The First Special Service Force was a unique American-Canadian commando-type unit formed during the Second World War. Although it only existed from July 1942 to December 1944, it participated in operations in the Aleutian Islands, Italy and France and earned a fearsome reputation among German troops. Many of today’s American and Canadian special forces units base their heritage on the First Special Service Force.

Background

The First Special Service Force (FSSF) had its origins in Lord Louis Mountbatten’s Combined Operations Command. The concept was a small, elite force that could operate behind German lines to attack high-profile targets such as Norwegian hydroelectric plants. Because neither British nor Norwegian troops could be spared, the unit would be composed of American and Canadian soldiers.

In June 1942, U.S. Army Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Frederick received orders to organize and command this new unit. He and his staff immediately began recruiting men with experience working outdoors. The new unit assembled at Fort William Henry Harrison in Montana, which offered the rugged terrain and weather conditions necessary for mountain, winter and airborne training.

Organization

The 2,300-man FSSF was organized into three 600-man regiments, each of two battalions. All battalions had three 100-man companies of three platoons. A separate service battalion, manned only by Americans, supported the three regiments. It provided all administrative, medical and maintenance support for the force, allowing the combat element to focus on training and, later, on fighting.

The name for the Canadian component of the FSSF was the 1st Canadian Special Service Battalion. In practice, however, Americans and Canadians were dispersed between all three regiments, where the 650 Canadian soldiers and 47 officers made up one-third of the fighting element and about half of the leadership positions. As of August 1942, the senior Canadian was Lieutenant-Colonel Don Williamson, the unit’s second-in-command. Soldiers of the unit referred to themselves as “Forcemen.”

Weapons

FSSF small arms were mostly the same ones issued to other US army combat units. The force used the Johnson Light Machine Gun, which was also used by the US Marines. Forcemen liked its relatively light weight (about the same as a loaded M1 Garand rifle) and rate of fire of up to 600 rounds per minute. Many Forcemen believed the “Johnny Gun” was “pound for pound, the most valuable weapon” they possessed.

As a commando-type unit, Forcemen were trained in hand-to-hand combat, for which a fighting knife was essential. Frederick and some of his officers contributed to the design of the Fighting Commando Knife, Type V-42, which was based on the British Fairbairn-Sykes Fighting Knife. The V-42 had a double-edged, carbon-steel blade capable of penetrating a German helmet.

Dress and Insignia

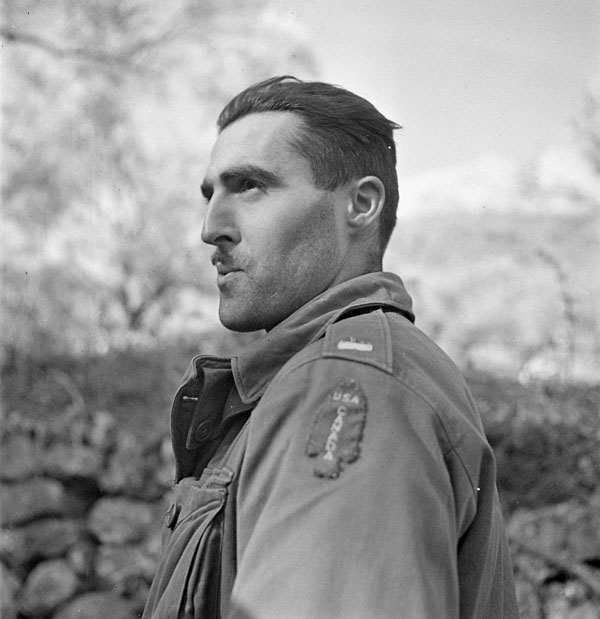

In addition to American weapons, the FSSF also used American combat and dress uniforms. A unique arrowhead-shaped red shoulder patch with “USA” stitched horizontally in white and “CANADA” stitched vertically was worn on the upper left sleeve of uniforms. On dress uniforms, Forcemen wore crossed arrows on their lapels, with a metal disc bearing either “U.S.” or “Canada” above them, and a red, white and blue braided shoulder cord or lanyard on the left shoulder. A cloth oval in horizontal stripes of blue, white and red was used behind American jump wings.

Aleutians

In the fall of 1942, now-Colonel Frederick was told the FSSF would participate in an invasion of Kiska in Alaska’s Aleutian Islands, which had been occupied by the Japanese since early June 1942. In April 1943, the force completed amphibious training in Virginia in preparation for the operation; it departed San Francisco in July.

The FSSF and arrived in the Aleutians two weeks later, part of a 34,000-man joint American-Canadian assault force supported by ships and aircraft. The landing on Kiska was anticlimactic, however, because the Japanese had secretly evacuated the fog-shrouded island before the invasion.

Italy

The FSSF was next selected to join the Italian Campaign. The unit sailed on 27 October aboard the Canadian Pacific troopship Empress of Scotland (formerly Empress of Japan). It landed at Naples on 19 November and entered the line alongside American troops.

The force’s first mission was to capture several mountaintop outposts that were part of the German Bernhardt or Winter Line, held by the elite 15th Panzergrenadier Division. Previous American, British and Canadian attacks had failed.

The FSSF assaulted German positions on two high peaks, Monte la Difensa in front and Monte la Remetanea behind. Both were more than 900 metres high. Frederick assigned the mission to his 2nd Regiment.

The first night saw a gruelling seven-hour climb up the sheer face of Monte la Difensa, with all supplies — including water — carried by the soldiers, followed by a lay-up during daylight. On the second night, the assault force scaled the few remaining metres to the top; they attacked at dawn on 3 December. The attackers took the Germans completely by surprise in a final rush.

For the next two days, the 2nd Regiment held Monte la Difensa, repelling a German counterattack on the morning of 4 December. The next day, the regiment’s 1st Battalion pushed forward along the narrow ridge that led to Monte la Remetanea, about 900 metres to the north. The battalion came under machine-gun and mortar fire but pressed on and took its objective.

By 8 December, the entire hill mass was in Allied hands. The FSSF had fought with distinction and achieved its objectives in its first action, but at a cost of more than 525 casualties. After a short rest, the force seized three more German-held heights that blocked the way to Monte Cassino. Another rest followed for the unit, its combat element now reduced by 1,400 dead or wounded.

Anzio

Meanwhile, American and British troops had conducted an amphibious landing at Anzio, only 50 kilometres south of Rome and about 115 kilometres behind German front lines. Their objective was to open the way to the Italian capital. Initial caution by the American commander led to a defensive perimeter instead of an advance inland, which gave the Germans time to seal off the bridgehead and created a four-month stalemate.

The Allies reinforced their bridgehead with additional troops, including the FSSF under newly promoted Brigadier-General Frederick. The force landed on 2 February, more than a third understrength, and dug in for about 13 kilometres along a canal.

Not content with defensive actions, the force embarked on a series of nighttime actions to kill or capture as many Germans as possible. One patrol returned with a German diary that noted “The ‘Black Devils’ are all around us at night. They are upon us before we even hear them coming.” The nickname stuck.

Frederick added to these fears when he printed calling cards in German to leave on the bodies of dead enemy soldiers. It displayed the unit’s insignia with words that translated as “The worst is yet to come!”

Once the Americans replaced their commander with a more aggressive leader, the Allies finally broke out in conjunction with the capture of Monte Cassino. During their time on the line, the FSSF were in action for 99 continuous days.

Rome

Lieutenant-General Mark Clark, commander of Fifth Army, was so impressed with the FSSF’s performance that he allowed it to spearhead the Allied entry into Rome. The force battled its way toward Rome and entered the city early on 4 June. They fought through the city and captured six bridges across the Tiber River by 11:00 p.m.

On 23 June, Frederick announced his departure from the FSSF and promotion to major-general. Hardened Forcemen “cried like babies” at the news. Colonel Edwin Walker replaced Frederick.

Southern France

Operation Dragoon entailed a massive amphibious assault along a 60-kilometre stretch of French coast between Toulon and Cannes by American and French troops. The FSSF’s part in the operation was to seize two small German-held islands about eight kilometres off Toulon. At 1:30 a.m. on 15 August, the Forcemen disembarked from their transport ships and paddled ashore in inflatable rafts.

Landing in silence on the two islands, the Forcemen advanced against strong enemy resistance. On Île du Levant, the 2nd Regiment quickly moved across the island and forced 200 Germans to surrender. On nearby Port-Cros, it took the 1st Regiment two days to subdue its stubborn defenders with the help of naval gunfire. The force then landed on the Riviera, where it remained until 30 November.

Disbandment

On 5 December, the FSSF paraded in a small village near Nice, where its disbandment was announced. During its short existence, the force inflicted an estimated 12,000 casualties on the enemy and captured 7,000 prisoners.

Battle Honours

The FSSF received several American campaign streamers and nine Canadian battle honours, all of which were authorized to be borne on unit colours. These honours are:

Monte Camino

Monte La Difensa—Monte La Remetanea

Monte Majo

Anzio

Rome

Advance to the Tiber

Italy, 1943‒1944

Southern France

North-West Europe, 1944

Did you know?

Because the FSSF was disbanded at the end of the war, its battle honours were not perpetuated by any unit until the creation of the Canadian Airborne Regiment (CAR) in 1968. When the CAR was disbanded in 1995, these honours once again went into limbo. In 2006, the Canadian Special Operations Regiment was established, and in 2008 it was authorized to perpetuate the honours of the FSSF.

Legacy

In September 1999, the main highway connecting Helena, Montana, to Lethbridge, Alberta, was renamed the “First Special Service Force Memorial Highway.” This highway was the main route taken by Canadian soldiers to join their American comrades for training at Fort William Henry Harrison.

On 3 February 2015, the US government awarded the Congressional Gold Medal to the FSSF in recognition of their achievements during the Second World War. It is the highest civilian honour awarded by Congress.

Devil’s Brigade

The FSSF was the subject of an American film, The Devil’s Brigade (1968), based on a book of the same title by Robert H. Adleman and George Walton. The film dramatizes the training process and the mission to take Monte la Difensa during the Italian Campaign. Considered a classic war film by many, it has been criticized for historical inaccuracies—including cultural stereotypes and an invented storyline about animosity between Canadians and Americans during the FSSF training process.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom