Margaret Tryphene Francis Crang, lawyer, politician, labour activist (born 30 August 1910 in Edmonton, Alberta; died 3 January 1991 in Vancouver, British Columbia). Margaret Crang was the youngest person ever to serve on the Edmonton City Council; in 1935, she became the first woman to be reelected. She briefly visited the front of the Spanish Civil War in 1936 and made headlines by firing a rifle for the Republican forces. Throughout her active career in politics and law, she was an advocate against fascism and for workers’, women’s and immigrants’ rights.

Family Background and Education

Margaret Crang was born in the Garneau neighbourhood of Strathcona, Alberta (part of the City of Edmonton since 1912). She was the fourth of six children of Dr. Francis (Frank) William Crang and Margaret Bowen. Frank Crang, who had grown up in Ontario and worked as a bricklayer as a young man, completed his high school education in his twenties and then studied medicine. After moving to Strathcona with his wife in 1903, he became the community’s first physician and served on the school board for 25 years. His work exposed Margaret to poverty and suffering in the community, while his openly socialist stance and the political gatherings he hosted at the family home influenced her toward social activism.

Crang attended Strathcona High School and studied at the University of Alberta. She was known as an outstanding student and received a Bachelor of Arts in 1930, a Bachelor of Law in 1932 and a teaching diploma in 1933. From 1930 on, she also held summer jobs in Edmonton law firms. After graduation, she completed her articles with the law firm Newell, Lindsay, Emery and Ford (Emery and Jamieson as of 1972). She was admitted to the bar in 1934.

Crang was an avid athlete during high school and university. She participated in track and field competitions and was a sprinting champion. After a knee injury, she switched to swimming, leading the University of Alberta swimming team as captain for three years.

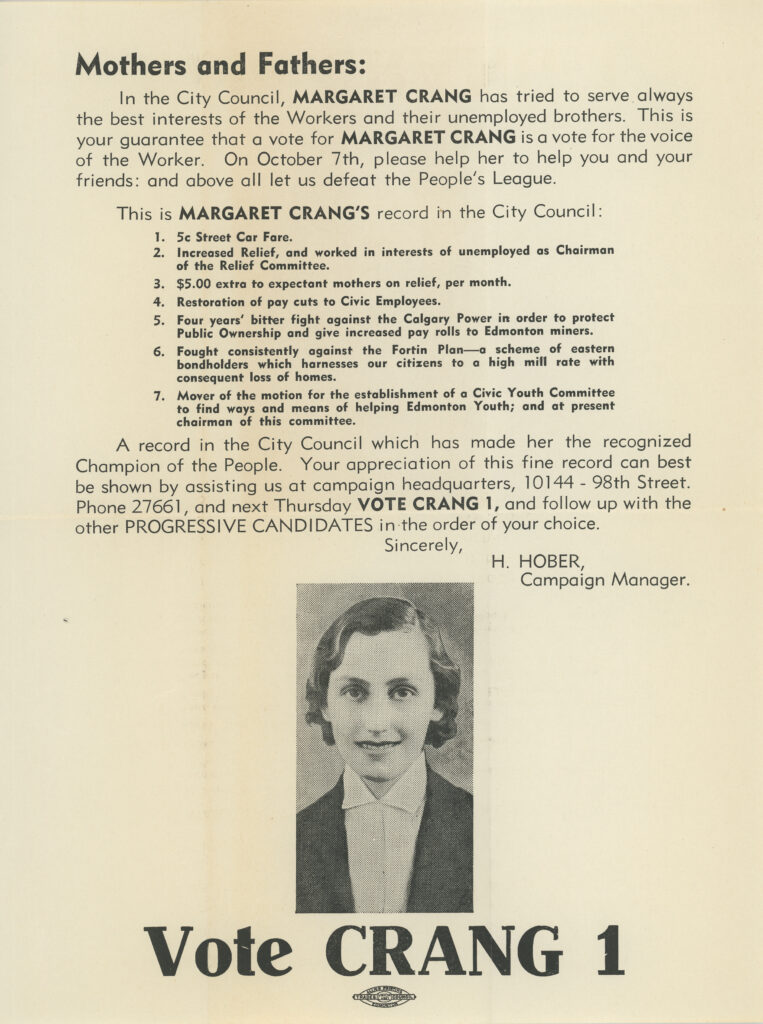

1933 Edmonton City Council Campaign

During the Great Depression, unemployment, hunger and homelessness were rampant in Edmonton; public relief was insufficient and often ineffective. Unmarried women and working mothers were at particular risk of poverty, but their concerns were largely ignored in the public debate. Margaret Crang decided to run for election to Edmonton City Council in November 1933. As the only female candidate, she used her gender as an asset in a campaign for targeted, effective relief: she said, “[I]f a woman could be given influence, so much more discretion could be used in attending to the wants of those in dire need” and “A woman can decide questions of better food and housing that come up in connection with relief better than a man.”

Crang ran on a Labour ticket but supported the newly founded Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), the predecessor of today’s NDP. She was already a skilled campaigner: she had gained experience in public speaking from her legal work, supported her father in an earlier school board reelection campaign and given election speeches for his friends. She also had a detailed platform, proposing a female relief officer, adequate medical aid for people on relief, adjustment of relief benefits to the general cost of living, public ownership of utilities and other social welfare policies.

In the election on November 8, Crang won her seat on the council with the second-highest number of votes. At a time in which women’s suffrage was still new and rather limited in other provinces, this gave her national prominence. Newspapers across Canada reported on the “girl alderman.”

First Term and Re-election

On the Edmonton City Council, Margaret Crang was an uncompromising advocate for workers and women, never shying away from confrontation. She joined the hiring committee for the Relief Department, which recruited two female relief officers, but she also fought the department whenever she found its policies insufficient. She became the chair of a Special Relief Committee that handled appeals when relief had been denied. She achieved raises in relief payments, threatening resignation from council if the proposed increases were not put into action. She also traveled across the country to observe other cities’ and municipalities’ relief policies and collect ideas. Her struggle for workers’ rights explicitly included Chinese and other immigrant workers, which was unusual for the time. Her efforts in this regard, however, were unsuccessful; under the immigration legislation of the Great Depression, relief was not available to unemployed immigrants, who faced deportation.

While serving on the council, Crang continued to pursue her legal career. After being admitted to the bar in 1934, she started her own law practice and took on labour cases, many of them pro bono. In addition, beyond her council duties, she campaigned for workers’ rights and for peace. She gave talks on topics like the benefits of a socialist welfare system or the need for a global alliance of workers; and she represented Alberta in the Canadian League Against War and Fascism (CLAWF), a nationwide organization allied with the Communist Party.

On 13 November 1935, Crang was reelected to the Edmonton City Council with the highest number of votes. No other woman would achieve this until 1964.

1936: At the Front of the Spanish Civil War

In September 1936, during her second term as city councillor, Margaret Crang traveled to Brussels as CLAWF delegate to the Universal Peace Conference. One of the pertinent issues was the recently erupted Spanish Civil War. Crang viewed Spain, where Republican (left-wing) government forces were fighting a fascist-backed Nationalist insurgence, as “the battleground of democracy.” She predicted (correctly) that a Nationalist win would lead to a world war and thought of Canada’s neutrality in the conflict as “crazy.”

After the peace conference, Crang traveled to Spain with nine other delegates to obtain first-hand information. They were permitted to the front as honorary members of the Republican militia and went to Barcelona, Madrid, Toledo and Valencia. In a series of articles Crang wrote for the Edmonton Journal, she stressed the presence and courage of female fighters among the government militia. In an apparently impulsive act of solidarity during one of her front visits, she shot two bullets from a rifle “for the government side,” as she later told the Edmonton Journal. Although the shots were not directed at anyone, the incident caused nationwide controversy: Editorials across Canada criticized Crang’s use of the gun as contradicting her self-proclaimed pacifism and “unwomanly” or “foolish.”

1936–43: Political, Social and Legal Activism

After her return to Canada in October 1936, Margaret Crang became an advocate for the Spanish cause, touring the country for promotion and fundraising. In the summer of 1937, she met Dr. Norman Bethune, a Canadian Communist who supported the Republican troops in Spain, and accompanied him on a speaking tour of southern Alberta.

In council, Crang continued to fight for fair salaries and children’s and youth welfare. However, after her second term on the Edmonton City Council, her political career quickly declined. She lost her seat on the council in the November 1937 election and was unable to win it back in two subsequent campaigns. She also ran unsuccessfully for a seat in Alberta’s provincial parliament three times. This was related to a general decline of support for left-wing politics in Alberta, which had two main reasons: a fragmented party landscape on the political left (parties included the Liberals, Labour, the Communist Party, United Farmers of Alberta and the new CCF, each with its own ideology and voter groups) and the rise of the conservative Social Credit movement. In Crang’s specific case, she did not commit to any one political party; driven by the hope to reunify the political left, she first ran for Labour, later as an Independent or for yet another new party, the Civic Progressive Association. This lack of party loyalty alienated many of her voters and former collaborators. She also showed increasing support for Social Credit, further damaging her political popularity. The negative publicity surrounding her visit to Spain may have played a part as well.

From 1938 to the early 1940s, Crang focused on her law practice and community activism. She represented victims of relief cuts or domestic abuse, as well as members of ethnic and religious minorities. In December 1938, she convinced the Edmonton Hospital Board (on which she served) to accept the city’s first Black nursing student. She also became involved with the Empire Opera and supported gay members of the theatre community under persecution from the RCMP.

Later Life, Illness and Death

With her political career over, Margaret Crang moved to Montreal in 1943 and became a writer for the Montreal Gazette. However, it is unclear how long she was able to work in this position, as she was diagnosed with Cushing’s syndrome in her thirties. Crang went to Boston, where she underwent removal of both adrenal glands (an experimental treatment at the time); she then lived with her sister in Edmonton to recover, having lost much of her vitality and energy.

In 1953, Crang relocated to Vancouver, where she spent the last decades of her life. She no longer participated in political life or activism but remained interested in political topics and grew marijuana. Her death on 3 January 1991 went largely unnoticed.

Legacy

Independent, hard-working and unafraid of confrontation, Margaret Crang was a champion for equal rights and social justice long before the civil rights movements of the 1960s and 70s. (See Rights Revolution in Canada.) Her inclusive approach to labour rights was ahead of her time. She advocated not only for employed men but also for the unemployed, for married and unmarried women with jobs and childcare needs and for ethnic groups discriminated against by the law. This set her apart from the ideology-driven, competing progressive parties of the Depression years. On the international stage, she threw herself into the struggle for peace with the same passion, foreseeing the dangers of fascism with almost visionary precision.

One of the first women to gain widespread support in an election campaign, Crang was a trailblazer for women’s political representation. On the night of her first election to the Edmonton City Council, she said, “[I]f I have led the way for other women to take active part in civic affairs, I have accomplished one of my objects.”

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom