History

Voyageurs, Traders and Settlers

The first French speakers to come to Manitoba were explorers working for the Hudson’s Bay Company. In the 1660s Pierre-Esprit Radisson explored into the territory of Northern Manitoba from Hudson’s Bay, although it was not until the 1730s that explorer Pierre de La Vérendrye and his sons established a more permanent presence in the south of the future province. The fur trade encompassed the majority of the early European presence in Manitoba, both before and after the Conquest of New France. Retired voyageurs formed the earliest settlers, establishing farms on the banks of the Red and Assiniboine rivers. Many such individuals married à la façon du pays, taking Indigenous wives. Their children, existing in both worlds, came to see themselves as a different people. This newly developing Métis identity (among whom there were both francophones and anglophones) would grow in succeeding years and prove to be a major and enduring force in Manitoba politics.

The Church

The Catholic presence in the Francophone community was initially limited, but by the early 19th century the Church hierarchy in Québec was persuaded of the need to ensure its presence in the burgeoning Red River Colony. In 1818, Joseph-Norbert Provencher, a young priest, arrived in Manitoba and began a 30 year mission which provided a steady hand to guide the francophone and Catholic population of Manitoba (see Missions and Missionaries). Provencher was succeeded as Bishop of St. Boniface by Alexandre Taché who consolidated the Church’s work and ensured a degree of political leadership among francophones. Among Taché’s moves was selecting bright pupils to send for further study in Québec. One such student would go on to be the founder of Manitoba: Louis Riel.

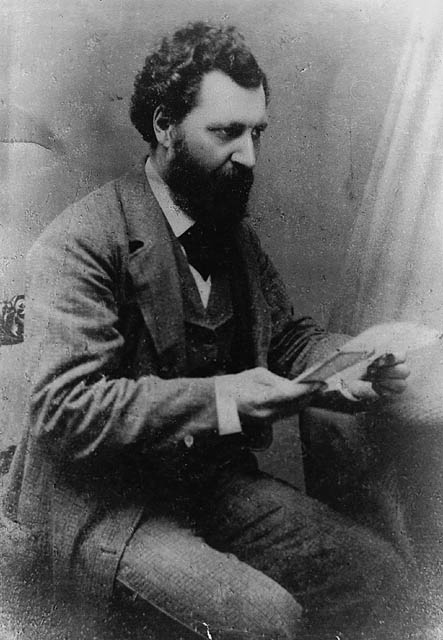

Louis Riel

Sent to study at a minor seminary (the Collège de Montréal) in 1858, Louis Riel came back ten years later to find a community facing significant changes and deeply anxious about the possibility of annexation to Canada. A refusal to allow surveyors from Canada in 1869 led to the Red River Rebellion, during which Riel formed a provisional government which took control of the Colony. The provisional government put forward a list of terms for Manitoba’s entry into Confederation, most notably including land provisions for the Métis as well as linguistic and confessional equality between English Protestants and French Catholics. The dominion eventually consented to the terms and put forward the Manitoba Act as an act of Parliament. In 1870, Manitoba joined Confederation as a bilingual province, at least as far as education, law, and the legislature were concerned.

Changing Demographics

Remote and difficult to access as it was, population growth in the Red River Colony during much of the 19th century was primarily natural, rather than the result of significant immigration. This maintained the demographic balance in favour of French speakers, both Canadiens and Métis, who formed a slight majority in 1870. Thus, when Riel’s government pushed for linguistic equality, this was a reflection of the demographics of the colony.

The demographic balance of 1870 did not last. Immigration from Ontario increased as the railway made its way into Manitoba. Occasional settlement of francophones from Québec, New England, and Europe only made up a small part of this migration. By 1890, francophones represented 10 per cent of the population. The political leadership of the province was not ignorant of this fact and set out to systematically remove the protections granted to the French language.

A major blow came that year with the passing of the Official Language Act, which made English the only official language of the legislature and the courts. Taking stock of demographic reality, the political and religious leaders of the francophone community opted to put their efforts towards preserving confessional schools (see Separate School). These, too, were soon targeted. The resulting Manitoba Schools Question not only had a profound impact on the federal politics of the time, but also set the mold for French language rights in Manitoba for the following 80 years. Parliament, ostensibly the defender of minority language rights, was unprepared to battle the provincial government on this issue. Manitoba’s anglophone majority had turned demographics into political reality.

The final blow came in 1916. A series of reports in the Manitoba Free Press on the poor state of rural education in Manitoba led the provincial government to adopt a law making English the only language of education in the province.

La Survivance

With the elimination of French education, francophones lost the last and perhaps the most important of the rights they had been guaranteed by the Manitoba Act. This initiated a period of low-key survival for the next half century. French was no longer the language of the provincial state, and francophones kept a low profile within a province which largely forgot it had ever been bilingual.

French language education continued illicitly. School inspectors routinely visited school to ensure that English was the only language of instruction. Stories of students hiding French material when the inspector came for a visit became legendary over time, although as Frances Russell notes, senior bureaucrats often turned a blind eye to French education and “…waged a continuous battle against the more zealous school inspectors…”. The Association d’Éducation des Canadiens français du Manitoba (AECFM) was created in 1916 to ensure a coordinated approach to keeping French education present in francophone communities. The AECFM was the most important francophone organization until 1968, when its mandate as assumed by the newly created Société franco-manitobaine (SFM).

The return of French education

The province of Manitoba slowly began recognizing education rights in 1955, when the province granted the right to teach French between grades 4 and 6. This was gradually expanded until the right to full French education was recognized in 1970. Battles over education continued however, and the right of the community to manage its own full-French schools was not settled until 1994 when, as the result of a Supreme Court ruling asserting the rights of linguistic minorities to control their own education, the Division scolaire franco-manitobaine was created.

The Language Crisis

Changes in education policy during the 1970s took place in the broader context of linguistic upheaval. In 1976, the same year that the Parti Québécois won their first provincial election in Québec, a francophone Métis insurance broker named Georges Forest received a unilingual English parking ticket in Winnipeg. Over three years, and facing significant opposition (even from within his own community), Forest eventually used the ticket as the basis for a successful constitutional challenge of Manitoba’s Official Language Act of 1890. In Attorney General of Manitoba v. Forest (1979), the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that the law making English the only official language of Manitoba was unconstitutional. Forest’s gamble, which had seemed so improbable in 1976, was won.

The sequel to Forest’s victory demonstrated the distance between a constitutional verdict and its application. The provincial Conservative government under Sterling Lyon moved very slowly on the issue of language. Frustrated by the lack of progress, Roger Bilodeau, a young lawyer from St. Boniface, used his own parking ticket to launch a separate case to determine whether the whole of Manitoba’s laws passed between 1890 and 1979 were unconstitutional. The issue, and the cost involved, caused considerable tension in Manitoba while the provincial NDP government of Howard Pawley, now in power, searched for a solution.

Tensions over linguistic rights rose to a fever pitch. Anti-french sentiment culminated in the fire-bombing of the offices of the SFM in January of 1983. The president of the organization was forced to move his family out of the province after receiving death threats. With no political solution in sight, the Bilodeau case moved forward. In a 1985 reference (Re Manitoba Language Rights), the Supreme Court ruled that all of Manitoba’s laws passed unilingually between 1890 and 1979 were unconstitutional.

Policy and Law

As the question of constitutional obligations wove its way through the courts, tensions gradually cooled. Returned to power in 1988 under a different leader (Gary Filmon), the provincial Conservatives enacted the first French Language Services policy in 1989. The government also commissioned a francophone provincial judge to report on French language services in Manitoba. The Chartier Report (1998) set the tone for the government of Manitoba’s approach to language rights. It focused on recognizing the constitutional right to official bilingualism in the courts and legislature while slowly putting in place government services (which were not constitutionally mandated) where the number of francophones warrants it. Fundamentally, this approach has not changed since the 1990s, and forms the basic framework on which a provincial law was created. The Francophone Community Enhancement and Support Act, passed in 2016 with unanimous approval of the legislature, embeds pre-existing rights and policies in legislation without radically altering or adding to them. Significantly, the law was passed with no opposition and virtually no attention from the English-speaking majority. French language rights have become an accepted and largely uncontroversial part of the political landscape in Manitoba.

Education and Culture

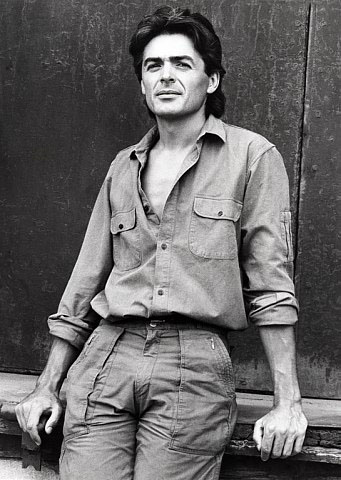

Fully French education in Manitoba is offered through the Division scolaire franco-manitobaine, which has 24 schools and one adult learning centre spread throughout the province. A growing number of parents are also choosing to enrol their children in immersion schools. Post-secondary college and university education is available through the Université de Saint-Boniface. Along with Radio-Canada stations on television and radio, the community maintains a weekly paper, La Liberté, and a community-run radio station, Envol 91.1 FM. Le Cercle Molière, the oldest continuously running theater company in Canada, performs plays in French. The community maintains a significant interest in its heritage and culture, perhaps most visibly through the Saint Boniface Museum and the Festival du Voyageur, Western Canada’s largest winter festival. The vibrant francophone artistic community hosts film festivals, art exhibits, cultural celebrations, and numerous music events throughout the year. The community has produced some notable artistic successes, such as author Gabrielle Roy and singer Daniel Lavoie. National Hockey League player Jonathan Toews is also from the francophone community, and is a graduate of Collège Louis Riel.

Demographics and Politics

The francophone population of Manitoba has remained relatively stable for several decades, hovering around 5 per cent, although the most recent census demonstrates a decreasing number of francophones speaking the language at home. In the 2016 census, 40,525 (3.3 per cent of the population) indicated French as their mother tongue. That said, the way that minority language communities are counted for statistical purposes is a point of contention in Manitoba as it is elsewhere in Canada. This is mainly because the category of people with French as their “mother tongue” exclude francophones who have learned French as an alternate language. The expanded definition of “francophone” in provincial law further complicates traditional ways of counting linguistic vitality. While the number of people speaking French at home declined, for example, the overall bilingual capacity of Manitobans remained stable at 8.6 per cent of the population.

Francophones in Manitoba are clustered in the south, with 90 per cent of the French speaking population living in Winnipeg or within an hour’s drive of the city. Corridors of traditionally French towns run south and south-east, following the Red and Seine rivers respectively, and north-west towards Lake Manitoba. Small clusters of francophones can also be found in various other parts of the province. Within Winnipeg, the traditionally francophone Riel district encompasses the south-east portion of the city, including the neighbourhoods of Saint-Boniface, Saint-Vital, and Saint-Norbert.

Manitoba’s francophone community has also produced a number of political figures on the provincial and national stage. This includes federal Cabinet ministers such as Ronald Duhamel and Joseph-Phillipe Guay. Manitoba has also traditionally been represented by one francophone Senator in the Canadian Senate. This notably included Maria Chaput, who led repeated efforts to change the way francophones are defined and counted for census purposes.

Here again definitions complicate matters. Former Heritage Minister Shelly Glover learned French as a second language and identified as a francophone, while former Manitoba Premier Greg Selinger also served as Minister Responsible for Francophone Affairs and identified as a Francophile. Since 2001 the SFM has also had a strategy in place to recruit French-speaking immigrants from non-traditional sources, which has resulted in an increasing number of francophones from West and North Africa immigrating to Manitoba (see African Canadians). These individuals and others like them represent the changing face of Manitoba’s Francophonie.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom