by the afternoon, including from the police who tried to disperse the crowd. Reporters from the city’s daily newspapers indicated that the students were well-behaved and disciplined. The pupils were likely well acquainted with appropriate protest behaviour, given the experiences of their parents in the tailors’ strike of 1912. A photo of the striking students was published by the Montreal Herald, with the headline “Wee Kiddies on Picket Duty at Aberdeen School Strike.”

Some of the striking students were dispatched to the head offices of a prominent Yiddish newspaper in the city, the Keneder Adler. Another delegation made its way to the Baron de Hirsch Institute to make their case to the leaders of the Jewish community.

Resolution

Members of the Baron de Hirsch Institute’s legislative committee met at the law office of Samuel W. Jacobs. At the time, Jacobs also represented the plaintiffs in the Plamondon libel case. They agreed that the matter of antisemitic remarks couldn’t be ignored. Jacobs and Herman Abramovitz, the rabbi of the Shaar Hashomayim congregation, would confront the school authorities.

When they did so, Principal Cockfield expressed his outrage at what he perceived as the students’ insolence. Meanwhile, Miss McKinley admitted that what she said was inappropriate; however, she excused herself by saying that her statements had been misinterpreted by the students. Jacobs and Rabbi Abramovitz presented the students’ demands to Cockfield. They demanded that Miss McKinley be transferred to another school and that the students be readmitted without punishment. Cockfield refused, saying the matter was for the school commissioners to decide. Jacobs and Rabbi Abramovitz indicated they would take the matter to the school commission, which was meeting the following week.

We do not know what came about from this meeting. However, the arrangement appeared to have satisfied the striking students. They returned to class the following Monday, despite Principal Cockfield’s threats of expulsion. He likely dropped his threat because any additional punishment would probably have been reported.

Legacy

Whoever Miss McKinley was, the available records do not show that any teacher was fired or transferred. However, an important consequence of the strike was the coverage it received in the news media. All of Montreal’s daily newspapers reported on the story, though the tone and degree of coverage differed by language and the community the papers served. Notably, an article from the Canadian Jewish Times on 7 March 1913 claimed that the strike was an important demonstration of the children’s “Jewish nationalism.” It argued that they were right to stand up for themselves.

Scholars reflecting on the strike in later decades noted it was an important turning point for Quebec’s Jewish community. The incident provided evidence of organized resistance to antisemitism. They further noted that it was a turning point for the city’s Protestant school board, which hired three Jewish teachers the following year.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom