Childhood and Adolescence

Like thousands of other Irish fleeing the Great Famine of the late 1840s, John Barry immigrated to Canada. In 1851, he married Aglaé Rouleau, of L’Isle-Verte. Robertine, the ninth of their 13 children, spent part of her childhood in Les Escoumins, where her father managed the largest sawmill on the Upper North Shore of the St. Lawrence. When he retired in 1873, the family moved to Trois-Pistoles, and Robertine became a boarding student at the Sœurs Jésus-Marie Convent. She later continued her studies with the Ursulines in Québec City.

When Barry finished school in 1882, she wanted to become a journalist, even though that profession’s status as a male preserve made her ambition seem unrealistic at the time (see Journalism). In French-speaking Canada, there were no female journalists, and elsewhere in the world, female journalists were regarded as “loose women.” For that matter, any middle-class woman who worked was seen as lowering herself and dishonouring her family. But Barry turned a deaf ear to any disparaging remarks. When her fiancé failed to support her plans, she broke off their engagement and began proposing articles to several publishers. Only one agreed to publish her articles, but on the condition that her by-line not appear on them. She refused defiantly: “If I write it, I sign it!”

While awaiting a more favourable response from other publishers, she suggested to her sister Évelyne that they write a novel together, but Évelyne chose to become a nun instead. Robertine, on her parents’ advice, began teaching music at a convent in Halifax to see whether she wanted to enter holy orders too. But that proved not to be the case, and she returned to Trois-Pistoles.

Journalism Career as “Françoise”

Over the following years, Barry approached many publishers, but not until 1891 did she find one open-minded enough to want a woman on his team of journalists. His name was Honoré Beaugrand, and he was the editor of La Patrie, one of the great newspapers of the time. Not only did he hire her, but he also decided not to confine her to the “women’s pages,” as remained the practice for female journalists at other newspapers for years to come. Instead, he gave her the same kinds of assignments as her male colleagues. Even better: he published her weekly column, Chroniques du lundi, on his front page. There, writing under the pen name Françoise, she addressed all the major issues of the day: women’s suffrage; social justice; the need for shelters for the poor, the elderly, and female victims of family violence; legislation on child labour; the founding of public libraries; and non-confessional education and the creation of a provincial ministry of public education (see History of Education). She demanded what no French-Canadian woman had ever demanded publicly before: that woman be allowed to attend university and practice the same professions as men (see Women and Education).

Though many of Barry’s readers and fellow journalists appreciated and praised her work, others felt that journalism was no place for a woman, mocking her as a frump and referring to her as “Monsieur.” She had numerous run-ins with Henri Bourassa, the notorious antifeminist who founded the newspaper Le Devoir in 1910.

In those days, women also were not supposed to take a public stance on politics, but that did not stop Robertine Barry. She asserted her own patriotism and vigorously denounced the clergy’s efforts to intimidate Quebecers who sided with the Liberal Party. She openly attacked the Catholic Church for spreading the idea that religion would be persecuted “if the Liberals emerged victorious from the fray” and that anyone who voted for them would be damned for eternity and might even be denied the right to a Catholic burial. She was also outraged when she learned that priests were refusing to hear women’s confessions if their husbands voted for Liberal candidates.

Author and Lecturer

Every Thursday, Barry held a salon where she hosted bohemians and free thinkers. A fascinating woman, Barry defied convention: she rode a bicycle, walked alone through the streets at night, and travelled without an escort (all considered scandalous behaviours for a woman at that time) and defended controversial positions, such as the joys of celibacy. Over the years, she became more and more highly regarded for her talent as a journalist. She contributed to several newspapers and magazines, including La feuille d’érable, Bulletin, Le coin du feu, La revue nationale, Franc-parler, La Presse, Samedi, La Revue canadienne and Almanach du Peuple (see Newspapers). Yet she still found time to sponsor charity fairs and chair fundraising campaigns.

In 1895, Barry published a collection of stories, Fleurs champêtres, which was launched at Château Ramezay in Old Montreal. The critics’ response to the collection was ecstatic; they compared her with towering French authors George Sand and Honoré de Balzac. But there was one discordant voice: Jules-Paul Tardivel, the ultramontane founder and editor of La Vérité, who chastised her for having neglected religion in her book. He was convinced that she was under the evil influence of her colleagues, and in particular her boss, Honoré Beaugrand, a freemason and avowed anticlerical.

In 1899, a time when married women had to get their husbands’ permission before speaking publicly, Robertine Barry became the first woman invited to lecture at the Québec City branch of the Institut canadien. She continued to lecture there for a number of years, donating the proceeds to charity.

In 1900, Barry published a collection of 87 of the weekly columns that she continued to write for La Patrie. She also began writing for this newspaper’s women’s page, Le coin de Fanchette, as well as penning the first advice column in Quebec, initially entitled Réponses aux correspondants and later Causerie fantaisiste.

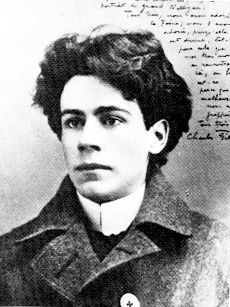

Nelligan and Paris

In 1899, rumours began flying that Montreal poet Émile Nelligan had fallen in love with Robertine Barry, even though she was 16 years his senior. The handsome young poet visited her frequently at the home on Rue Saint-Denis in Montreal where she had been living with her family since 1891. There he would read his poems out loud to her, and she would listen and advise him. She was one of the first to recognize his talent. In the poems that he dedicated to her, he seems to cry out first his love for her, then his anger at her having spurned him. She placed part of their correspondence and a few of his poems under lock and key, perhaps considering them too compromising to be published.

In August 1899, suffering from mental illness, Nelligan was placed in an asylum. Barry was there to provide support to his mother Émilie, who was also her friend, but soon had to leave for Europe: Canadian prime minister Wilfrid Laurier had appointed her to represent Canadian women at the Paris International Exhibition and the International Women’s Congress held in conjunction with it. For distribution at this exhibition, the Canadian government had published a book entitled Women of Canada: Their Life and Work, to which Barry contributed a chapter on Canadian women in literature. Her “Letters from Françoise”, in which she wrote about her stay in Paris from April to September 1900, were published in La Patrie.

Le Journal de Françoise

Upon returning to Montreal, Barry fell ill with typhoid fever, but fortunately recovered after a few weeks in hospital. She then began thinking about publishing a bi-monthly magazine. She had enough contacts, both in France and in Quebec, to find talented contributors and give women the opportunity to be published. She put out the first issue of her new magazine, Le Journal de Françoise, on 29 March 1902, with no funding apart from her own savings. Her contributors included writers, journalists, notaries, judges, doctors and politicians. Over the years, Le Journal de Françoise published over 500 different authors, including Juliette Adam, Jules Claretie, Edmond de Nevers, Albert Lozeau, Laurent-Olivier David, Marie Gérin-Lajoie, Éva Circé-Côté and Louis-Honoré Fréchette. Fréchette called her his “literary godmother”, and it was thanks to her help that he began his career in journalism in Montreal.

Professional Associations, Theatrical Success and Academic Awards

In 1904, Robertine Barry attended the St. Louis World’s Fair along with 15 other Canadian women journalists, including Grace Denison, Kathleen Coleman, Anne-Marie Huguenin (pen name: Madeleine) and Kate Simpson Hayes. Together they founded the Canadian Women’s Press Club, of which Barry was elected vice-president. She also served as president of the Association des femmes journalistes canadiennes-françaises (Association of French-Canadian Women Journalists) and received a number of Academic Palm awards from France’s Ministry of Public Education.

In 1905, Méprise, a play that Barry had written, premiered at Montreal’s Salle Karn, and Prime Minister Laurier made a special trip from Ottawa to attend. The play received critical acclaim. In Le Canada, one journalist wrote that “Montréal’s entire intellectual élite applauded this witty comedy by ‘Françoise’.”

In 1906, Barry represented the Canadian government at the Milan International Exhibition. Accompanied by her sister Caroline, she took advantage of this trip to Italy to meet the Pope in Rome. She also stayed at the luxurious Paris headquarters of the prestigious Lyceum Club for women interested in arts, letters, and science, of which she was a member.

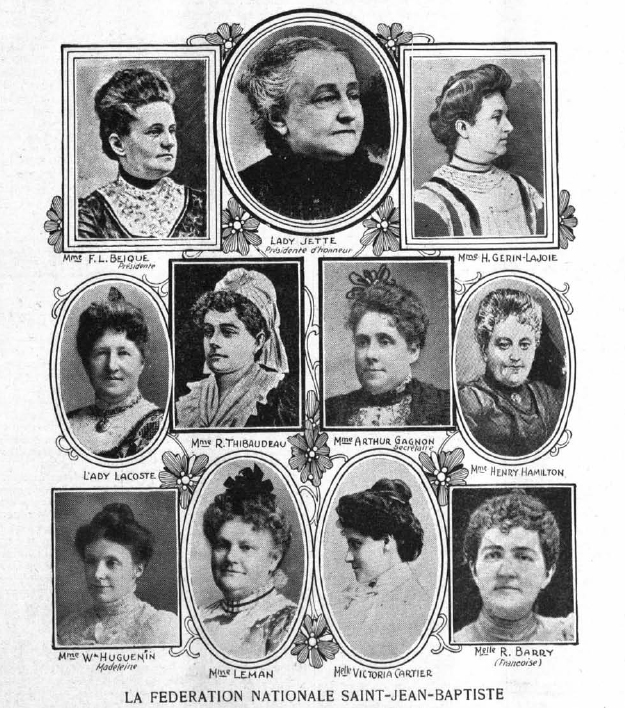

Fédération nationale Saint-Jean-Baptiste

Robertine Barry was a founding member of the first French-Canadian feminist association, the Fédération nationale Saint-Jean-Baptiste (FNSJB), of which Marie Gérin-Lajoie was president (see Women’s Organizations). Barry was on the committee in charge of organizing a school of home economics. Along with Marie Gérin-Lajoie and Joséphine Marchand-Dandurand, she was also involved in founding Quebec’s first collège classique (classical college) for women, the École d’enseignement supérieur. In 1926, this institution became the Collège Marguerite-Bourgeois, providing the first education program to prepare Quebec francophone women to attend university.

At the FNSJB congress in 1909, Barry gave a speech on journalism and popular education, in which she observed that journalists were among society’s leading educators, but that unfortunately, newspapers were the only university to which women had access. In this same speech, she also lamented Quebec’s lack of proper public libraries. Unlike the other speakers, she said nothing about faith, religion, or women’s role as good wives and mothers. Afterward, FNSJB president Marie Gérin-Lajoie wrote the Archbishop of Montreal, Paul Bruchési, to ask whether “the conscience of the women who lead the Federation would be blotted with a sin if they allowed Miss Barry’s speech to be published.” He wrote back to say that while publishing it would not be a sin, this speech was “false as a thesis, very incomplete and absolutely outside the bounds of the Christian idea.” In another letter, he added that newspapers must “draw their inspiration from truth, religion and virtue.” As a result, Barry’s speech was never published in the proceedings of the congress.

The End of an Adventure

On 15 April 1909, after a seven-year run, Barry ceased publishing the Journal de Françoise, which had become a massive drain on her finances. Likely because of her past frequent efforts to improve women’s working conditions, Québec premier Lomer Gouin appointed her the first female inspector of women’s working conditions in factories. But she found this work unsatisfying and fell into a depression, Her doctor recommended travel, so she made a trip to Paris, where she had numerous friends, including many celebrated men and women. When she returned to Montreal, however, her health was no better, and she died a few months later, of a stroke. She was only 46, but she had lived a full life.

Robertine Barry is buried in Section R of the Notre-Dame-des-Neiges cemetery in Montreal. Her grave is grass-covered and unmarked, with not even a small cross to show the final resting place of this pioneer of women’s journalism. This anonymity reflects the way that her memory has been forgotten.

Recognition

Three months after her death, a performance of Barry’s play Méprise was given at a literary and musical soirée at Château Frontenac in Québec City. In 1930, Barry’s one other play, Souliers de bal, was performed, starring Sita Riddez and Marie Dugal, her niece.

In 1936, in a conversation broadcast on radio, a group of women recalled Robertine Barry’s courage and expressed their gratitude to her for having defended women’s rights and blazed the trail for women to work in journalism. The Robertine Barry Prize, established in her honour by the Canadian Research Institute for the Advancement of Women, was awarded annually from 1984 to 2000, to the author of an article on the status of women. In 2021, Barry was designated a historic figure by the Ministère de la Culture et des Communications du Québec.

A classroom at Collège Marie-de-l’Incarnation in Trois-Rivières bears Barry’s name, as do two streets, one in Montreal and the other in Baie-Comeau, Québec. Commemorative plaques in her honour have been unveiled in the Quebec villages of L’Isle-Verte and Les Escoumins, where she lived as a child.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom