Canada wasn’t born out of revolution or a sweeping outburst of nationalism. Instead, it was created in a series of conferences and orderly negotiations, culminating in the terms of Confederation on 1 July 1867. The union of the British North American colonies of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and the Province of Canada (what is now Ontario and Québec) was the first step in a slow but steady nation-building exercise that would come to encompass other territories, and eventually fulfill the dream of a country A Mari usque ad Mare — from sea to sea.

But support for Confederation wasn’t universal. Indigenous people were never asked if they wanted to join, for example, and many others launched staunch opposition before and after 1867. From Indigenous to francophone resistance, opponents of Confederation have shaped the way we think about Canada as much as the Fathers of Confederation.

Reasons for Confederation

The union of British North America was a long-simmering idea. But by the 1860s, it had become a serious question in the Province of Canada. In the Atlantic colonies, however, a great deal of pressure would still be necessary to convert romantic ideas of a single northern nation into political reality.

Reasons for Confederation

American Annexation

The creation of a huge United States army during the American Civil War (1861–65), combined with Britain’s desire to reduce its financial and military obligations to its colonies in North America, boosted fears of American annexation. Canadian expansionism was considered by some as a pre-emptive action to reduce the chances that territories to the west and north of the Canadas would be annexed by the United States.

Trade

Confederation could offer the colonies strength through unity, an idea that gained steady support, especially in the wake of the US abrogation of the Reciprocity Treaty in 1866. In the face of dwindling external markets, Confederation could provide the colonies with the ability to sell goods to each other more easily.

Railways

Railways offered a new and infinitely faster way to transport goods and resources as well as troops and weaponry, which would help boost economies and strengthen borders. In 1862, the Province of Canada had refused to pay a portion of the costs for the Intercolonial Railway, proposed to run from Halifax to Québec. That sparked discussions among the Maritime colonies about merging into a single unit in the hopes of gaining political strength and attracting overseas financial investment. The Canadians would come around eventually.

Road to Confederation

The Great Coalition

In the early 1860s, the politics of the Province of Canada were marked by instability and deadlock, a result of the union of Upper and Lower Canada some 20 years earlier. The Great Coalition of 1864 united George Brown’s Reformers, John A. Macdonald’s Liberal Conservatives in Canada West, and George-Étienne Cartier ’s bleus in Canada East, in support of Confederation. It proved to be a turning point in Canadian history, paving the way for the Charlottetown Conference.

Charlottetown Conference

The Charlottetown Conference of September 1864 set Confederation in motion. The meeting brought together delegates from New Brunswick , Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island to discuss the union of their three provinces. However, they were persuaded by the Great Coalition from the Province of Canada — not originally on the guest list — to work for the union of all the British North American colonies.

Fathers of Confederation

The Charlottetown Conference was, in the words of Thomas D’Arcy McGee, an “extraordinary armistice in party warfare” — and one that paved the way for Confederation.

The 36 men traditionally regarded as the Fathers of Confederation were those who represented British North American colonies at one or more of the conferences that led to Confederation. The subject of who should be included among the Fathers of Confederation has been a matter of some debate. The definition can be expanded to include those who were instrumental in the creation of Manitoba (Louis Riel ), bringing British Columbia (Amor de Cosmos) and Newfoundland ( Joey Smallwood) into Confederation, and the creation of Nunavut ( Tagak Curley).

Mothers of Confederation

The wives and daughters of the original 36 men have also been described as the Mothers of Confederation for their role in the social gatherings that were a vital part of the Charlottetown, Québec and London Conferences. Official records of the 1864 Charlottetown and Québec Conferences are sparse. But historians have been able to flesh out the social and political dynamics at play in these conferences by consulting the letters and journals of the Mothers of Confederation. They not only provide a view into the experiences of privileged women of the era, but draw attention to the contributions those women made to the historic record and political landscape.

Québec Conference

Delegates gathered in Québec City to continue discussions started the previous month in Charlottetown. The broad decisions of Charlottetown were refined and focused into 72 resolutions, which became the basis of Confederation. Among the most important issues decided in Québec were the composition of Parliament and the distribution of powers between the federal and provincial governments.

Confederation, 1867

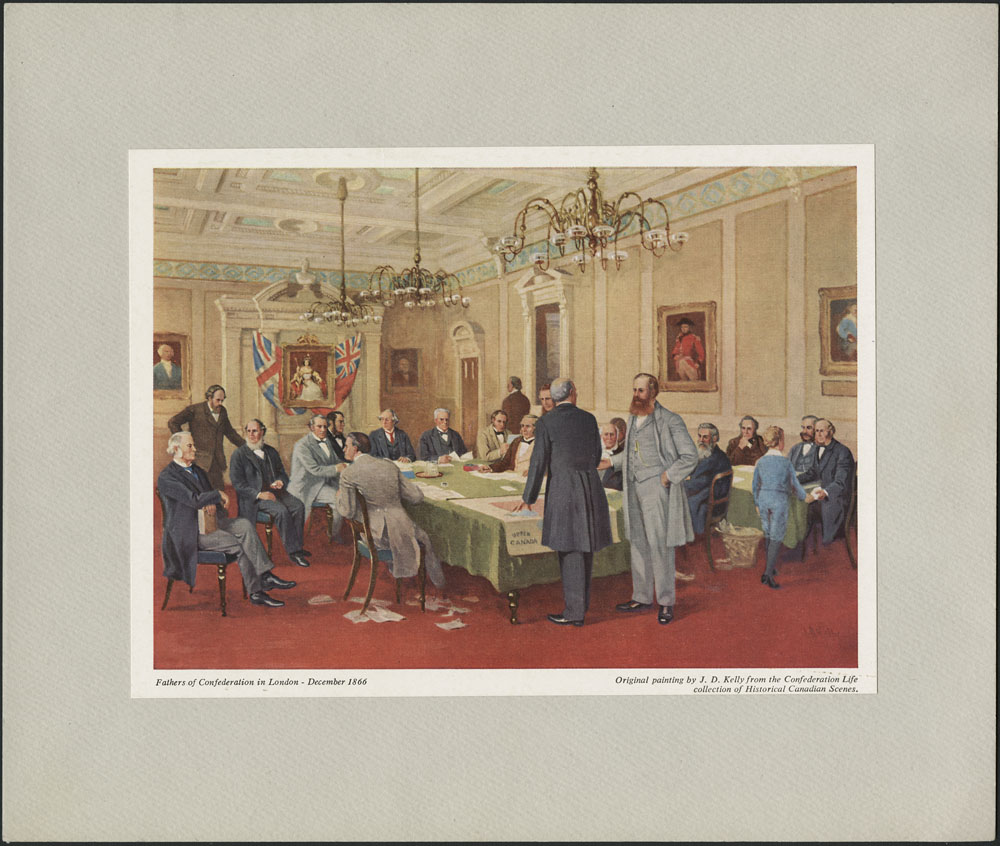

Worried about the cost of defending Britain’s North American colonies against potential US aggression, British Colonial Secretary Edward Cardwell was a strong supporter of Confederation. He instructed his governors in North America in the strongest language possible, to promote the idea, which they did. The London Conference, from December 1866 to February 1867, was the final stage of translating the 72 Resolutions of 1864 into legislation. The result was the British North America Act of 1867 (now called the Constitution Act, 1867), which passed through the British Parliament and was signed by Queen Victoria on 29 March 1867. It was proclaimed into law on 1 July 1867, which Canadians now celebrate as Canada Day .

Indigenous Perspectives

Indigenous peoples were not invited to or represented at the Charlottetown and Québec Conferences, even though they had established what they believed to be bilateral (nation-to-nation) relationships and commitments with the Crown through historic treaties. Paternalistic views about Indigenous peoples effectively left Canada’s first peoples out of the formal discussions about unifying the nation.

Despite their exclusion, Confederation had a significant impact on Indigenous communities. In 1867, the federal government assumed responsibility over Indigenous affairs from the colonies. With the purchase of Rupert’s Land in 1869, the Dominion of Canada extended its influence over the Indigenous peoples living in that region. Seeking to develop, settle and claim these lands, as well as those in the surrounding area, the Dominion signed a series of 11 treaties from 1871 to 1921 with various Indigenous peoples, promising them money, certain rights to the land and other concessions in exchange for their traditional territories. Most of these promises went unfulfilled or were misunderstood by the signatories. The years following Confederation saw increased government systems of assimilation, including reserves, the Indian Act and residential schools.

The Dominion Grows

British policy favoring the union of all of British North America continued under Cardwell’s successors. The Hudson’s Bay Company sold Rupert’s Land to Canada in 1870, and the young country expanded with the addition of Manitoba and the North-West Territory that same year. British Columbia was brought into Confederation in 1871 and PEI in 1873. Yukon was created in 1898 and the provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan in 1905.

Having rejected Confederation in 1869, Newfoundland and Labrador finally joined in 1949. In 1999, Nunavut, meaning “our land” in Inuktitut, was carved out of the Northwest Territories as part of the largest Indigenous land claim settlement in Canadian history.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom