Indian Day Schools were racially segregated educational institutions that operated in Canada from the late 19th century until 2000 (see Racial Segregation of Indigenous Peoples in Canada). These schools were intended to assimilate Indigenous children into mainstream Canadian society by eradicating their cultural practices, languages and traditions. More than 150,000 Indigenous students attended these institutions. The Indian Day School system was closely linked to the larger residential school system. However, there are important distinctions between the two, namely that students were educated in their own communities and returned home to their families at the end of each day. In 2019, a significant milestone was reached with a $1.47 billion class action settlement involving approximately 200,000 survivors. However, criticisms of the settlement process persist. Survivors have led efforts to support language revitalization, healing initiatives, commemoration efforts and truth-telling projects. Their efforts acknowledge the need for reconciliation and addressing the historical injustices inflicted upon Indigenous communities.

Operation of Indian Day Schools

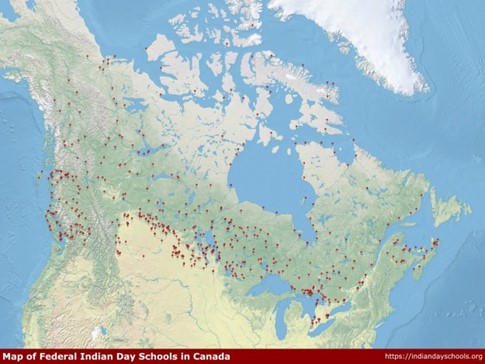

Similar to residential schools, the Roman Catholic, Anglican, Presbyterian, Methodist and later United churches operated these institutions. The federal government provided the funding. In total, over 699 Indian Day Schools operated on nearly every Indigenous reserve in Canada. The only exception was within the province of Newfoundland and Labrador.

The progression of the system occurred at different times throughout the development of Canada. Students’ experiences of the schools differed depending on when they attended. For example, on Baffin Island in Arctic Bay, the first Protestant Indian Day School did not open until 1 September 1958. On the other hand, the history of some day schools along the north shore of Lake Ontario can be traced back to the late 1700s. By 1920, attendance at day schools was compulsory. Indian agents could remove children from their homes if they did not attend regularly.

Objectives and Curriculum

The primary objective of Indian Day Schools was to assimilate Indigenous children into Euro-Canadian culture by eradicating their Indigenous identity. The curriculum in these schools focused on teaching English or French, Western academic subjects and Christian religious teachings. Indigenous languages, cultural practices and traditional knowledge were actively discouraged or suppressed. The goal was to create a homogeneous Canadian society that adhered to Eurocentric norms and values. As Canada’s industrial economy grew, the schools’ mandate changed to a focus on manual training to create productive workers.

The schools were typically one-room schoolhouses. Several grades were taught together, similar to the rural schools of that period. There was typically no running water, a wood stove for heat and the basic necessities of education were carefully tracked (e.g., number of chalk or pieces of paper). The schools had a strict list of textbooks that could be included within the learning. Typically, they followed the local provincial curriculum’s content.

Teaching salaries were also the lowest of any educational system in the country. These positions attracted a wide range of unqualified teachers. Students would return to their homes after school hours. This allowed them some level of connection with their families and communities. However, this also meant that the students faced cultural conflicts. They had to navigate between their traditional upbringing at home and the assimilationist education they received at school.

Abuse and Death

Widespread physical, sexual and cultural abuse occurred across the system with lasting impacts on Indigenous communities. In Curve Lake First Nation, one survivor remembers the strap and said, “When I got it, I had to stand in front of all of them and take it… And they would try and strap you until you came to tears. And to this day, I don’t cry.” In Kahnawà:ke Mohawk Territory, another survivor recalled, “You were always hit with something: straps, pieces of wood, rulers, yardsticks, chalk thrown at you, erasers thrown at you, you were pushed around.” On the West Coast, a survivor from the Gitanyow Band in British Columbia said, “I have permanent nerve damage in my back because of the strapping, from cringing all the time.” According to APTN news, an analysis of records representing only 14 per cent of the Indian Day School system – 46 day schools out of the total 699 – found that 200 Indigenous children died from their time at these schools. This indicates that the total amount of deaths in these institutions is likely much larger. Students were constantly at risk of catching diphtheria, chickenpox, measles, tuberculosis and other respiratory illnesses.

Indian Day School Class Action Settlement

After being left out of the 2006 Indian Residential School Settlement Agreement, Indian Day School survivors across the country organized a class action lawsuit against the federal government. It was launched in 2009. In 2019, the Canadian government settled the suit with approximately 200,000 survivors of the day school system for $1.47 billion.

Compensation ranged from level one ($10,000 for attending one of the schools) up to level five ($200,000 for repeated verbal, sexual or physical abuse). To obtain the higher levels of compensation, survivors were required to write their claims. This can be a triggering and damaging process for those living with long-term injuries. By July 2022, approximately 185,000 survivors had submitted claims. Around 70 per cent of those claims have been within level 1.

Controversy

The settlement, specifically the way it was handled by the federal government and a private law firm, was met with severe criticism. Six Nations of the Grand River had the most Indian Day Schools in Canada at approximately 18. Chief of Six Nations Mark Hill has repeatedly asked for an extension to the settlement process to allow survivors time to make their claims and work through the processes.

Reopening the claims settlement for all IDS survivors is not a cure for the harm inflicted, but it is the least disruptive and fairest solution to a settlement agreement meant to address some of the most horrific abuses in Canada’s history. Anything less is not fair, reasonable, or in the spirit of reconciliation.

Chief Mark Hill

He has now presented this case to the Supreme Court. In 2023, a Federal Court denied the motion to have the deadline for claims extended.

As part of the settlement agreement, survivors have launched the McLean Day Schools Settlement Corporation (MDSSC). This organization is tasked with administering a $200 million legacy fund, from the $1.47 billion settlement, intended to support projects on “language & culture, healing & wellness, commemoration, and truth telling.” Truth telling remains a challenge as church organizations have been reluctant to provide full archival access to their records.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom