Fort Mackinac, located on Mackinac Island, is the third fort to guard the Straits of Mackinac. It was a strategic centre in the Upper Great Lakes from 1780 to 1895. The British constructed the fort from 1780 to 1781 during the American Revolution. Fort Mackinac’s position on the island’s bluffs was designed to offer a strong defensive position as well as defend the village of Mackinac and anchorage of Haldimand Bay. It was transferred to American control in 1796, captured by the British during the War of 1812, and returned to the US in 1814. It remained a military post until 1895.

Construction of Fort Mackinac

With the outbreak of violence in 1775 between Great Britain and the 13 colonies (see American Revolution and Canada), the Straits of Mackinac regained its strategic importance for the fur trade and to retain alliances with Indigenous nations. Fort Michilimackinac, initially constructed by the French in 1715, served as the British centre for military, diplomacy, and trade. Like the French, the British used the post as a place to encourage Indigenous peoples to fight alongside them or remain neutral. However, American military success at the southern end of Lake Michigan made the British acutely aware of the post’s multiple vulnerabilities. The stockade was overlooked by sand dunes and threatened with collapse during storms, while the waterside pickets were being undermined by waves. Additionally, the fort’s anchorage was subject to the formation of sand bars and exposed to the weather.

Patrick Sinclair, the newly arrived Lieutenant-Governor and Superintendent of Fort Michilimackinac, decided to place the British establishment in a more defensible position. Shortly after his arrival, he made a survey of Mackinac Island along with a mason, carpenter, brick maker, and farmer. After finding a suitable harbour, which was defensible from the bluffs above and quickly named Haldimand Bay, Sinclair sent a report that included a sketch of the proposed fort to Governor Haldimand. Instead of waiting for a reply and formal approval, Sinclair began the process of relocating the fort, its garrison, and village.

Before occupying the island, Sinclair needed Anishinaabe permission. The site of the proposed wharf and village on Haldimand Bay was a gathering place for the Anishinaabe. Additionally, Mackinac Island and its bluffs held spiritual meaning for the Anishinaabe. Sinclair therefore instructed Charles Gautier, a Métis resident and trader, to obtain permission from the Anishinaabe to utilize the island. Permission was granted to cut down some bush, and Sinclair ordered his men to begin clearing a site on the island during the fall and winter of 1779 and 1780.

When permission to relocate Fort Michilimackinac arrived in May 1780, Sinclair began construction of Fort Mackinac. Sinclair designed the general layout of the fort and appointed Captain Samuel Richardson to oversee construction. Troops, Indian department employees, and traders were employed in the fort’s construction. During the winter of 1780-81 the barracks and the Catholic Church of Ste. Anne at Fort Michilimackinac were dismantled, hauled across the ice, and reassembled in the fort and village respectively.

In the spring of 1781, the lieutenant-governor negotiated a deal with the Anishinaabe (Chippewa/Ojibwe) to secure British ownership of Mackinac Island. For £5,000 worth of goods, the Anishinaabe confirmed British use and ownership of the island. The British garrison formally moved to Fort Mackinac in the summer of 1781 after burning the remaining structures in and around the old fort’s grounds.

Governor Haldimand was concerned by the high construction costs and associated expenses and ordered three officers to investigate the receipts in 1782. While the investigation was underway, Sinclair resigned his post in September 1782 and returned to Quebec to defend himself. Regardless, work on the fortifications and buildings continued until 1783.

Occupation by United States

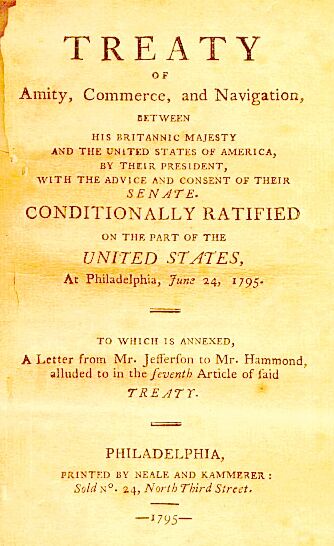

The 1783 Treaty of Paris formerly ceded control of Mackinac Island and Fort Mackinac to the United States. The British, however, retained the fort until an American company under Major Henry Burbeck assumed control in 1796. After leaving Fort Mackinac, the British military moved about 65 kilometres away to St. Joseph’s Island and built Fort St. Joseph, which overlooked the Straits of Mackinac.

Upon occupation of the fort on Mackinac Island, American troops found that neither the buildings nor the walls had been maintained and that several buildings, including the officers’ barracks, were left partially constructed. From 1796 to 1812 the U.S. military completed construction of the officers’ barracks, re-erected palisades, as well as repaired and built new stone walls at Fort Mackinac.

British Control During War of 1812

Fort Mackinac was the site of the first British victory in the War of 1812. (See Battle of Mackinac Island.) The British garrison at Fort St. Joseph received news of the declaration of war and began preparation to capture Fort Mackinac. Unaware of the declaration, American officer Lieutenant Porter Hanks was unaware of the declaration but heard rumours of unusual activity at the British fort and sent trader Michael Dousman to investigate. Dousman was captured by the British and released to warn the villagers at Mackinac. Soon after, British Captain Charles Roberts and his troops landed on the north side of the island and placed a canon on a ridge above the fort. After firing a single shot, he demanded and received Hanks’ surrender.

After a series of victories in the Lower Lakes, the US attempted to recapture Fort Mackinac in the summer of 1814. Arriving in Haldimand Bay, the US flotilla attempted to shell the fort but most of the shots failed to reach the walls. Lieutenant-Colonel George Croghan then attempted to repeat the success of the British landing on the north shore in 1812. Lieutenant Colonel Robert McDouall successfully repelled the attack, killing 13 Americans, including three officers. Another seven died of their wounds. McDouall’s success at the Battle of Mackinac Island meant the fort and Upper Lakes remained under British control until the end of the war.

American Post 1814 to 1895

The 1814 Treaty of Ghent, which ended the War of 1812, returned Fort Mackinac and the Straits to American control. The decline of the fur trade and the movement of the frontier westward led to Fort Mackinac’s declining importance. With the 1822 construction of Fort Brady in Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, Fort Mackinac lost its status as a key border post with British-Canada. Fort Mackinac and its garrison became a strategic reserve. Soldiers from Fort Mackinac were deployed in military operations from 1837 to 1840 during the Seminole War, in 1848 during the Mexican American War, and from 1857 to 58 during the Santee Indian Uprising. Fort Mackinac generally remained un-garrisoned during the Civil War. It was briefly re-occupied from April to September 1862 by a company of Michigan volunteers who were guarding three prominent Confederate sympathizers from Tennessee. The fort was permanently re-garrisoned from 1867 until its transfer to Michigan in 1895.

Tourism and Legacy

By 1870, tourism had become the mainstay of the Mackinac Island economy. In 1875, the U.S. federal government created the Mackinac National Park to preserve the island’s unique features and history. From 1875 to 1895, in addition to their military duties, the soldiers of Fort Mackinac acted as park wardens. Fort Mackinac and the Mackinac National Park were then transferred to the state of Michigan in order to reduce federal expenses. In September 1895, the last U.S. military troops left the Fort.

Fort Mackinac is one of a few surviving pre-revolutionary forts in the United States – the ramparts, sally ports, and blockhouses all date to this period. The oldest building in the fort is the stone officers’ quarters, which was begun by the British and finished by the Americans. Other reconstructed or original buildings are from the 1820s to 1880s. These include the commissary, post headquarters, quartermaster’s store, bathhouse, barracks, schoolhouse, hill quarters, hospital, wood quarters, and guardhouse.

Fort Mackinac, as a State Historic Park, now serves as a living history museum. Within its walls a variety of artifacts, displays, and re-enactors highlight the military, social, familial, cultural, and political history of the Fort, the island, and the Straits of Mackinac. Since becoming Michigan’s first State Park in 1895, Fort Mackinac and Mackinac Island have drawn thousands of tourists annually.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom