Lady Elizabeth Louise Mary Monck, Viscountess Monck of Ballytrammon, viceregal consort of British North America from 1861 to 1867 and viceregal consort of the Dominion of Canada from 1867 to 1868 (born 1 March 1814; died 16 June 1892 in Charleville, Enniskerry, County Wicklow, Ireland). Lady Monck was the first viceregal consort of the Dominion of Canada and the first to live at Rideau Hall.

Early Life and Family

Elizabeth Monck was the fourth of 11 daughters of Anglo-Irish aristocrats Henry Stanley Monck, 1st Earl of Rathdowne and 2nd Viscount Monck, and Lady Frances Trench, daughter of William Trench, 1st Earl of Clancarty. Elizabeth and her sisters were heiresses to their father’s fortune, but they could not inherit his titles. The earldom became extinct on their father’s death, and the title of Viscount Monck passed to their uncle (and Elizabeth’s future father-in-law), Charles Monck. Elizabeth’s great-granddaughter Elisabeth Batt wrote that, “As a girl, Elizabeth had been considered rather too daring by some of her sisters; hardy and active.”

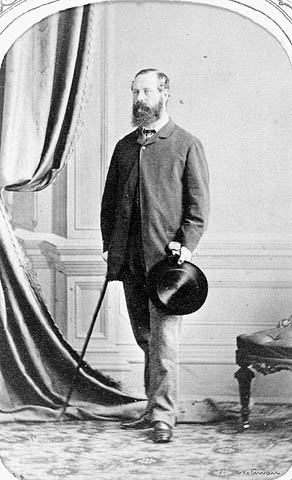

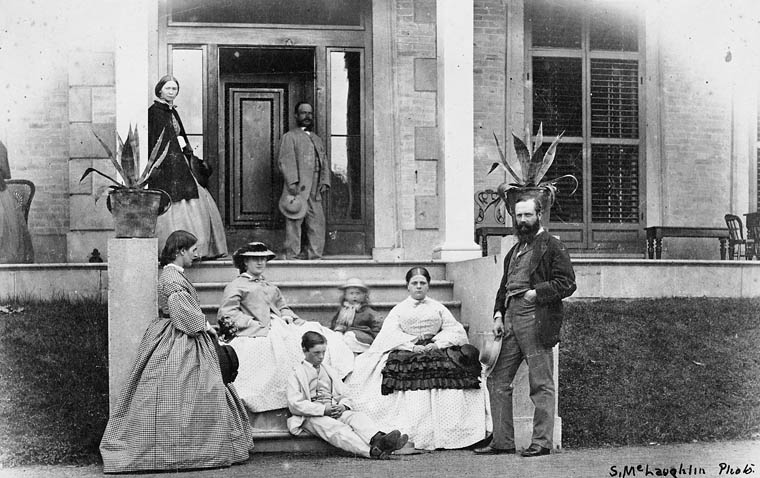

On 22 July 1844, Elizabeth married Charles Stanley Monck, her first cousin, who succeeded his father as the 4th Viscount Monck in 1849. They had seven children. Four survived to adulthood: Frances, Henry, Elizabeth and Richard. The Moncks were a close family, and all four children accompanied their parents to Canada.

Frances became deaf as a result of scarlet fever at the age of three. Prior to becoming viceregal consort, Lady Monck spent part of each year in Paris with her daughter so that she could attend the School for the Deaf (now the National Institute for Deaf Children of Paris). The school was a model for deaf education in the United Kingdom and North America.

Viceregal Consort of Canada

Viscount Monck was appointed governor of British North America in 1861. He arrived in Quebec City with his family in October of that year. Lady Elizabeth Monck’s early months in Canada were difficult. She was homesick for Ireland. There was no suitable residence upon their arrival, and the Moncks lived in cramped temporary accommodations at Parliament House and, later, on Rue St. Louis. They eventually moved to Spencer Wood, outside the city, once it was restored after a fire. Lady Monck enjoyed French Canadian society and visited the Ursuline convent and Laval University. This prompted criticism in English Canadian newspapers that the Moncks were open to “undue Papal and French influence.”

Lady Monck made public engagements in Canada West (Ontario) and Canada East (Quebec), where she visited schools and orphanages and invited children to visit Spencer Wood. She did not travel outside those provinces, though, as transportation options were limited. Future viceregal tours would involve the Intercolonial and Canadian Pacific Railways, which were constructed later in the 19th century.

In 1864, Lady Monck and her children returned to Europe to manage the family’s Irish estates and present Frances to Queen Victoria. Therefore, Lady Monck did not attend the Quebec Conference hosted by Viscount Monck in October 1864. Her niece, Frances “Feo” Monck, acted as hostess in her place. Lady Monck returned to Canada and hosted a soirée to celebrate the opening of the Dominion of Canada’s first parliament later that year. Like her husband, Lady Monck was critical of the choice of Ottawa as Canada’s new capital, but she devoted considerable attention to the landscape and gardens at Rideau Hall.

Political Contacts

Lady Elizabeth Monck was interested in Canadian politics and corresponded with prominent Canadian politicians, including Hector-Louis Langevin, George-Étienne Cartier and Thomas D’Arcy McGee. McGee called Lady Monck “my Governess General” and described her as “one of my best friends.” Lady Monck’s attitude toward Prime Minister John A. Macdonald was more critical, as she disapproved of his excessive drinking at her receptions.

Lady Monck continued to follow Canadian politics during her time in Europe. For example, in March 1865 she wrote to her son Henry, who was then attending Eton College in England: “The federation plan has passed in the Canadian parliament with large majority…There are great fears that it will be thrown out in New Brunswick, owing to the results of the elections.” Lady Monck kept a journal during her time as viceregal consort, but it was lost. (See also Mothers of Confederation.)

Reputation

Lady Elizabeth Monck had a reputation for formality. In 1903, a book about prominent Canadian women by Henry J. Morgan stated that “Her ladyship became very unpopular with the ladies of Canada, in consequence of her exacting methods touching court dress, and for other reasons.” Later, Canadian history books emphasized her unpopularity compared to later 19th-century viceregal consorts, especially the sociable Lady Dufferin. According to Elisabeth Batt, Lady Monck criticized the informality of Canadian social occasions, but her friends and neighbours in Canada made “affectionate tributes to her warmheartedness and spontaneity.”

Later Life

Lady Elizabeth Monck returned to Ireland with her husband at the end of his term as governor general in 1868. Since she suffered from poor health, Monck declined subsequent overseas appointments, such as the governorship of Madras, India, out of concern for the effect of the hot climate on her health. Lady Monck died in 1892, two years before her husband.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom