Background

Beginning in the 1830s, colonial leaders in what would become Canada recognized that they needed railways within and between their colonies to improve communications, grow economically and improve military defense capabilities. The first small railways were built in the 1850s. At the 1864 Confederation conferences in Charlottetown and Québec City, delegates from Nova Scotia and New Brunswick stated that their joining Canada was dependent upon the construction of intercolonial railways. Railway construction began shortly after Canada became a country in 1867 and, by 1876, rail lines linked a number of cities, resources and ports.

In the 1830s, Canada was made up of hundreds of Indigenous nations and six British colonies: Upper and Lower Canada, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland. The colonies were isolated from one another. The island colonies (PEI and Newfoundland) were separated by water and the others by thick, vast forests and rivers roiling with untamed rapids. Dirt roads were muddy in spring and dusty in summer, with most routes between towns little more than rough wagon ruts. Travel was easiest in winter, huddled beneath buffalo robes in horse-drawn sleighs. Letters were the only form of communication, and delivery could take weeks between colonies.

Technology met the need for better transportation and communications in 1825 when, in Britain, George Stephenson unveiled the Rocket. It was the world’s fastest and most powerful steam-powered locomotive, capable of moving freight and people at what was considered an unfathomable speed: 58 km per hour. This was faster than any human had ever travelled because it was faster than a horse could run.

The new and rapidly advancing train and rail technology excited British North American colonial leaders. The poor and debt-ridden colonies hoped to link their towns and reap the economic benefits of tying mines and sawmills to shipyards and ports. If rail lines could run between the colonies, then all could see greater economic opportunities through increased intercolonial trade. Canadian business people were excited by the possibility of boosting sales of their agricultural and manufacturing products by connecting to maritime markets and Britain through access to the year-round, ice-free ports of St. Andrews, Saint John and Halifax. Only a generation before, the War of 1812 had seen the United States invade the colonies. Railways would make borders more defensible by enabling the quick movement of troops and weaponry.

Impetus for the Intercolonial Railway

An 1836 delegation to London was favourably received. British army engineer Captain Yule was dispatched to survey a possible rail route. Progress was halted in 1842, when the United States and Britain signed the Webster-Ashburton Treaty. Among its provisions was the establishment of the Maine-New Brunswick border. It left much of Yule’s proposed route on the American side of the new border.

British Colonial Secretary William Ewart Gladstone surrendered to the continuing pressure from colonial leaders and sent engineers to undertake a new survey of potential rail routes. They proposed several lines, but warned that each would be expensive, involve many steep hills and numerous bridges. American railway interests proposed ignoring the intercolonial line and instead connect New Brunswick and Nova Scotia to the United States through Portland, Maine. There was a struggle between those wishing to make quick profits with the American line and those wanting to maintain British political and economic connections. By 1860, only two small rail lines had been constructed: one in Nova Scotia that joined Truro and Halifax (opened 1858); and another in New Brunswick, linking Saint John and Shediac (opened 1860).

The American Civil War began in 1861. While Britain and its North American colonies were officially neutral, the war’s effects spilled over the border. When an American ship stopped, and then took two southern American officials from Trent, a British ship, a British-American war that would begin with an invasion of the British colonies seemed imminent. The need for an intercolonial railway was emphasized when British soldiers arrived in Halifax and Saint John, but there was no way to quickly transport those assigned to the Province of Canada. The soldiers ended up plodding north in a long line of horse-drawn sleds.

The Trent Affair was peacefully resolved. Nova Scotia Premier Joseph Howe and New Brunswick Premier Samuel Leonard Tilley happened to be in London at the time. In meetings with British officials, they used the crisis and troop movement debacle to stress the need for an intercolonial railway. They also spoke of the need for a rail route to move people and goods between Canada and the Maritime colonies that avoided travelling through or even close to the United States.

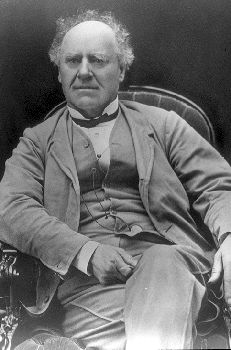

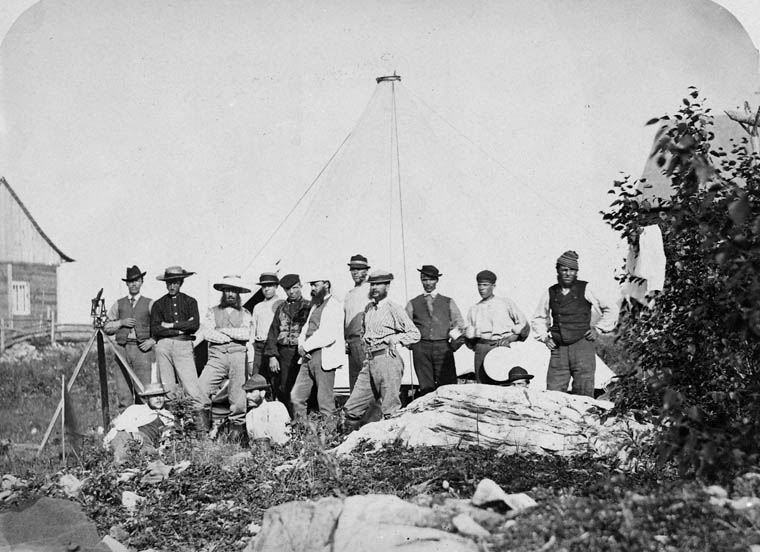

The Trent Affair, and the appeals of the colonial leaders, led to the granting of a British loan guarantee to fund new research regarding possible intercolonial rail lines. In 1863, talented engineer Sandford Fleming began rail survey work in the dense forests of New Brunswick.

Confederation

While Fleming worked, it became increasingly clear to colonial leaders that Britain was becoming less willing to continue its economic and military support, and that the United States remained a threat. The economic, political and military situation for all of the colonies was dire, and drastic action was needed. Representatives from the Province of Canada, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island met in Charlottetown in September 1864 for the first Confederation conference (see Charlottetown Conference). The Maritime colonies quickly abandoned their idea of amalgamating themselves into a single colony. Instead, they approved the notion of uniting with Canada to form a new country. The representatives discussed the manner in which the Canadian state would be constitutionally structured, but one of the main topics of conversation was railway construction.

PEI was opposed to the idea of spending money on railways from which it would derive no benefit. Nova Scotia and New Brunswick delegates, on the other hand, declared that the building of intercolonial rail lines was a precondition of their joining Canada. They warned that they could take the still pending American offer or build more lines on their own without joining the Canadian project. Meanwhile, Canadian delegates, especially Montréal’s influential Alexander Galt, spoke passionately about using a railway not only to join the Maritimes to Canada but to extend the new country north and west to the prairies. A few weeks later, in Québec City, delegates finalized their plans for the new country, which included the building of rail lines ( see Québec Conference). Largely because they saw no value in railway expenditures, PEI and Newfoundland, which sent delegates only to the Québec Conference, refused to join Confederation. But the others agreed to unite.

Charting the Intercolonial Railway

While the legislatures of Canada, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick were debating and ratifying the Confederation deal, Sandford Fleming issued his report on the best intercolonial rail routes. He proposed three lines, but argued for what he called the Chaleur Bay route. He argued that it would be the most economically viable. It would join the manufacturing centres of Montréal, Kingston and Toronto to maritime towns and ports, pass through New Brunswick lumber and fishing towns, and Nova Scotia coal mining and shipbuilding communities. Plus, it would all be a safe distance from the American border. Colonial leaders were pleased with the proposal, which they approved.

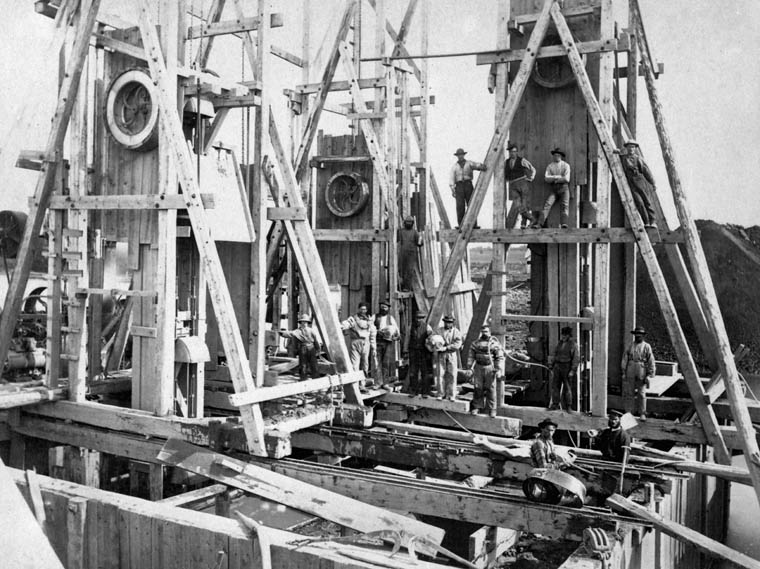

Construction

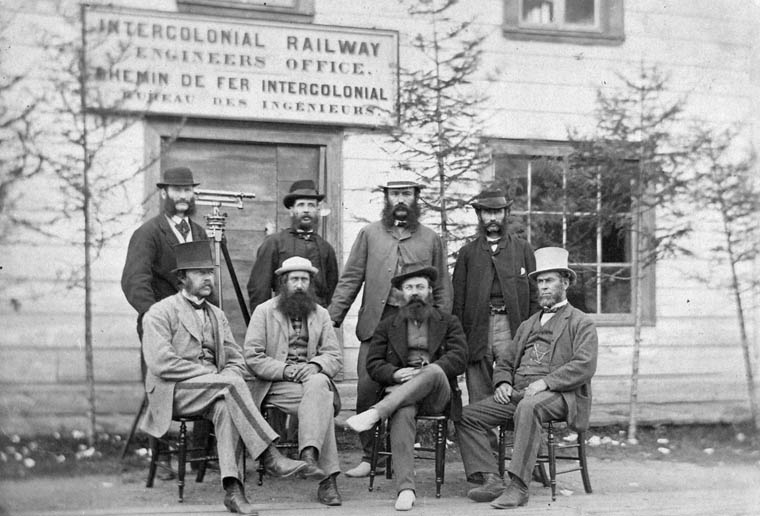

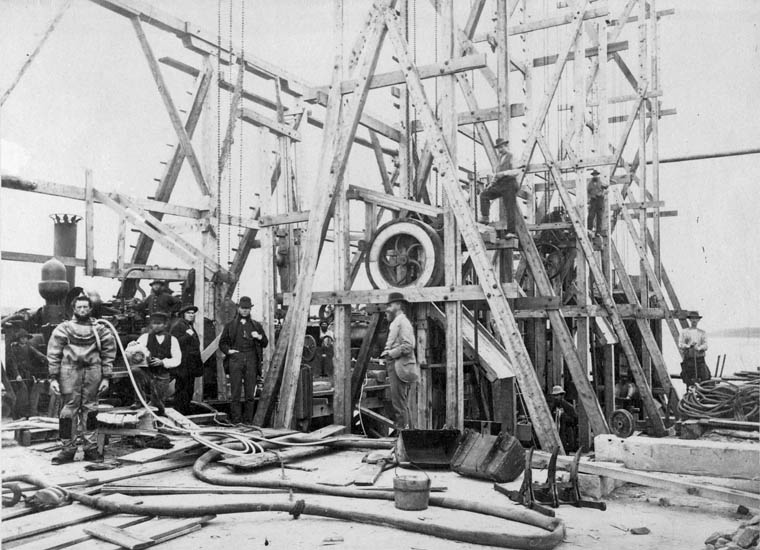

Canada became a country on 1 July 1867. Shortly afterwards, Fleming was appointed engineer-in-chief and assigned the task of leading the construction of his proposed railway route. It would be Canada’s first national infrastructure project. By November 1872, the first section was running between Amherst and Truro, Nova Scotia. Two years later, trains were moving along the south shore of the St. Lawrence River between Rivière-du-Loup and Mont-Joli, Québec. In July 1876, Fleming declared the line’s final section, between Mont-Joli and Campbellton, New Brunswick, to be open. This completed the line from Québec, through the rail hub at Moncton, to the Bay of Fundy and then through Truro to Halifax. The 1,100 km line was a technical marvel that used the latest technology and construction methods to keep the rail lines straight and level and with nearly all bridges made not of wood, as was the custom of the day, but the far safer and more durable iron.

With the completion of the line, Canada’s Department of Railways and Canals assumed responsibility for its operation. Work continued to tie in several branches of lines that had been constructed by the provinces. Soon, southwestern Ontario, Toronto and Ottawa were tied by rail to Montréal and Québec City, and to towns in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. Communities along the routes thrived due to rail traffic and employment opportunities that grew with it, while those that had been passed by saw progress stall. To stimulate economic growth and interprovincial trade, federal government regulations kept rail freight rates low. In 1919, the old intercolonial railways were incorporated into the Canadian National Railways Company.

Significance

Railways were as significant in the 19th century as canals were in the 18th century and highways were to the 20th century (see Railway History); they were essential to communications, transportation, defence and commerce. The Intercolonial Railway linked ports, towns and provinces, helped build the country and became an essential expression of Canada’s nationhood.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom