Indigenous History

Archeologists estimate that people have occupied the Forks for at least 6,000 years. A series of archeological digs conducted between 1989 and 1994 unearthed an ancient hearth, indicating that bison hunters were at the site around 4,000 BCE.

The Forks and the city of Winnipeg are on the traditional territory of the Cree, Ojibwe, Oji-Cree, Assiniboine and Dakota. The oral history of the Cree asserts that the name Winnipeg means “muddy waters” because of the murky look to the water where the Red and Assiniboine rivers meet. The Forks is also known as the birthplace of the Métis Nation (see also: Métis; Métis National Council).

Elders say the site has been a part of Indigenous history for generations. It’s where many nations met to engage in trade, traditional healing, politics and even battle. As a meeting place, no single nation had an exclusive right to the Forks, which saw much trade and celebration over the centuries, as well as many clashes between Indigenous nations. The Forks also served as a military centre for various nations. According to Clarence Nepinak of the Pine Creek First Nation, the river was called Miskosipi — “Red River” — because “so many people died at one of these battles, the river flowed red.”

Fur Trade

The first two Europeans to reach the Forks were employees of French fur trader and explorer Pierre Gaultier de Varennes et de La Vérendrye. They arrived in 1734. Four years later, La Vérendrye commissioned the construction of Fort Rouge at the river juncture. Fort Rouge soon fell out of use and would later be replaced by other forts and trading posts. Until his death in 1749, La Vérendrye developed the fur trade in the Prairies and, along with his youngest son, Louis-Joseph, led a search for an overland route to the Pacific Ocean.

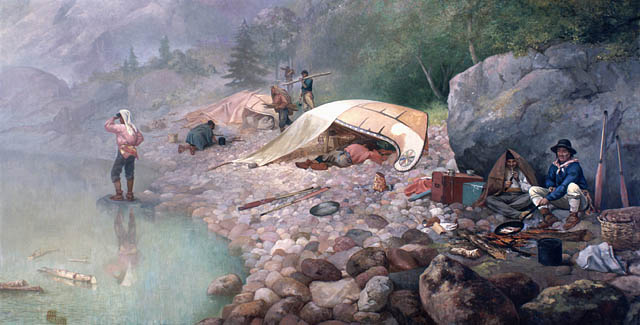

Fur trading slowed as the French diverted their resources to fight the Seven Years’ War (1756–63) against Britain. In the latter half of the 18th century, however, voyageurs resumed their business in the West, with Montreal-based merchants controlling most of the trade. This period also saw the migration of Métis from the northern Great Lakes region to the area around the Forks, where many supplied pemmican for the North West Company (NWC).

Site of Conflict Between the HBC and NWC

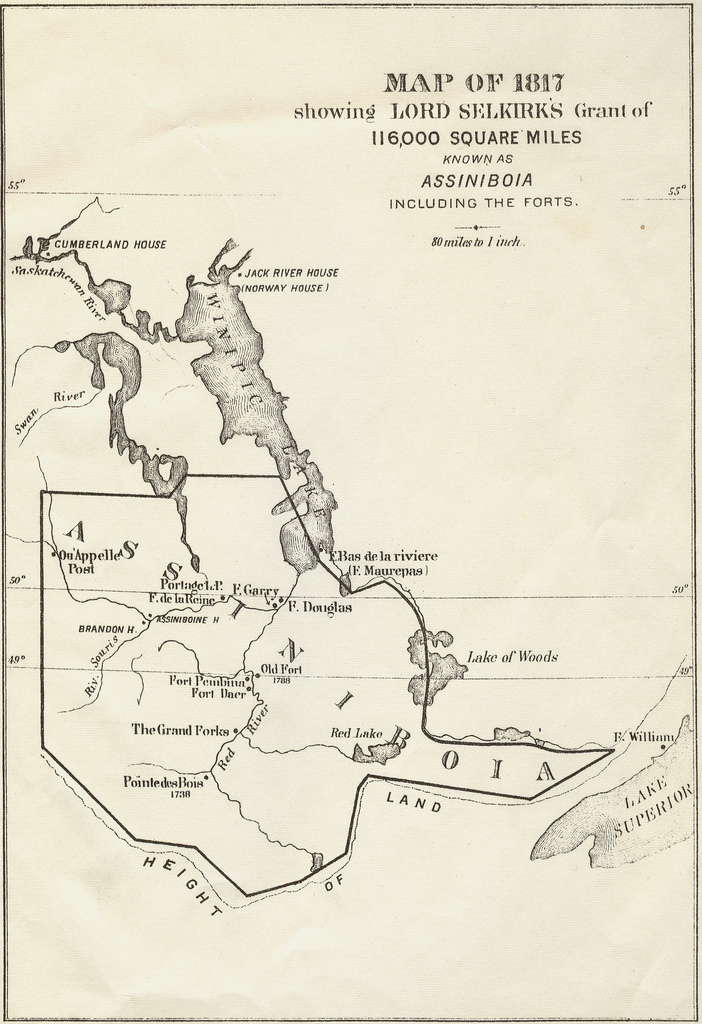

The NWC was a partnership of nine fur-trading operations that defied the exclusive charter King Charles II had, in 1670, granted the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) over Rupert’s Land, which included the Forks. In the 1770s, the HBC began to expand its business inland from Hudson Bay. This resulted in a decades-long rivalry between the HBC and the NWC. In 1811, the HBC granted Thomas Douglas, Earl of Selkirk, an area of 116,000 square miles (300,439 km2) along the Red and Assiniboine rivers, where he founded a settlement of Scottish and Irish immigrants known as the Red River Colony, or Assiniboia.

The Forks was included in this land grant. It was also, by this time, the site of the NWC’s Fort Gibraltar, built c. 1806–10 to replace temporary trading encampments. Not far downriver, the Red River Colony erected its own headquarters, Fort Douglas, by 1815. With the NWC and the HBC vying for control of the lucrative fur trade in such proximity, violent conflicts erupted between the Nor’Westers, who were largely French Canadian and Métis, and the newcomer Scots and Irish of the HBC. Tensions peaked in 1816 with the destruction of Fort Gibraltar by the Red River Colony and the ensuing Battle of Seven Oaks on 19 June.

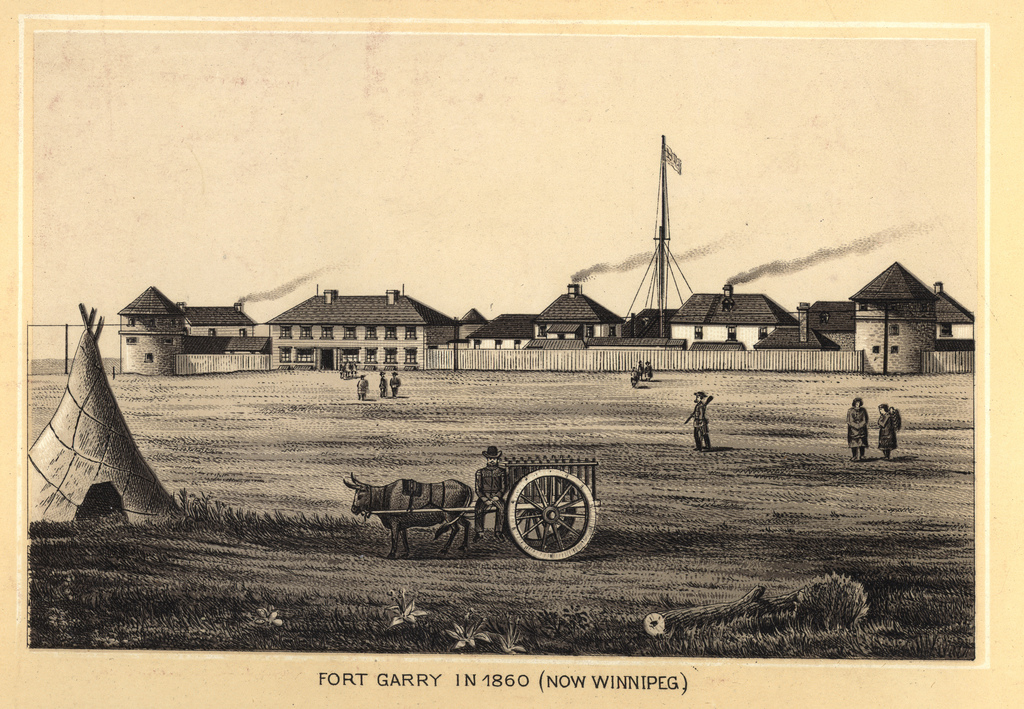

In 1821, with the NWC struggling to remain profitable and the British government pressuring both parties to reach a peaceful resolution, the Hudson’s Bay Company and the North West Company merged under the HBC banner (see The North West Company: 1779–1821). Fort Gibraltar was renamed Fort Garry the next year, but was damaged by flooding in 1826, prompting the HBC to build Lower Fort Garry approximately 30 km north on the Red River. In 1835, the HBC rebuilt its fort at the Forks as Upper Fort Garry; the next year, it officially assumed administration of the Red River Colony.

After the merger, many Métis traders settled in the colony, which grew as a distinct multicultural society into the mid-1800s. The Métis powerfully lobbied the HBC on issues related to trade and government in the Red River Settlement.

Red River Rebellion

In 1869, the HBC agreed to transfer Rupert’s Land to Canada, which had been created two years before with the Confederation of British North American colonies in the East. The Red River Métis were not consulted on the transfer, and, faced with the encroachment of anglophone Protestant settlers from Ontario, many feared that their religious, cultural and land rights would be ignored by the new government.

Led by Louis Riel, the Métis staged a rebellion and formed a provisional government in an attempt to force Canada to the negotiation table. The rebels captured Upper Fort Garry at the Forks in November 1869, where they imprisoned several settlers from Ontario who opposed the rebellion. They court-martialled and executed one of these prisoners, Thomas Scott, by firing squad in the fort’s courtyard in March 1870. Canada finally negotiated with the Red River Métis, and the province of Manitoba was created with the Manitoba Act of 1870.

Immigration and Railway Hub

The city of Winnipeg, incorporated in 1873, became a hub for travelling immigrants and a gateway to the West. In 1872–73, two “immigration sheds” were built at the Forks to process settlers arriving by riverboat from the United States. These buildings accommodated several hundred immigrants at a time. Under their roofs, newcomers received land grants before continuing to their destinations.

In the late 1800s, the Canadian government actively promoted immigration to Western Canada ( see History of Settlement in the Canadian Prairies). Starting in 1886, the Forks saw an intense period of railway development that effectively carved the Forks off and penned it into a small area along the riverbanks. Stations and rail yards were built to accommodate four railways: the Northern Pacific and Manitoba Railway Company, Canadian National Railway, Canadian Northern Railway and Grand Trunk Pacific Railway. The latter two companies partnered with the National Transcontinental Railway and the federal government to build Winnipeg’s Union Station, completed in 1911 on land adjacent to the Forks and still in use today.

Historic Sites

In 1974, the federal government designated public land on the north and south banks of the Assiniboine River and the west bank of the Red River as The Forks National Historic Site. The Forks is home to several additional historic sites, including Forts Rouge, Garry and Gibraltar National Historic Site of Canada, which commemorates the various fur-trading posts that stood at the river juncture. While archeologists have found evidence of the earlier forts, remnants of Upper Fort Garry are the only ones visible on the present landscape.

Tourist Destination

The Forks emerged as a tourist destination in the late 1980s. A community development corporation, The Forks North Portage Partnership, has been influential in shaping this relatively recent identity. Formed from the merger of two corporations founded in the 1980s to redevelop the district, the partnership promotes the Forks’ role as a mixed-use meeting place.

Buildings from the railway era have been preserved and repurposed. The Forks Market, for example, occupies the former horse stables of the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway and the Great Northern Railway. Johnston Terminal, once a railway warehouse, now houses shops, offices and hospitality services. The Manitoba Children’s Museum occupies a former train repair shop built in 1889.

Meeting Place

The Forks is now often referred to as part of Treaty One Territory, in reference to the 1871 agreement between the Crown and First Nations (see Treaties 1 and 2). The area has remained true to its history of being a location for important dialogue and correspondence, despite the development it has seen over the past two centuries.

Today, the Forks is common ground for Indigenous people, Winnipeggers, Manitobans, Canadians, newcomers and tourists from around the world. The Scotiabank Stage, an outdoor amphitheatre, hosts many events throughout the summer months, including the annual Pride Winnipeg Festival and the Aboriginal Peoples Television Network (APTN)’s annual Aboriginal Day Live. At the Forks’ centre is Oodena Celebration Circle, an outdoor amphitheatre where many sacred events happen throughout the year. It’s where the annual Manito Ahbee Festival kicks off and where powwows are held during the summer months. The Forks also hosts guided tours (in July), as well as tipi teachings for schools and the public that incorporate traditional activities such as bannock making and storytelling. Officials currently overseeing the Forks have promised to maintain a relationship with knowledge keepers to continue supporting the transfer of historical knowledge to future generations from all walks of life.

Monuments and Museums

Monuments at the Forks commemorate various aspects of the area’s history. Built in 1990–91, the Wall Through Time illustrates the story of the Forks with plaques mounted on a curving brick wall. The structure skirts an important archeological site near the Assiniboine River — a 3,000-year-old Indigenous campsite and trade centre. The Path of Time (1991), a sculpture by Marcel Gosselin, features a bronze shell around a piece of smooth limestone. From the shell have been cut outlines of tools that people have used to shape the history of the Prairies. As the sun moves across the sculpture, it casts the images of the tools onto the limestone.

A monument honouring the lives of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls was unveiled at the Forks on 12 August 2014. Several days later, roughly one kilometre north, the body of 15-year-old Tina Fontaine was pulled from the Red River. The death of the teen from the Sagkeeng First Nation opened the eyes of many Canadians to the issue of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls and prompted renewed calls for a national inquiry into the crisis. On the evening of 19 August 2014, hundreds of people gathered at a vigil for Fontaine at Oodena Circle.

The Forks is also home to three museums. The Winnipeg Railway Museum, located in Union Station, features antique railway cars, equipment and exhibits related to the city’s railway history. The Manitoba Children’s Museum contains 12 permanent galleries as well as temporary travelling exhibitions, all designed to engage children in activities that promote learning, creativity and growth. The Canadian Museum for Human Rights opened its doors in 2014. Spokespersons say it has been built to serve as a beacon of positive change and reconciliation in Canadian society. It is where residential school survivors came to meet and share as part of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s initial meetings in 2009.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom