Athletic success, we’re told, takes grit and determination. With these strengths, an athlete can overcome any obstacle and, if they’re good enough, become the best in their sport, regardless of the challenges ahead of them. But what if the goalposts keep moving? What if the finish lines are drawn farther, the hurdles set higher, and the windows of opportunity sealed shut?

The athletes in this exhibit were not only the best in their fields, but among the best in history. They were the fastest sprinters, the most agile skaters, the hardest hitters and, in many cases, the first to succeed at a high level. But though they earned the respect of their elite peers and the awestruck admiration of onlookers, there were barriers to their success — a colour bar blocking their way.

Nevertheless, these courageous Black men and women persevered, and in so doing, cleared a path for future generations.

The Coloured Hockey League of the Maritimes (1895-1925)

The Coloured Hockey League of the Maritimes (CHL) was an all-Black men's hockey league founded in Halifax in 1895. Organized by Black Baptists and intellectuals, the league was designed as a way to attract young Black men to Sunday worship with the promise of a hockey game between rival churches following the service. Later, with the influence of the Black Nationalism Movement of the period — and with rising interest in the sport of hockey — the league came to be seen as a potential driving force for the equality of Black Canadians.

By the early 20th century, the CHL had expanded from a humble three-team league to include such regional clubs as the Truro Victorias, Amherst Royals and Hammond Plains Moss Backs. Between 1900 and 1905, games often out-drew those of white counterparts. The Inter-Provincial Maritime Championship between the CHL champion Africville Sea-Sides and the Charlottetown West End Rangers in Halifax drew 1,200 spectators.

Official league games were held between late January and early March, since teams were only permitted arena access after the white leagues’ seasons were finished. Games were played with no official rules other than the Bible, which ironically resulted in a more physical style of play and some key innovations, such as a goaltender dropping to his knees and an early form of the slapshot.

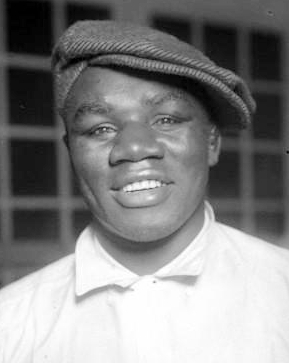

Sam Langford

Sam Langford was a professional boxer who competed across multiple weight classes during his 24-year career. A well-rounded boxer with fierce punching power, Langford often found success against much larger opponents and garnered praise as a fearless competitor.

Despite an impressive winning record and praise from icons of the sport, Langford, who was given the infamous nickname “Boston Tar Baby,” faced racial barriers throughout his career. Though he won heavyweight titles in England, Australia, Canada and Mexico, Langford is considered one of the best fighters never to win a title in the United States.

Some historians contend that Langford may have fought in over 600 bouts. At his peak, between 1906 and 1914, he won 85 of 87 fights. His professional record varies depending on the source — the most comprehensive listing is 214-46-44 with 138 knockouts.

Referred to as “the man the champions feared and would not fight, the man who was so good he was never given a chance to show how good he really was,” Sam Langford was inducted into Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame, the International Boxing Hall of Fame and the Nova Scotia Sports Hall of Fame. In 1999, he was named Nova Scotia’s top male athlete of the 20th century.

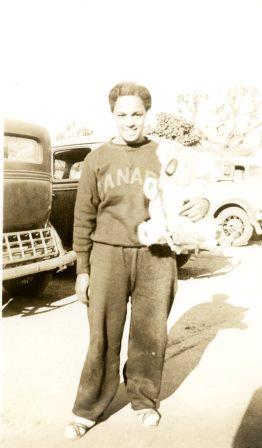

Barbara Howard

Barbara Howard is believed to be the first Black female athlete to represent Canada in international competition.

As a teenager at Vancouver’s Britannia High School, she established herself as one of the fastest sprinters in the city. In September 1937, when she was only 17 years old, she broke the British Empire record for the 100-yard dash with a time of 11.2 seconds, qualifying to represent Canada at the 1938 British Empire Games in Sydney, Australia. She was a media darling at the Games, where she finished sixth in the 100-yard race but won silver and bronze medals as part of the 440-yard and 660-yard relay teams. Howard never competed in the Olympic Games, which were cancelled in 1940 and 1944 because of the Second World War.

Determined to become a teacher, she attended Normal School and earned a Bachelor of Education degree from the University of British Columbia. In 1941, she became the first member of a visible minority to be hired by the Vancouver School Board.

Howard had a 43-year career in education, including 14 years as a physical education teacher, before retiring in 1984. She was inducted into the BC Sports Hall of Fame and Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame.

Herb Carnegie

Arguably the first Black Canadian hockey star, Herb Carnegie is widely regarded as the best Black player never to play in the National Hockey League.

Carnegie was considered small, but earned the nickname “Swivel Hips” for his ability to get past opposing players. A skilled skater and puckhandler, he was also a creative and instinctive playmaker. In 1938, Toronto Maple Leafs boss Conn Smythe allegedly remarked that he would take Carnegie “tomorrow” if he could “turn him white.”

After being relegated to the New York Rangers’ farm team, Carnegie chose instead to play in the Québec Provincial Hockey League (QPHL). In the 1947–48 season with the Sherbrooke Randies, he scored an astounding 48 goals and 79 assists in 56 games. With the Québec Aces in 1950–51, Carnegie played alongside Jean Béliveau, who called Carnegie “a super hockey player, a beautiful style, a beautiful skater, a great playmaker. In those days, the younger ones learned from the older ones. I learned from Herbie.”

In 1955, Carnegie founded the Future Aces Hockey School, the first registered hockey school in Canada. In 1987, he established the Future Aces Foundation, which has since provided more than $630,000 in scholarships.

Carnegie, who was also a champion senior golfer, was inducted into Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame and the Ontario Sports Hall of Fame. He received the Order of Ontario and the Order of Canada, among many other honours. The Investors Group, Carnegie’s employer for 32 years, instituted the Herbert H. Carnegie Award in 2003 for employees who demonstrate professional excellence and devotion to their community. The hockey arena formerly known as North York Centennial was changed to Herbert H. Carnegie Centennial Centre in 2005.

Harry Jerome

The first Canadian-born athlete to hold an official world track record, three-time Olympian Harry Jerome broke the Canadian record in the 220-yard dash when he was only 18 years old. He then set or equalled world records in the 60-yard indoor dash, the 100-yard dash, the 100 m sprint and the 440-yard relay.

After missing the 1963 racing season to recover from surgery to reattach his left quadriceps muscle — an injury so severe it almost ended his career — Jerome ran the 60-yard dash in six seconds in February 1964, equalling the world record. He won the bronze medal in the 100 m race at the 1964 Olympic Summer Games (the best performance by a Canadian in that event since Percy Williams won the gold medal in 1928), as well as gold medals at the 1966 Commonwealth Games and the 1967 Pan American Games.

Following his retirement, he promoted amateur and youth sport through national and provincial programs, and advocated for better support of Canadian athletes. He also petitioned the CRTC for better representation of minorities in broadcasting and lobbied Canada’s major department stores to use non-white models in their advertisements.

Jerome was inducted into Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame, the BC Sports Hall of Fame, the Canadian Amateur Athletic Hall of Fame and Canada’s Walk of Fame. He was made an Officer of the Order of Canada and named British Columbia’s Athlete of the Century. A statue of him was unveiled in Vancouver’s Stanley Park in 1988.

Angela James

The “Wayne Gretzky of women’s hockey,” Angela James was a pioneering and dominant force in women's hockey in the 1980s and 1990s, leading the Canadian team to four world championships (1990, 1992, 1994 and 1997). One of the first three women to be inducted into the International Ice Hockey Federation Hall of Fame, she was also one of the first two women, the first openly gay player and only the second Black athlete inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame.

James suffered racism and discrimination growing up, and was only allowed to play in a boys’ house league at age eight after her mother threatened legal action. James became the league’s top scorer but had to move into a girls’ program in Don Mills the following year when a new policy was passed restricting membership to boys. She started playing senior women’s hockey at age 13 and later led her Seneca College team to several championships. She was twice named athlete of the year in college.

A big, tough and talented goal-scorer, James drew comparisons to Mark Messier. After she was controversially omitted from Canada’s first women’s Olympic hockey team in 1998, James wrapped up her competitive career in 2000 scoring 44 points in 27 games in the National Women’s Hockey League.

A dedicated referee and championship-winning coach, James also established the Breakaway Adult Hockey School and was director of the Seneca College Women’s Hockey School. She was inducted into Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame and received the YWCA Women of Distinction Award for Sport. Her old rink in Toronto’s Flemingdon Park was renamed the Angela James Arena in 2009.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom