Volumes have been dedicated to the Fathers of Confederation, but what about their wives and daughters, valuable record-keepers and political players in their own right? Official records of the 1864 Charlottetown and Quebec Conferences , which paved the road to Confederation, are sparse. But historians have been able to flesh out the social and political dynamics at play in these conferences by consulting the letters and journals of the Mothers of Confederation. They not only provide a view into the experiences of privileged women of the era, but draw attention to the contributions those women made to the historic record and political landscape. This article focuses on the efforts of six of these women.

Queen Victoria

Victoria, queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Empress of India (born 24 May 1819 at Kensington Palace, London; died 22 January 1901 at Osborne House, Isle of Wight).

It is fitting that Province of Canada delegates sailed to the 1864 Charlottetown Conference in Prince Edward Island aboard the Queen Victoria steamship. At the conference, Canadian delegates took the opportunity to propose British North American union to the Atlantic colonies. Victoria played a supportive role in the development of the Dominion of Canada, bringing together political figures from the British North American colonies through their shared loyalty to the Crown.

She was broadly known as the “Mother of Confederation,” who believed that Confederation would reduce defence costs and strengthen relations with the United States. “I take the deepest interest in it,” Victoria told a Nova Scotian delegation in London, “for I believe it will make [the provinces] great and prosperous.”

Victoria selected Ottawa as capital for the Dominion in 1867 as it was sheltered from potential American invasions and stood on the border between English and French Canada.

Victoria met with John A. Macdonald and four Canadian delegates in February 1867 as the British North America Act was passed before British Parliament. Macdonald recalled that Victoria said, “I am very glad to see you on this mission. […] It is a very important measure and you have all exhibited so much loyalty.”

Anne Brown

Anne Brown, née Nelson, wife, mother (born 1827 in Edinburgh, Scotland; died 6 May 1906 in Edinburgh).

The wife of Father of Confederation George Brown, Anne Nelson Brown is credited with influencing her husband’s worldview and bringing out his softer side. Historian Frank Underhill credits George’s willingness to partner with his political foes in the name of Confederation to Anne’s mellowing influence (see Great Coalition ). “Perhaps the real father of Confederation was Mrs. Brown,” he said.

Anne’s correspondence with George during the Charlottetown and Quebec Conferences provides a chronicle of the 1864 meetings for which there are no official records.

Brown’s letters outline conference progress, dinner menus, and the people and politicians he was meeting. He’d often write of the heated debates taking place, and reflect on his stance on representation by population.

He excitedly wrote to Anne on 27 October 1864 as the Quebec Conference concluded to tell her the constitution had been adopted:

"All right!!! Conference through at six o’clock this evening — constitution adopted — a most creditable document— a complete reform of all the abuses and injustices we have complained of! […] You will say that our constitution is dreadfully Tory— and so it is — but we have the power in our hands (if it passes) to change it as we like! Hurrah!"

Though many of Brown’s letters are preserved, few of Anne’s have survived; George could not stand the thought of others seeing his wife’s letters and would usually destroy them. Surviving letters from Anne are those George returned to her with comments in the margins.

Mercy Coles

Mercy Anne Coles, diarist (born 1 February 1838 in Charlottetown, PEI; died 11 February 1921 in Charlottetown, PEI).

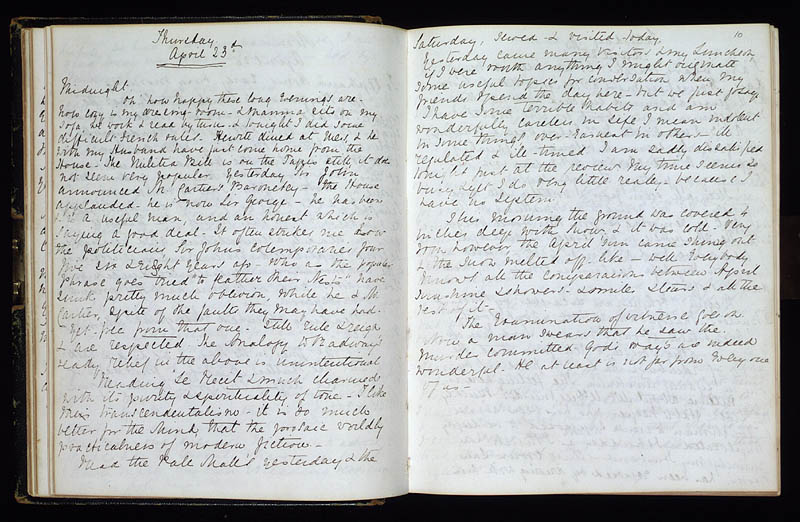

One of the daughters of George Coles, the first premier of Prince Edward Island, Mercy attended the Charlottetown and Quebec Conferences with her parents. Her diary, Reminiscences of Canada in 1864, is one of the most detailed sources about the events that preceded Confederation. The diary includes descriptions of the Fathers of Confederation and their personalities and brings light to the social politics of mid-19th-century Canada. Ballroom dances and socializing in the drawing room were not simply entertainments; for the delegates and their families, they were events at which valuable political networking took place.

As the daughter of Prince Edward Island delegate George Coles, Mercy was approached by senior political figures hoping that she would influence her father to support Confederation. George was not swayed easily by the proposed plan for Confederation, stating that he would only agree to the terms of union should leasehold tenure, a longstanding issue in PEI, be abolished in the colony (see PEI Land Question). The Province of Canada delegation would not bend to the request — leaving it off the 72 Resolutions presented at the close of the Quebec Conference — and George became a tough sell. (See also Prince Edward Island and Confederation.)

Mercy recorded her conversations at the Quebec Conference with future Prime Minister John A. Macdonald. “Mr. J.A. Macdonald dined with us last night,” she writes. “After dinner he entertained me with any amount of small talk.” Days after, Mercy continues: “I went to dinner in the evening. John A. sat along side of me. What an old Humbug he is. He brought me my dessert into the Drawing Room. The Conundrum.”

George Brown described Mercy Coles as one of George Coles’ “several attractive daughters, well educated, well informed, and sharp as needles.”

Mercy was aware of the political importance of the festivities and noted in her diary when social events did not achieve their intended purpose. She wrote on 14 October 1864:

"The Ball I believe was rather a failure as far as the delegates are concerned. The Quebec people never introduced the ladies nor gentlemen to any partners nor never seen whether they had any supper or not. The Col. Grays [John Hamilton Gray of PEI and John Hamilton Gray of NB] are both rather indignant at the way their daughters were treated."

Mercy Coles contracted diphtheria during her time in Quebec City and was treated by Dr. Charles Tupper, Premier of Nova Scotia. Her illness resulted in her absence from some of the festivities, but she received a continuous stream of visitors and reported the news they brought her.

Luce Cuvillier

Luce Cuvillier, businesswoman and philanthropist (born 12 June 1817 in Montreal, QC; died 28 March 1900 in Montreal).

The daughter of an important Montreal merchant, Luce Cuvillier has gone down in history as the “mistress” of George-Étienne Cartier, but the role that she played in Cartier’s life was far more than that of a mere corner in a romantic triangle. A cultivated woman and a great philanthropist, she has been described by historian Gérard Parizeau as Cartier’s muse, who guided and supported him throughout his political career.

According to historian Brian Young, Cartier and Luce Cuvillier lived together in the late 1860s (though they maintained separate addresses, for the sake of propriety), and their liaison was common knowledge in political circles. But none of his political adversaries ever used it against him, and journalists were content simply to report Miss Cuvillier’s presence at the social events that Cartier attended. In 1866, Luce was with him at the London Conference.

An independent businesswoman, Luce Cuvillier is fascinating because she was an unconventional figure in the Victorian Montreal of the mid-19th century. Cuvillier never married. Her contemporaries described her as an intelligent woman who took an interest in politics and never hesitated to express her opinions. She read the poems of Lord Byron and Charles Baudelaire and the novels of contemporary female author George Sand and, like her, smoked cigars and sometimes wore pants in her garden.

Lady Agnes Macdonald

Susan Agnes Macdonald (née Bernard), Baroness, writer (born 24 August 1836 in Spanish Town, Jamaica; died 5 September 1920 in Eastbourne, England).

Lady Agnes Macdonald was the second wife of Canada’s first prime minister, Sir John A. Macdonald. The couple married on the eve of Confederation (16 February 1867). As the first prime minister’s wife, Lady Macdonald set the standard for the 19th-century ideal of womanly behaviour — one that was devoutly religious, dedicated to family and committed to various good works in the community.

Lady Macdonald was also expected to support her husband’s political career by hosting social events and dinner parties for his colleagues, and adopting his “pursuits & occupations” (Lady Macdonald, 7 July 1867). Evidence suggests that she did not find social events easy or enjoyable, but was far more comfortable in the Ladies’ Gallery in the House of Commons. There she was known for transmitting messages to her husband using sign language for the deaf, or railing against his political opponents. Following a particularly heated debate during the 1878 session, Prime Minister Alexander Mackenzie observed a rather unseemly outburst when, “Lady Macdonald in the gallery, like the Queen of the day, stamped her foot and exclaimed ‘Did ever any person see such tactics!!’”

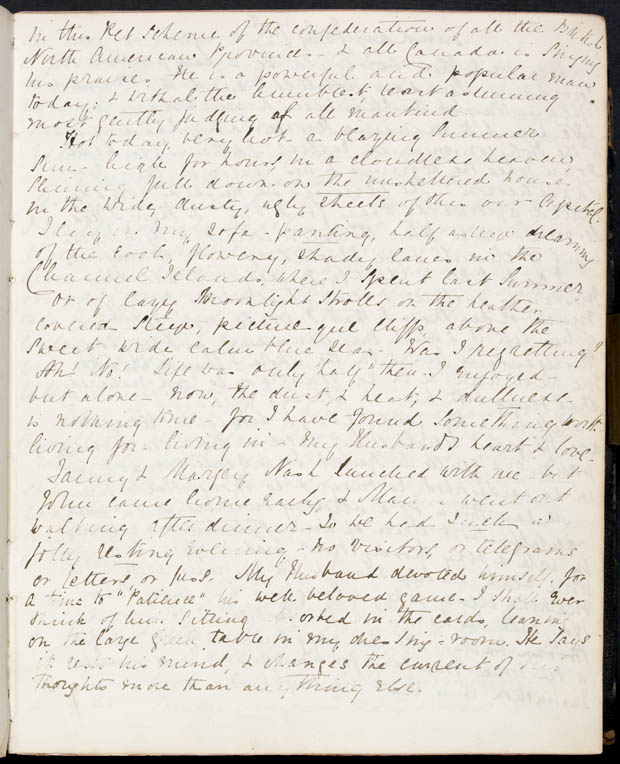

Lady Agnes could not vote or hold office, and therefore could not directly contribute to the political processes and policies that created the Dominion of Canada. But she was an informed and engaged observer of her world, and recorded her insights and experiences in her diary and her published travel and political sketches.

Lady Dufferin

Hariot Georgina Hamilton-Temple-Blackwood, Marchioness of Dufferin and Ava, viceregal consort and diplomat (born 5 February 1843 in Killyleagh, [Northern] Ireland; died 25 October 1936 in London, England).

Lady Dufferin transformed Rideau Hall into a social and cultural centre. She was the first governor general’s wife to tour Canada and became one of the most well-known and popular viceregal consorts (1872–78).

As governor general, Lord Dufferin was expected to be above party politics and refrain from attending debates in the House of Commons. His wife, however, was not bound by the same expectations and observed parliamentary proceedings in the House of Commons. Lady Dufferin provided her husband with detailed accounts, including the gestures and personalities of individual politicians, thus ensuring that her husband was kept informed of Canadian political developments. (She usually attended the House with an aide to the governor general, who also reported to the GG about House matters.)

Lady Dufferin also described parliamentary affairs in letters to her mother (published in 1891 as herCanadian Journal). Her accounts included commonplace observations — “The business was not very interesting, but I was rather amused, as a number of people made very short speeches, and one saw their ‘tricks and their manners’” — as well as descriptions of historic moments.

“[8 April 1873] I went to the House, as a scrimmage was expected. […] The Opposition had asked [on 2 April] for a Committee to inquire into the conduct of members of the Government, accusing them of bribery. They lost, and then the Government itself asked for the same Committee, saying they courted inquiry. There was a good deal of irritation about the whole affair.”

Lady Dufferin was referring to the Pacific Scandal that led to the 1873 prorogation of Parliament and the fall of the Macdonald government.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom