For 45 years, the Canadian government investigated unidentified flying objects (UFOs). Several of its departments and agencies collected sighting reports of UFOs in Canadian airspace from 1950 to 1995. These investigations started during the Cold War, spurred by fears of Soviet incursions. What began as a military question eventually became a scientific one. From the start, however, the government was reluctant to study this topic. It devoted few resources to it, believing UFOs to be natural phenomena or the products of “delusional” minds. By contrast, many Canadian citizens were eager for information about UFOs. Citizens started their own investigations and petitioned the government for action. In 1995, due to budget cuts, the government stopped collecting reports altogether. For their part, citizen enthusiasts have continued to investigate UFOs.

© Government of Canada. Reproduced with the permission of Library and Archives Canada (2020).

Project Magnet and Project Second Story

The modern era of UFO sightings began in 1947. On June 24, pilot Kenneth Arnold reported seeing nine shiny flying discs over Mount Rainier in Washington State. Canada’s first postwar UFO sightings occurred that same year. The Cold War was just underway. The Canadian government was at first concerned that UFOs might present a security threat if they turned out to be advanced Soviet technology. In the early 1950s, the government launched two separate projects devoted to UFOs. Both came about for the sake of caution and to allay public concern.

Project Magnet (1950–54) was the brainchild of Wilbert Smith, a radio engineer with the Department of Transport. Smith undertook experiments to determine whether UFOs flew using magnetic energy. He also launched a balloon into the night sky in order to solicit sighting reports and test their accuracy. Finally, he built a UFO observatory at Shirley’s Bay, a restricted military site west of Ottawa. Smith’s experiments were inconclusive. He had also come to believe that UFOs were extraterrestrial (from beyond planet Earth). He began drawing bad publicity with this view, so the Department of Transport shut down Project Magnet.

The government wanted to establish an official position on UFOs. To this end, the Defence Research Board set up Project Second Storey (1952–54). This short-lived committee was chaired by Peter Millman, an astronomer with the Dominion Observatory. Millman was skeptical of UFOs. In his opinion, they were not extraterrestrial in origin and the project was a waste of time and resources. The committee did not investigate any sightings; it acted as an advisory body only. It worked to standardize a UFO sighting form. It also attempted to debunk sightings as nothing other than misidentified natural phenomena, such as meteorites. Project Second Storey concluded that UFOs, if they were real at all, were “not amenable to scientific inquiry.”

Military intelligence decided that the Soviet Union was likely not responsible for the objects. UFOs then became a scientific question. From the mid-1960s onward, the RCMP was the main agency responsible for collecting reports from witnesses. Government scientists, however, were reluctant to engage with the issue. Most reports were filed away and forgotten.

Civilian Response

Citizens across the country took a keen interest in UFOs. Many wrote letters to the government requesting information. These requests ranged from polite and deferential, to bizarre, demanding and hostile. Citizens wanted to know what UFOs were. They also asked whether UFOs posed a threat to national security and what the government was doing about them. Some accused the government of a cover-up, implicating it in conspiracy theories. There were those who claimed to have seen a UFO and were convinced they were extraterrestrial objects. Government officials stated that such ideas were nonsense and assured the citizens there was nothing to fear.

Many citizens thought the government was giving them the “go-around” and “doublespeak.” They took it upon themselves to investigate UFOs. Beginning in the 1950s, people formed UFO clubs. They met in homes, hotels, church halls and auditoriums to speculate about the objects. For example, Wilbert Smith (of Project Magnet) formed the Ottawa Flying Saucer Club. Others formed the Vancouver Area Flying Saucer Club, which hosted prominent ufologists and distributed recordings of their talks. Along with media accounts, these sorts of clubs were one of the main ways citizens accessed information about UFOs.

Some citizens went even further. They established UFO investigation groups to find out exactly what the objects were. Many of these groups existed from the 1960s until the 1980s. In Scarborough, Ontario, there was the Canadian Aerial Phenomena Investigations Committee. A group called Canadian UFO Research operated in Oshawa, Ontario. Winnipeg, Manitoba, had the Canadian Aerial Phenomena Research Organization. In Montreal, Quebec, there was the UFO Study Group. These groups usually lobbied the government for more action and disclosure of information. Sometimes they even lobbied for funds to carry out investigations.

Access to Information

Beginning in the late 1960s, the focus shifted for UFO enthusiasts. Before this time, citizens were interested in what UFOs were and who (or what) operated them. Afterward, citizens began decrying government secrecy more generally. UFO investigation groups called for more government transparency at a time when the Official Secrets Act severely restricted what documents they could access. Citizens wanted better access to information so they could collect and analyze UFO reports themselves. These citizen investigators no longer trusted the government to carry out the task. This view was not limited to those who believed the government was involved in a conspiracy to hide the truth about extraterrestrial visitation. Some citizens simply felt that UFO investigations would be better handled by dedicated amateurs, through a kind of citizen science.

In 1983, the Access to Information Act came into effect. UFO investigators began filing formal requests for information. The items released confirmed that the government was not hiding any documentation about extraterrestrials. In fact, the only information withheld were personal details like the names and addresses of witnesses. Those who filed requests did receive documents like sighting reports, but never any proof of UFO visitation. The absence of such proof did not deter many civilians from their investigations.

In 1995, due to budget cuts, the government and its agencies stopped collecting reports altogether. This meant that UFO enthusiasts and witnesses began turning instead to civilian investigations to report their sightings. One such investigation is the Winnipeg-based organization Ufology Research, which produces the annual Canadian UFO Survey. A digitized collection of the federal government’s UFO documents is available on the Library and Archives Canada website.

Three Physical Cases

Three UFO reports from the year 1967 were particularly unusual. They drew some concern even from the skeptical Canadian government. This was the year of Canada’s Centennial celebrations, which included the construction of a UFO landing pad in St. Paul, Alberta. The time was ripe for a fresh look at UFOs. The cases of the Falcon Lake Incident, the Duhamel Crop Circles and the Shag Harbour Crash provided not just new evidence to consider, but physical evidence to inspect, which nearly all other reports lacked.

Falcon Lake Incident

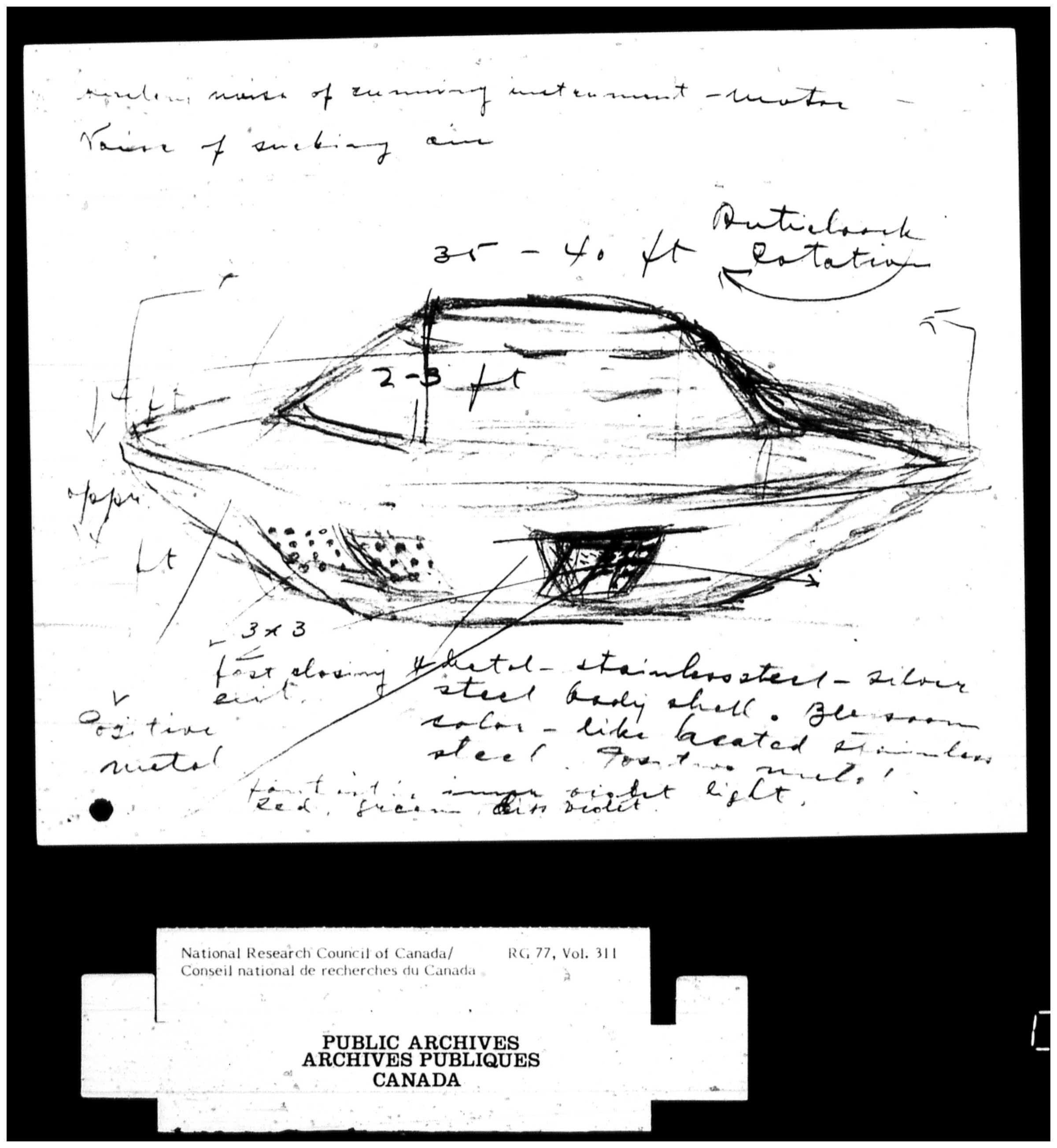

In May 1967, amateur prospector Stefan Michalak ventured into the bush near Falcon Lake, Manitoba. He would reemerge claiming he had not only seen two UFOs, but that one had severely burnt him and given him radiation poisoning. Michalak recounted seeing the two vessels in plain sight, one of which zoomed off while the other landed in front of him. He approached the craft and tried to hail its occupants. Eventually, it took off again, blowing hot air out of an exhaust panel. This set fire to Michalak’s shirt and left a grill-patterned burn on his chest. Authorities disbelieved his account until he showed them the site where he claimed the craft had also burnt away vegetation. For years, Michalak would suffer from his chest burn, which intermittently reappeared.

Duhamel Crop Circles

During a rainy night in August 1967, a series of crop circles mysteriously appeared in a farmer’s field in Duhamel, Alberta. The local press was immediately notified, followed by a UFO club in Edmonton, and then national media. A scientist from a nearby military facility investigated, finding the field trampled by visitors. The six crop circles appeared to contain tread marks as if from a tire, but only on small portions of the circles. Despite this, the scientist concluded that the circles were not a hoax. A soil sample test proved inconclusive. In the end, the scientist admitted that the marks appeared as if made by a hovering aircraft, but could not conclude the investigation one way or another.

© Government of Canada. Reproduced with the permission of Library and Archives Canada (2020).

Shag Harbour Crash

The year’s events culminated in October 1967 with a crash in the fishing village of Shag Harbour, Nova Scotia. Close to midnight, local RCMP received several calls about a craft downed in the harbour. The craft made a whistling sound and a flash as it hit, and then floated on top of the water for several minutes. Some witnesses, which included RCMP officers, recall seeing glittering yellow foam surround it. Before a boat could reach the craft, it sank below water. A dive team searched the harbour but could not find evidence of any wreckage. Like the Duhamel and Falcon Lake reports, the Shag Harbour case remains unsolved.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom