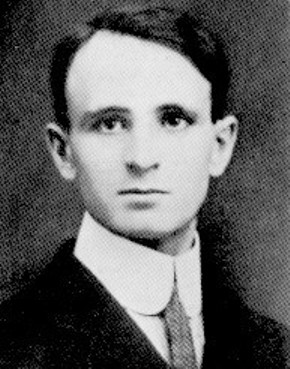

Edmond de Nevers (born Abraham-Edmond Boisvert), French-Canadian essayist and translator (born 12 February 1862 in Baie-du-Febvre, Yamaska County, Lower Canada; died 15 April 1906 in Central Falls, Rhode Island, United States of America). He is known for his publications L'Avenir du peuple canadien-français (1896) and L'Âme américaine (1900).

Early life

Edmond Boisvert grew up in a farming family (see Agriculture in Canada). He changed his name to Edmond de Nevers around 1888, convinced that his family was one of the oldest and best of the French nobility.

The man who would later become de Nevers entered the Latin Elements class at the Nicolet seminary in 1873. He immediately distinguished himself by his exceptional memory, his gift for languages, his talents as a prose writer and poet, and his originality. It was during his time at the seminary that he experienced the first stirrings of doubt that would gradually lead him to unbelief.

In 1880, he was accepted as a clerk in a Trois-Rivières law office. After being called to the Bar in 1883, he practiced law for some time, but became bored with the profession.

Departure for Europe

Dreaming of discovering the old countries, Edmond de Nevers boarded a transatlantic liner in 1888.

Berlin was his primary destination. He wanted to improve his German, draw on the knowledge of German universities and perfect his violin skills. He was an eternal jack-of-all-trades who spent his days and nights studying music, medicine, ethnography, history and literature.

After two years in Germany, de Nevers visited Austria, Switzerland, Hungary, Italy, Spain, Portugal and possibly Algeria. He settled in Paris in 1891, where he remained until 1900, apart from a stay in America (notably New England, where his family had moved) from 1896 to 1998. Since he was a polyglot, he landed a job as an editor at the Havas agency, translating international news.

In 1893, he published his first work, a translation of two plays by Henrik Ibsen, in collaboration with Pierre Bertrand. As soon as this work appeared, he began work on a second, this time entirely focused on the French-Canadian people, about whom he had been thinking and dreaming ever since he left Canada. In 1895, he confided to his friend Dr. J.-M. Brisebois: "I think, I write, I dream: I think about the country, about its future, I form patriotic projects." De Nevers recorded his thoughts in L'Avenir du peuple canadien-français, which was published in the spring of 1896.

De Nevers only had one ambition, one message to deliver in his essay: as the French-Canadian nation is threatened with being swallowed up by "the rising tide of Anglo-Saxonism", we must urgently work towards national recovery by instilling a strong dose of patriotic pride into the "soul" of the French-Canadian people. He repeated these words on every podium, sometimes taking advantage of the most seemingly distant and abstract subjects to reiterate his nationalist views. (See also French Canadian Nationalism.)

Return to Canada

In 1900, Edmond de Nevers returned to America, having completed another two-volume essay, this time devoted to the United States. The writing of L'Âme américaine (1900) had cost him his last strength. When he returned home, he was a man broken by overwork and paralyzed by the ravages of syphilis, from which he had been suffering for more than ten years.

Thanks to the support of Adélard Turgeon, whom he had met in Paris, he settled in Quebec City and became a publicist with the provincial government’s Department of Lands, Mines and Fisheries, replacing Arthur Buies, who had just died. It was not the career of which he had dreamed.

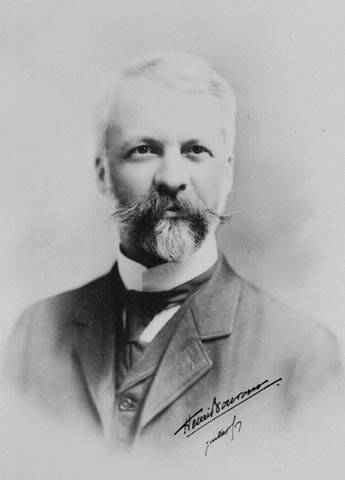

Nevertheless, his ideas were well known, and his work began to gain influence in the small nationalist circle that was taking hold in French Canada. (See also French Canadian Nationalism.) Olivar Asselin regularly visited his apartment, as did Henri Bourassa, Rodolphe Lemieux and Abbé Camille Roy. De Nevers was praised for his denunciation of Anglo-Saxonism and its anti-Semitic attacks, as this thinking was fuelled by a profound racialist (the world is divided into several races) and racist (certain races, including the Jewish race, are inferior to others) ideology (see also Antisemitism in Canada.)

End of Life

Edmond de Nevers dreamt of leading a national revival movement. But his body could not keep up. He left behind, among other things, a book of poetry, an account of his travels, a work on political economy and a novel of manners, all manuscripts that have now been lost.

In 1903, he moved to his parents' home in Central Falls, Rhode Island. During the last three years of his life, his illness tortured him increasingly, causing him to become delirious.

He died on 15 April 1906.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom