Kateri Memorial Hospital Centre (KMHC) is a healthcare facility located in Kahnawà:ke, Quebec. Then known as Hôpital du Sacré-Cœur de Caughnawaga (Sacred Heart Hospital of Caughnawaga), it was established in 1905 by Adele Perronno. Initially, the funding to support the hospital came from the Jesuits, a private donor, the federal government, and later the Quebec government. The hospital is named after Saint Kateri Tekakwitha and has served the community for over 100 years. It is unique for a number of reasons. First, it is run by a Board established by the Mohawk Council of Kahnawà:ke. Secondly, it is a hospital located within a First Nations community. Finally, the new buildings were constructed following nation-to-nation discussions and agreements with the Quebec government. Beginning in 2015, the hospital underwent an estimated $31 million expansion and renovation. It provides various healthcare services, including clinics and a long-term care home. The community takes great pride in the hospital, viewing it as a symbol of their resilience.

Kahnawà:ke

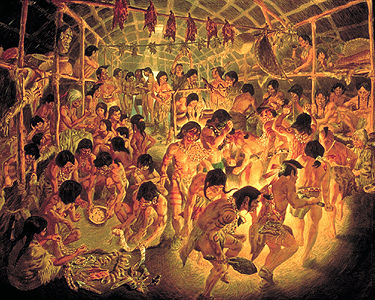

The Mohawks of Kahnawà:ke are a Haudenosaunee community located in Quebec’s geographic boundary. The community has an elected council. Kahnawà:ke has a rich history of activism, resistance against colonialism and pursuit of Indigenous peoples' rights in Canada.

The land base upon which Kahnawà:ke is situated was historically established following settler arrival through the seigneurial system (Seigneury of Sault St. Louis). This system has been a factor in land claims involving Kahnawà:ke and the community’s complex relationship with the Jesuits.

Additionally, the community's relationship with municipal, provincial and federal governments has been complex. The community has challenged the governments when a Quebec municipality planned to expand a golf course and develop townhomes on top of a Kanyen’kehà:ka (Mohawk) grave site near Kanesatake, Quebec. The overall tension between Kanyen’kehà:ka of Kanesatake and the governments led to the Kanesatake Resistance (Oka Crisis). Kahnawà:ke supported the action by demonstrating solidarity with Kanyen’kehà:ka of Kanesatake by erecting barricades, providing resources and participating in public demonstrations. This crisis and the failure of the Meech Lake Accord led to the establishment of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP), in which the community participated. The RCAP contributed to the establishment of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. This was significant for Kahnawà:ke, as well as other First Nations communities, when considering the legacy of residential schools and Indian Day Schools in Canada.

Key Periods in KMHC’s History

There are many significant factors influencing the Kateri Memorial Hospital Centre (KMHC) throughout its development. Canadian health policy has been closely connected to significant historical events, including the Great Depression and both World Wars (see also First World War; Second World War). These events and policies as well as historical events within the broader Kahnawà:ke community have impacted KMHC’s operations and development.

Religious Leadership

The Hôpital du Sacré-Cœur de Caughnawaga (Sacred Heart Hospital of Caughnawaga) opened in 1905. According to the hospital’s history book by Lori Niioieren Jacobs (2005), the hospital was managed by Adele Perronno with three nurses. The hospital history book states that Perronno proposed the idea of a hospital to the people of Kahnawà:ke. She was initially met with opposition, but the hospital was approved on several key conditions. One condition was that the land had to revert to the community when the nurses left. Additionally, the band would not be responsible for the maintenance of the building. Finally, there was an understanding that no nuns would be brought into the community. The first two conditions were in writing, while the last was not. In addition to Perronno and the nurses, various physicians came and went from Montreal.

In the early 20th century, many First Nations faced challenges with overall health and well-being. These challenges were commonly associated with poor living conditions and a lack of medical facilities within First Nations communities. These challenges included high death rates due to tuberculosis, influenza, pneumonia or bronchitis, and malnutrition.

Near the end of the First World War, some soldiers returning to their home countries brought the Spanish flu. The Spanish flu pandemic killed between 17 and 100 million people worldwide and posed an increased risk to First Nations, Métis and Inuit communities in Canada. The flu significantly impacted urban centers such as Montreal, approximately 15 km north of Kahnawà:ke. At the time, the distance between Montreal and Kahnawà:ke was easily traversed by boat across the St. Lawrence River and by train. Not only did the Spanish flu have a greater risk or impact on the First Nations populations, but it also affected other residents within those communities, including healthcare workers like Perronno and the nurses.

In 1919, around the age of 80, Perronno retired. This was at the same time Canada was witnessing the birth of its first Department of Health (now Health Canada). The Department of Health was established as the federal government recognized the need for a coordinated public health response to the pandemic. Despite promises made during the proposal for the hospital that nuns would not be brought in as nurses, responsibility for the hospital was transferred to L’oeuvre de Protection des Jeunes Filles, a religious order of nursing nuns, after Perronno’s retirement. In 1955, these nuns left the community, citing financial difficulties. They reportedly took most of the hospital's assets with them, leaving only the beds occupied by six remaining patients. These patients received care from a physician appointed by the federal government and assistance from local volunteers, including volunteer nurses. According to the hospital’s history book by Lori Niioieren Jacobs (2005), the sisters sued the federal government for the capital and infrastructure funding they had invested in the building over the years, totalling $35,000. Ultimately, the government settled for $10,000 out of court.

Indigenous Control and Search for Government Funding

The period following the nurses’ departure continued to be challenging for KMHC staff and the broader Kahnawà:ke community. The role of the Indian agent within First Nations and the significant control they exerted over funding and other administrative aspects impacted the KMHC. Additionally, there was jurisdictional complexity for the parties involved. The KMHC intersected the province's constitutional responsibility for healthcare and the federal government’s responsibility for First Nations people.

Despite the hospital's many challenges, the community pitched the idea of a separate community-run Kateri Health Centre to the federal government. This new centre opened in 1970, while a plan was developed for a new hospital building, eventually erected by 1986. Between 1970 and 1986, the community worked diligently to negotiate and construct the new hospital centre.

Overlapping federal department jurisdictions impacted the search for funding for the new hospital. While the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development was responsible for First Nations people, it wasn’t directly responsible for their health (see also Federal Departments of Indigenous and Northern Affairs). Health was the responsibility of National Health and Welfare. One of the complexities was that the Quebec government would not fund capital projects in First Nation communities due to jurisdiction. The hospital would cross provincial and federal jurisdictions, as it would theoretically be a provincially funded hospital sitting on federal land reserved for the Mohawks of Kahnawà:ke. This would mean the hospital could never be owned or operated by the province and would detract from the community’s persistent stance on self-government and local control.

The problem for the federal government is that the Constitution only assigned responsibility for managing healthcare institutions under the control of the Canadian Armed Forces. Former KMHC board member Myrtle Bush has stated, in the hospital’s history book, that the Assistant Deputy Minister for Health and Welfare at the time told the KMHC board that the federal government was “no longer in the hospital business.”

Both levels of government discussed these and other jurisdictional issues. They decided there could be cost sharing; however, the hospital would remain the jurisdiction of the province. In 1978, the Quebec government proposed a pathway of incorporation by either the hospital board or the MCK for legal administrative purposes. Incorporation would mean establishing an artificial person to represent the hospital. This would allow the hospital to issue bonds for construction that the Quebec government could redeem. Additionally, it would remove what lawyers for the Quebec government considered legal ambiguity and would clarify the applicability of Quebec labour laws. However, MCK felt that the creation of an artificial person would detract from the identity of the community. The issues of incorporation and provincial jurisdiction over the hospital stalled negotiations for several years.

On 3 July 1976, the Quebec government recognized Kahnawake Mohawk Indian Band as existing under federal law. The government also recognized that it operated KMHC and that it was within the geographical bounds of Quebec. In 1978, the government passed legislation that recognized the hospital as being part of the healthcare system, but KMHC was exempted from administrative requirements. By 1982, the KMHC established itself as a vital healthcare institution in Kahnawà:ke.

Transformation and New Building Construction

From 1984 to 2019, the KMHC underwent significant transformations. In 1984, the KMHC was recognized through the negotiation and signing of an agreement to build and operate a new hospital. This agreement was signed by representatives from the MCK and the Quebec government, including Quebec premier René Lévesque, during a public meeting in 1984 in Kahnawà:ke. It was supported by legislation from the Quebec government. This legislation, as well as a band council resolution, reflects, among other things, the broader changes towards ongoing Indigenous self-determination and self-governance in Canada. The intention through the entering of the agreement, and the legislation and band council resolution that followed, was to secure the construction of a new hospital. The hospital was built within two years and five months and was marked by ceremony in 1986.

The 1990s marked significant events, such as the Kanesatake Resistance (Oka Crisis) in the summer of 1990, highlighting Indigenous resistance and the quest for self-determination (see also Indigenous Political Organization and Activism in Canada). These events took place alongside ongoing discussions about Quebec separatism. The period is further marked by the temporary suspension of the Executive Director position and Board of Directors and the introduction of an ombudsperson at KMHC.

From 2015 to 2019, the facility underwent a three-phase expansion and renovation. As a result of this renovation, the centre became a state-of-the-art facility months before the COVID-19 pandemic. The KMHC has experienced similar challenges faced in the broader healthcare sector, namely difficulties with health and human resource shortages, infectious diseases (COVID-19, etc.) and antibiotic-resistant bacteria. It has worked to address these issues with appropriate strategic planning, staff training, accreditation and innovation, building upon the work of the many decades filled with volunteers and community support.

The MCK has established agreements with the Quebec government that spans various domains of life, including labour, economic development and registering births, social services, health and long-term care, marriages and deaths.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom