On 1 September 1939, German forces invaded Poland, and the Second World War began. Donald Macdonald, then a boy in Winnipeg and later a federal Cabinet minister, remembered huddling around the radio in his grandparents’ living room, listening to the CBC reports of the Nazi invasion. “Even as a seven-year-old I understood that the world had just changed for the worse.”

The six-year-long war brought changes to the world order and forever altered Canada. The nation of then only 11 million people committed more than one million men and women to uniform. Among those most affected were young Canadians, whose voices were often lost in the cacophony of war. Children leave few written records, and their contributions are sometimes ignored by historians. But the war had a profound impact on their lives and families.

New Responsibilities

The adults started to disappear from children's lives soon after the war started. Older brothers, uncles and fathers enlisted in the military and were posted across the country or sent overseas. Male teachers slowly abandoned the classroom for service in the armed forces. They went from men in civilian dress to uniformed heroes — and sometimes martyrs. Occasionally, the wounded returned limping, cradling an arm, or missing limbs. Visible scars and invisible wounds to the mind left these veterans forever changed. Children and adolescents feared for their own loved ones.

While fathers and siblings were away on duty, children were expected to help around the house. New chores fell to children, everything from cooking to cleaning. Some mothers entered the paid workforce in white-or blue-collar jobs, and older children had to look after younger siblings. Newspapers carried ads seeking help for “general housework” or to “assist with children.” Girls, sometimes as young as 10 or 12, were soon employed in these positions. They were expected to do this as they balanced homework and other duties.

Schools were plastered with posters encouraging students to do their bit, to avoid careless talk that might aid the enemy, and to be on the lookout for spies. Teachers taught lessons about the war overseas and Canada’s contributions to beating the enemy. Occasionally, a student disappeared from school for a few days, and the teachers explained that the boy or girl needed a rest because they had lost a loved one in the war.All the while, morale was to be kept up. “There’ll Always Be an England” or “God Save the King” were sung with relish. No one wanted to be found wanting in their patriotism.

Helping the War Effort

Victory Gardens were encouraged. At school and at home, wherever there was a free patch of earth, children planted seeds and tended to their vegetables. Every bunch of carrots or canning of jam was portrayed as a blow in battling the Nazis. Children in rural areas sniffed at the city gardens as they engaged in back-breaking labour on farms.

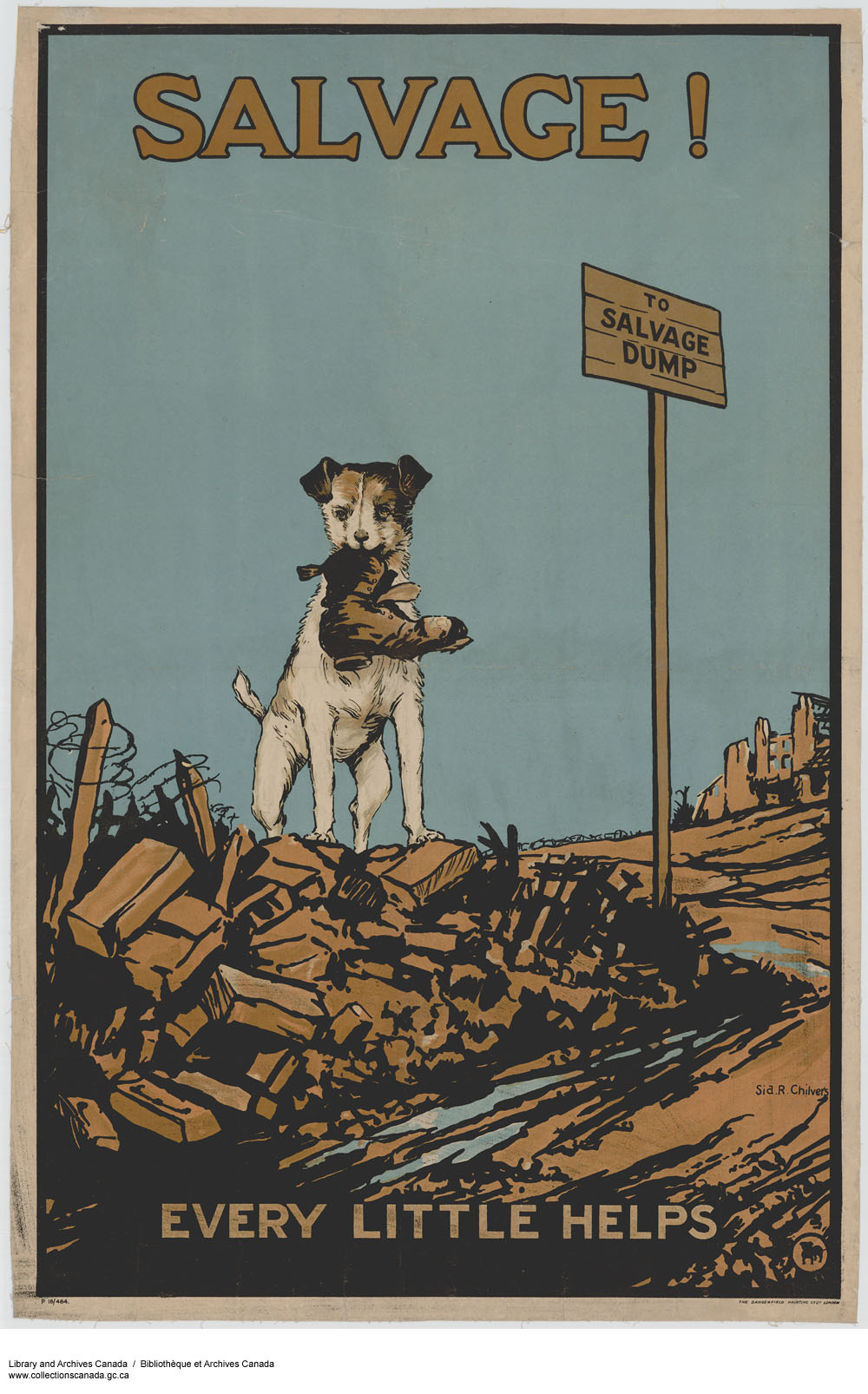

Recycling was also depicted as essential to the war effort. Paper and metal scraps were gathered in large salvage drives. Renderings of fats were collected from kitchens. Some children cried as the First World War artillery pieces from the battlefields of the Somme or Passchendaele, that had been situated in front of libraries or near city hall and climbed over in make-believe games, were now melted down to form new armaments. Canadians were instructed to recycle and reuse. Nothing was to be wasted in the fight.

Babysitting money and allowances went towards purchasing war stamps. The stamps were sold at school and in stores, and children purchased each for 25 cents. Sixteen filled up a $4 card, which was then sent to the federal government. In return, the child received a War Savings Certificate worth $5, to be cashed in after the war. The money raised was substantial; in the city of Edmonton in the single year of 1945, $41,926 was put towards War Savings Certificates.

The Girl Guides and Boy Scouts continued their good work, helping out those soldiers’ families that required aid and, in the case of the girls, knitting socks and scarves for military members overseas.Pen pals — soldiers, sailors, airmen and other children — were written to in Britain.

Closer to home, Canadian children went to school with more than 7,000 British children who had been evacuated from Britain to Canada, most of them in 1940, amid fears of a German invasion. These “guest children” stayed with Canadian families. Some made lifelong friendships with their Canadian foster parents and siblings; others were exploited and put to work for a pittance under harsh conditions and in unloving environments. Most of the children returned to their British families before the end of the war.

Germans, Italians and Japanese

Not all Canadian children were allowed to participate in the war effort. Canadians of German or Italian descent were teased, taunted or assaulted. The victims sometimes fought back, insisting they were as Canadian as anyone else, but most slunk away to the shadows, not anxious to draw attention to their heritage. Gloria Harris recounted that, "We were never, ever allowed to forget that we were foreign. I was born in this country, but I was ‘foreign.’”

Canadians of Japanese descent were actively harassed after Canada went to war with Japan in December 1941. Children were among the 23,000 Japanese Canadians who were viewed as threats to Canada's security and moved by the government from their homes on the British Columbia coast to communities and camps in the interior.Japanese Canadian writer Joy Kogawa kept the memory of the internment alive with her novel Obasan (1981).

Culture and Games

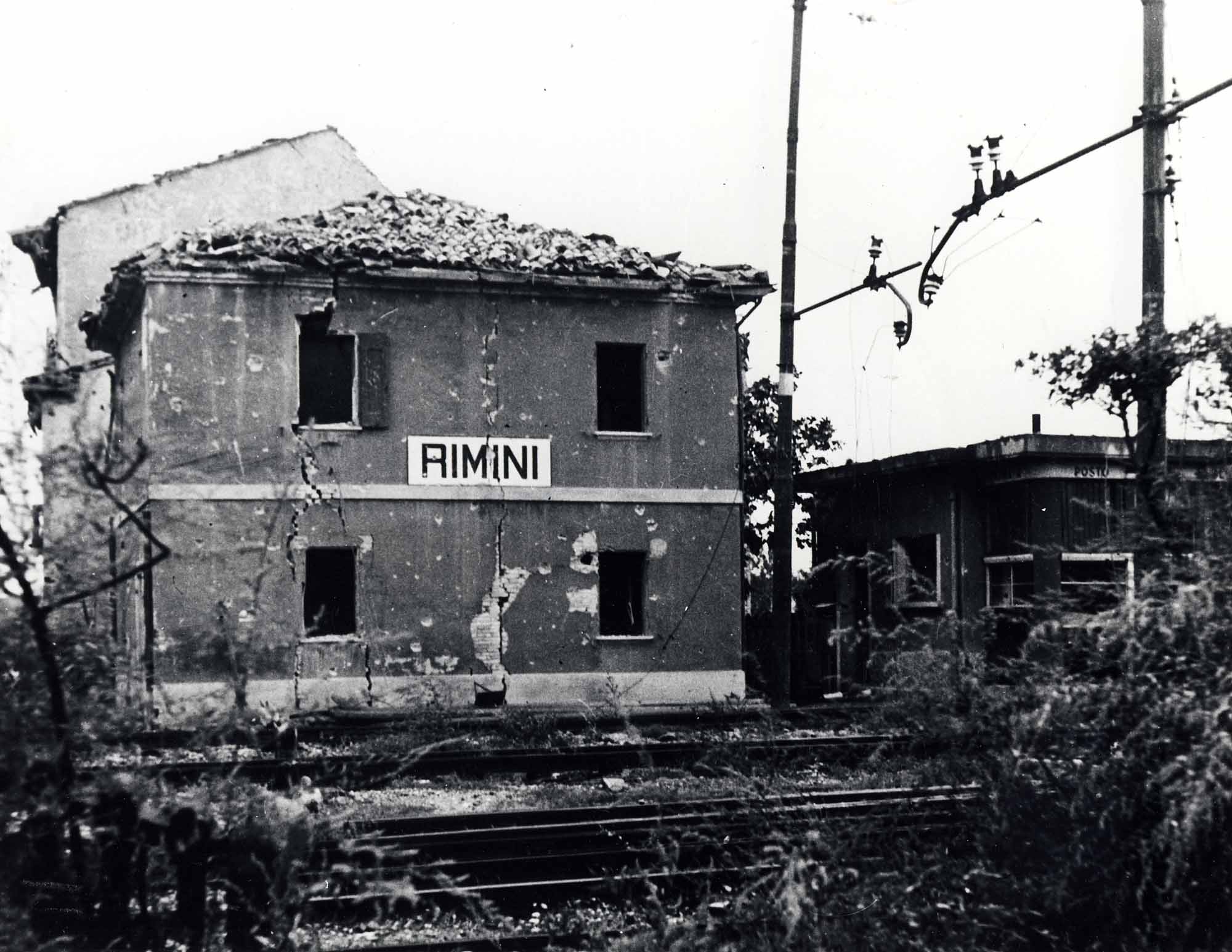

The war intruded into the lives of young Canadians. Blackout drills to prepare for enemy bomber attacks (which never came) left young minds wondering if Germany or Japan would soon launch an invasion. Sports teams adopted military names, such as Corvettes or Spitfires. Books for young adults were soon filled with stories of brave Canadians fighting the Germans. Children learned the names of famous battle sites such as Dieppe and Ortona, of the warships struggling to protect merchant vessels in the Battle of the Atlantic, and of Lancaster aircraft bombing German cities.

There was a surge during the war years of Canadian-content comics, known as “whites” because of the coloured covers and the black and white interiors. Canadian heroes Johnny Canuck, Nelvana of the Northern Lights, and Canada Jack battled Nazis and other villains.

There were wartime games too. A variation of the old favourite Snakes and Ladders was reissued as Bomb Berlin. New games included the bingo-like Bomb the Axis, as well as the bilingual War Game/Jeu de Guerre. Toy guns, helmets, and uniforms could be donned to defeat the enemy in make-believe battles.

One Canadian remembered of his youth, “When my uncle came home on leave once, I paraded around in his tunic, proudly pointing out the GS on his sleeve; there were no Zombies in our family!” The "Zombies" were those men who refused to serve overseas but were conscripted for home defence after the National Resources Mobilization Act of June 1940. The GS on the sleeve denoted General Service, while the Zombies, who refused to enlist for overseas service, were sneered at and said to have no soul. Of the many games played and the pride displayed, Québec author Roch Carrier recounted later in life, “Then we would die, moaning. And when we’d finished dying, we would start another war.”

Young Canadians went to the movies to see their cartoons and comedies, but many also watched war films like Mrs. Miniver— the story of the evacuation of British soldiers from Dunkirk, or wartime thrillers like Casablanca. Radio programs like L is for Lankey followed the stories of Bomber Command aircrews taking the fight to the Germans.

Shortages and Rationing

From the midpoint of the war, Canadian families dealt with shortages of sugar, meat, butter and gasoline. Rationing coupons were issued to provide a fair share to all. The conditions in Canada were far better than in war-torn Europe, but children lamented the lack of chocolate bars or Sunday drives to the country.

In the larger cities, especially Ottawa, Toronto, Vancouver, Montréal, and Halifax, there were housing shortages. Working-class families had to double up in homes or live in garages, basements or attics. Three kids to a bed was not uncommon. Other families took in female civilian workers or military personnel. These strangers in the home usually fit in nicely, although it could be odd for children to lose a brother to the services and gain an outsider in return.

In more rural communities, children witnessed the creation of new runways and flight schools for the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, which brought airmen from across the country and throughout the Commonwealth or the United States into their towns. The exotic New Zealanders, South Africans, and Australians walked city or village streets. The world was coming to Canadian communities across a nation festooned with 107 air training schools and 184 ancillary units at 231 sites.

Adolescents

While younger children were preoccupied with many projects, there was a fear that teenagers might be corrupted by the lack of supervision during the war. Drinking, dancing and cavorting with the opposite sex were moral corruptions for delinquent teenagers. Stories of youth gangs roaming the streets at night stealing tires and other rationed goods were more products of worry than reality, although some high-profile cases seemed to confirm fears that teenagers were on the brink of a downward spiral. Sensational films, like Where Are Your Children? featured parents who lost control of their wayward teenagers to the sins of pool halls, joy rides, and all manner of worrisome activities.

The non-conformity among teenagers was illustrated by the zoot suit craze. Following a trend in the United States, young people slipped into zoot suits — oversized pants cinched at the waist and worn high to create a balloon effect, topped off with a long coat with padded shoulders, a flamboyant bowtie, and a wide-brimmed hat. In several of the large cities, and especially Montréal, there were clashes between military members and zoot suiters. Pushing back against the authorities and the war effort, the anti-war and anti-conscriptionist zoot suiters were often attacked by Anglo gangs and service personnel, with large-scale clashes occurring in May and June 1944.

Losing Loved Ones

Children and teenagers treasured the black and white photographs of fathers or older siblings who were away fighting the war. Cameras were rare, and there might have been only a handful of images in the house. Meanwhile, the war overseas was always present. Children anxiously searched newsreels, which played before movies, for a glimpse of a familiar face. They fingered the souvenirs in their pockets that had been sent home from overseas by their brothers and dads and were invested with deep meaning. Letters were read over and over again, and young Canadians wrote to their loved ones about their activities at school or sports, the books they read, and how they hoped for a reunion.

Billie Housego, whose father was overseas for several years, yearned for when the war might end and when “my dad would be home to stay, there to sit down at the table with us morning and night, day in and day out.” These were the hopes of millions, although there was always much dread each time the telegraph boy rode down the street. Women, grandparents and children prayed he would not stop at their house or apartment with a message from the government, "We regret to inform you . . ."

The war in Europe ended on 8 May 1945, and children were among the millions of Canadians who were swept up in the excitement. Most young people took pride in having done their bit, with their service marked by knitting socks, helping in the home or on the farm, having dirty fingernails from gardening, and collecting mountains of scrap metal for recycling.

The celebrations, songs and outpourings of joy were mixed with the knowledge that some neighbours’ uncles, brothers and fathers were never returning home. Sometimes the loss struck even closer to home. That grief would stay with young Canadians all their lives, while others never forgot the relief in seeing a dad or brother walk through the family’s front door.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom