Ruth Lor Malloy (née Lor), journalist, writer, activist (born 4 August 1932, in Brockville, ON). Malloy was a key figure in fighting against discrimination in Ontario in the 1950s (see Prejudice and Discrimination in Canada). She participated in the high profile Dresden restaurant sit-in of 1954. In 1973, she published the first English-language guidebook to China in North America. Throughout her decades-long career, Malloy worked tirelessly to foster intercultural dialogue and justice for marginalized groups.

Early Life

Ruth Lor Malloy was born in Brockville to a Chinese-Canadian family who owned a restaurant. Malloy’s mother was born in Canada while her father emigrated from China to Canada at 12 years of age (see also Immigration to Canada). Malloy spoke Chinese with her family until she was 5 years old, but she lost her ability to speak the language fluently after starting school due to wanting to assimilate with her peers. During her childhood, she experienced racial discrimination (see also Anti-Asian Racism in Canada). In grade school, strangers would call her names in the street. As a teenager, she was excluded from the social circles of her peers. In a 2022 interview with Diamond Yao, Malloy explained that these experiences left her devastated.

Malloy enjoyed geography classes in high school. This interest led her to pursue a career in journalism. At the time, it was a difficult career choice, with few Chinese-Canadian journalists employed in mainstream media. Many professions at the time, such as pharmacy, law, teaching and politics, were also restricted to Chinese-Canadians due to their citizenship requirement. These requirements barred individuals who were not British subjects by birth or naturalization from pursuing certain professions (see British Subject Status). By 1947, the Canadian Citizenship Act was legislated, which allowed for persons born in Canada and for naturalized immigrants to become Canadian citizens and not British subjects. Canadians of Chinese descent were able to attain Canadian citizenship status in 1947 (see Canadian Citizenship; Chinese Immigration Act).

Malloy’s family attended a local Presbyterian church in Brockville (see also Presbyterian and Reformed Churches in Canada). During the Second Sino-Japanese War, local Brockville leaders gave her and her siblings important roles in raising money for China war relief efforts. She credits this experience for giving her the confidence to fight back against racial discrimination (see also Racism; Prejudice and Discrimination in Canada).

Education and Early Activism

In the 1950s, Malloy attended Victoria College at the University of Toronto. She was able to pursue higher education in part because she won a car in a lottery. The car was sold with proceeds being distributed between her family. Malloy’s share went towards her college fund. An uncle in Toronto was also willing to host her for the duration of her studies.

Malloy became more politically active at university. While still a student, she was involved in organizing a delegation to Ottawa to petition the federal government to change Canada’s immigration policy, which restricted Chinese immigration to Canada. Under Order-in-Council, P.C. 2115, only the spouses and unmarried children (under the age of 18) of Canadians citizens of Chinese descent could immigrate to Canada (see Chinese Immigration Act; Immigration Policy in Canada). Malloy organized a delegation to petition the federal government to include grandparents as a category of family members that could immigrate. The delegation went to Ottawa in 1958 to petition Minister of Immigration Ellen Fairclough. The law was successfully changed in 1967.

Malloy was also involved with the Student Christian Movement of her university. As a member of that organization, she joined in efforts to fight apartheid in South Africa and to promote intercultural dialogue between Canadian and Chinese people. Malloy graduated with a general BA with a focus on sociology and philosophy in 1954.

The summer after her graduation, Malloy signed up for a month-long workshop on nonviolent ways to fight racial discrimination in Washington, D.C. The workshop was led by Black civil rights activist Wally Nelson. During the workshop, she was part of a multiracial group that tested whether soda fountains would serve Black people and visited segregated swimming pools.

Restaurant Sit-Ins in Dresden

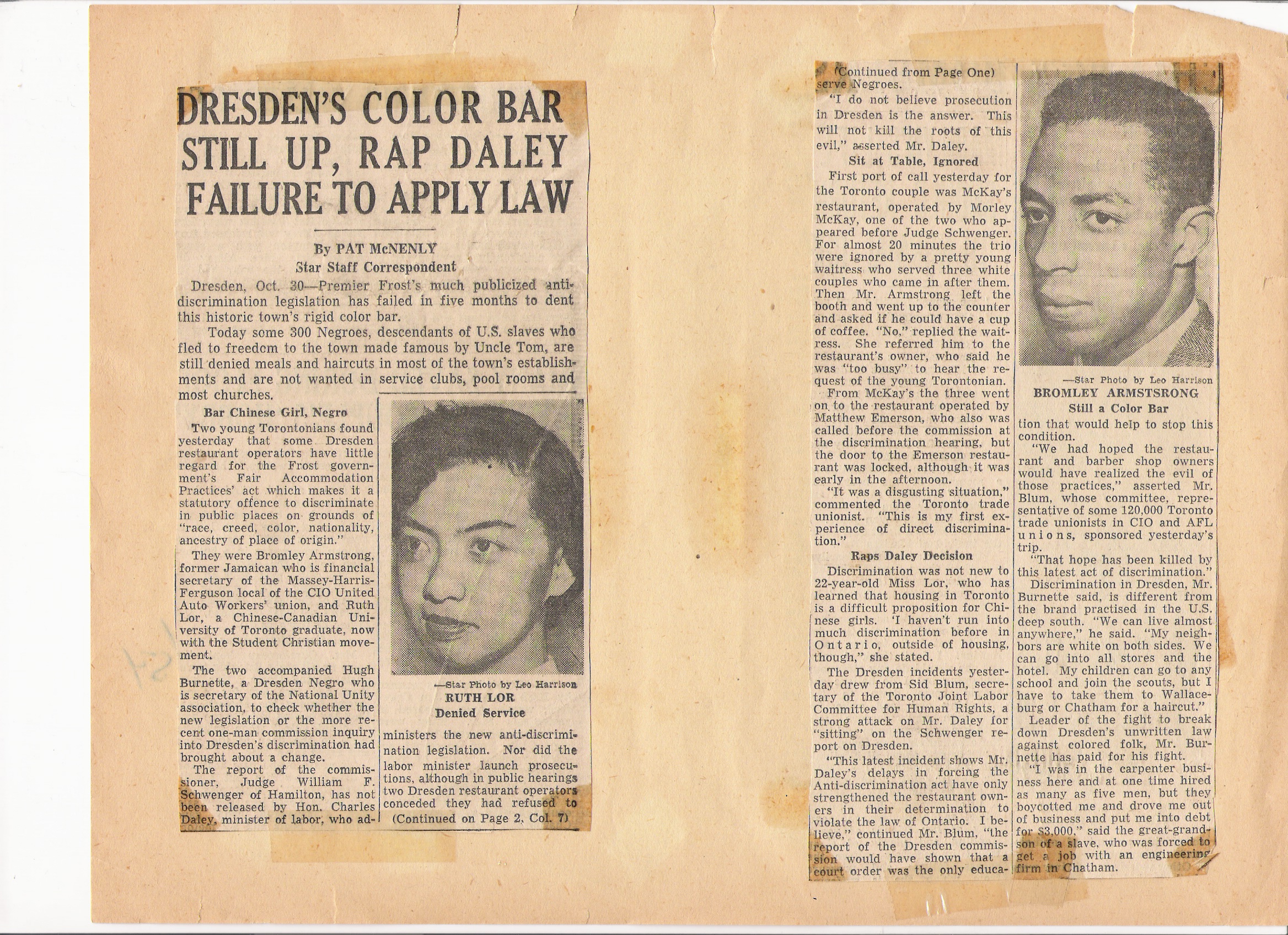

Upon returning to Toronto, Malloy was introduced to Sid Blum, the secretary of the Toronto Joint Labour Committee for Human Rights. At the time, Blum wanted to evaluate whether public accommodations in Dresden, Ontario, were complying with the 1954 Fair Accommodation Practices Act. The newly passed law forbade discrimination in public service and housing on the basis of gender, race, religion, and other identity criteria. However, Blum suspected that many businesses were still refusing to serve Black customers. (See also Racial Segregation of Black People in Canada.) He wanted to prove this discrimination with a “test.” He asked Malloy to participate in a “test” and she agreed. (See also Prejudice and Discrimination in Canada.)

Malloy worked alongside Black civil rights activists Hugh Burnett and Bromley Armstrong for this “test” at Kay’s Café, a restaurant in Dresden. The group invited lawyers and members of the Toronto media to participate. On the day of the test, the reporters, who were white, entered the restaurant and were served. Malloy, Burnett and Armstrong followed suit and sat at a separate table. However, the waitress who served the group of reporters ignored them. After approximately 15 minutes had passed with no offer of assistance, Armstrong asked for a coffee and was refused service. Burnett asked for the manager, Morley McKay. McKay came out of the kitchen wielding a cleaver, in an attempt to intimidate the group. When he retreated, Burnett returned to the table and the reporters started taking pictures of the group.

The next day, the story made headlines in Toronto newspapers. McKay was charged with breaking the law and was tried at the Chatham Ontario Court. Although McKay was initially found guilty, the case was overturned on appeal because the judge ruled that there was no clear evidence of racial discrimination and that service had only been postponed, rather than refused. Malloy and her group worked on another test case that proved the act was valid. McKay was subsequently fined for breaking the law. From then on, Dresden businesses served everybody regardless of race, according to Malloy during her 2022 interview with Diamond Yao.

Journalism and Writing Career

Malloy started her journalism career during a stay at a Quaker work camp in Mexico. She had received a scholarship to cover the expenses of her trip. Sandy Runciman, an editor of Brockville Recorder & Times, offered to pay her $5 for each article she would write about her experiences there.

In 1963, after a chance encounter in her lobby, Malloy was invited to a dinner party thrown by the Canadian Minister of Agriculture, Harry William Hays. At the event, she met some Chinese journalists who helped her get a visa to visit China as a freelance journalist. It was extremely rare for Canadian citizens to be granted the document at the time. During her stay in China, Malloy met her Chinese relatives for the first time and visited several cities. She made a second trip in 1973 with her 5-year-old daughter to find out what happened to her relatives during the Cultural Revolution. During her travels, she met several Americans of Chinese descent who, like her, could not speak any Chinese dialects and who struggled to navigate the country. Malloy used these experiences to write what was likely the first English-language guidebook on China for diasporic Chinese people, titled A Guide to the People's Republic of China for Travelers of Chinese Ancestry (1973). Her uncle designed the cover. The first print run of 800 copies was published in 1973 and was sold mostly to Chinese Americans. Its success led her to write almost a dozen English-language guidebooks on China. Malloy’s last guidebook was published in 1980.

In 1997, Malloy also published the book Hijras: Who We Are, in collaboration with Meena Balaji. Malloy spent time in India interviewing Balaji, who is hijra, and collaborating with a group of Hindus and Jains. Through this inter-faith effort, Malloy hoped to raise awareness about the systemic discrimination hijra people face in India.

Throughout her career, Malloy would participate and write about her experiences in several work camps in Brazil, the Canadian Arctic, and Japan. Her work focuses on themes of intercultural dialogue and justice for marginalized populations.

From 2010 to 2020, Malloy ran the blog Toronto Multicultural Calendar. She wrote about various events happening in the different cultural communities of the city. Her aim was to foster cultural exchanges within the city of Toronto.

In 2023, Malloy published her memoir Brightening My Corner: A Memoir of Dreams Fulfilled with Barclay Press.

Personal Life

In 1963 Malloy met her husband, American journalist Michael Malloy, while they both were working in India. They married in Hong Kong in 1965 and had three children together. Since 1984, the family has resided in Toronto. Michael Malloy passed away on 14 August 2021 after a long battle with cancer.

In addition to her first bachelor’s degree, Malloy holds a second bachelor’s degree in social work from the University of Toronto. She graduated in 1960.

Raised Presbyterian, Malloy became a lifelong Quaker after her experience at a Quaker Mexican work camp.

After the restaurant sit-ins, Malloy and Bromley Armstrong became lifelong friends. In 2013, she attended the ceremony where he received an honorary Doctor of Laws degree from York University. Together, they also filmed accounts of their respective work for the CBC and the National Film Board of Canada’s documentary Journey to Justice by Roger McTair.

Honours and Awards

- Honorary Doctor of Laws, York University (2023)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom