In 1959, an article in the Journal of Negro History announced the discovery of copies of a weekly newspaper long believed lost to history. A sizeable print run of a dust-covered bound volume of The Provincial Freeman, which was published from 1853 to 1860, had been sitting in the library tower at the University of Pennsylvania since the early 1900s. What made this newspaper unique was not just that it was the second paper run by and for African Canadians. It made history as the first newspaper in North America to be published and edited by a Black woman, Mary Ann Shadd.

Foundation

Outspoken abolitionist and teacher Mary Ann Shadd moved to Canada in the fall of 1851 to set up a school for formerly enslaved children in Windsor, Canada West (present-day Ontario). However, she soon had a public disagreement with her sponsors, Henry and Mary Bibb and their allies, and the funding for her school was withdrawn.

After her school closed, Shadd soon hatched an ambitious new project. She launched a newspaper in which she could disseminate her views on her own terms. Not long thereafter, a first edition of The Provincial Freeman was published on 24 March 1853. (See also Newspapers in Canada: 1800s – 1900s.) The paper’s introduction stated that:

"The Provincial Freeman will be devoted to the elevation of the Colored People; and in seeking to effect this object, it will advocate the cause of TEMPERANCE, in the strictest and most radical acceptation of that term. Partly, because such are the well-known sentiments of its Editor, and, partly, because there is no such thing as the elevation of any people without it. For like reasons, the Freeman must be a straightforward, out outspoken ANTI-SLAVERY PAPER." – The Provincial Freeman (24 March 1853)

Initially, Shadd asked Samuel Ringgold Ward to lend his name and expertise as editor. Ward was a Congregational minister and respected agent of the Anti-Slavery Society of Canada. In addition, he had previously operated his own newspaper, the Impartial Citizen (1849–51), out of Boston and Syracuse, giving Ward critical experience in running a newspaper. Reverend Alexander McArthur, a white minister and Shadd’s friend and ally in Windsor, was named corresponding editor. Although the paper was clearly Shadd’s initiative, she was aware that her name on the masthead could alienate a readership that preferred the strict gender codes of 19th-century society. Ironically, Ward left for England 25 days later, and McArthur had long since left Windsor, having had little or no real involvement with the paper. Shadd then took to the lecture circuit to generate interest and subscriptions for the paper. One year later, on 25 March 1854, The Provincial Freeman began publishing weekly from No. 5, City Buildings, King Street East in Toronto.

Content

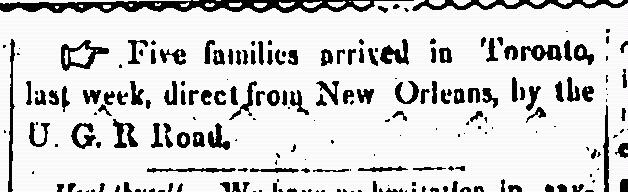

The Provincial Freeman was an anti-slavery newspaper, but as a leading emigrationist, Mary Ann Shadd strongly advocated Canada West as a place to settle for African Americans (see Emigration). The paper attacked racism, even within the abolitionist movement itself, and criticized the practice of “begging,” a form of fundraising in which agents travelled from town to town collecting money for the “poor, destitute, starving fugitives” whose condition was either grossly exaggerated or patently untrue. (See also Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.) Shadd also engaged in investigative reporting and muckraking (a form of exposé journalism), and she was not afraid to attack venerable institutions such as the Black church, Black and white leaders, or anybody else she believed was engaged in wrongdoing.

The paper’s motto was “Self-reliance is the true road to independence.” The importance of Black self-reliance and integration into Canadian society was another key component of The Provincial Freeman’s philosophy. Black people were advised to insist on fair treatment, and to take legal action if all else failed. The Provincial Freeman continually stressed that the de jure (legal) equality that Blacks enjoyed in Canada was one of the most significant aspects of life on British soil and that it needed to be taken full advantage of (see Black Canadians).

The newspaper also implicitly championed women’s rights, documenting the lectures of prominent American activists like feminist Lucy Stone and abolitionist Lucretia Mott. (See also Women’s Movements in Canada.) Moreover, it provided a forum for Black women, showcasing their talent and accomplishments. The paper sang the praises of such African American women as opera singer Eliza T. Greenfield and poet and orator Frances Ellen Watkins (later Harper). It also printed letters to the editor authored by Canadian Black women and gave public recognition to their literary and benevolent activities.

Later Years (1855–57)

In 1855, The Provincial Freeman moved to Chatham, as there was a large Black population there and in the surrounding area. Some of the leading Black leaders of the day were involved as editors or contributors to the paper. Baptist minister William P. Newman, and Ohio activist H. Ford Douglas, now in Chatham, acted as editors at one time or another. Other well-known abolitionists who had moved to Chatham and vicinity, such as William H. Day and Dr. Martin Delany, made valuable contributions. Mary Ann Shadd’s brother, Isaac, took over the role of publishing agent and was later elevated to editor alongside Shadd herself. Sister, Amelia, who had filled in as acting editor for a period, contributed articles, as did Shadd’s sister-in-law Amelia Freeman Shadd. Mary Ann Shadd often went on speaking tours in Canada and the United States to sell subscriptions for the newspaper and to advocate for the cause of anti-slavery and Canadian emigration. However, she remained the guiding force behind the paper throughout its tenure.

Closure

After a valiant effort to keep it going, the newspaper finally succumbed to financial pressures by the year 1860. However, seven years of publishing a newspaper under such circumstances was quite an achievement and, according to biographer Jane Rhodes, places it among a very small group of influential Black publications, including those of Frederick Douglass, a well-known African American abolitionist.

Legacy

The Provincial Freeman articulated the views and experiences of Black Canadians and showcased their successes. It furthered the Canadian cause to emigrationists, who often promoted Haiti, West Africa and other places (see Emigration). The newspaper also reported on the state of education in Canadian settlements. As a historical source, The Provincial Freeman has provided a treasure trove of information on the status of formerly enslaved African Americans who had escaped to Canada, the leading men and women in Canadian settlements, key organizations, important meetings and conventions, and the disputes and tensions within the various factions of the African Canadian community. Historian Jason Silverman has argued in Unwelcome Guests: Canada West's Response to American Fugitive Slaves, 1800–1865 (1985) that “The black press … engendered a sense of racial pride that was crucial to the well-being of the refugees in Canada West.” Perhaps this was The Provincial Freeman’s greatest achievement.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom