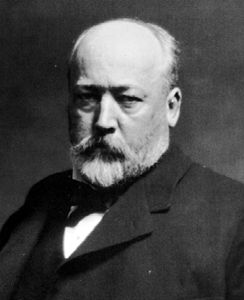

Sir William Cornelius Van Horne, telegrapher, railroad executive, artist (born 3 February 1843 in Chelsea, Illinois; died 11 September 1915 in Montreal, Quebec.) In January 1882, Van Horne was appointed general manager of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR), responsible for completing the transcontinental line. His leadership of the CPR led to a streamlined organization, new routes, rapid line construction, and its completion in 1885. Van Horne also initiated the creation of luxury hotels along the CPR line and the Canadian Pacific Steamship Company that linked Vancouver and Hong Kong. (See Railway History in Canada.)

Early Life

Van Horne was born the oldest of five children in Chelsea, Illinois, a tiny settlement south of Chicago. When Van Horne was eight years old, his parents moved to Joliet where his father, Cornelius Van Horne, could practice law and the children could attend school. His father was elected mayor of Joliet.

The family suffered hard economic times when in July 1854, his father died of cholera. Van Horne left school at age 14 to earn money for his family and among his many jobs was carrying messages for a telegraph company.

In 1857, Van Horne became a telegrapher with the Illinois Central Railroad. Insatiably curious and a voracious reader, Van Horne learned all facets of the railroad industry. After seeing a railroad executive arrive at a station in a luxurious private rail car, he determined to become a railroad superintendent.

Early Railroad Career

In 1862, Van Horne became a telegraph operator and ticket agent with the Chicago and Alton Railroad. The 19-year-old was soon responsible for keeping numerous trains carrying Civil War troops, passengers, and freight running on time on crisscrossing lines. In 1870, Van Horne was appointed the Chicago and Alton Railroad’s telegraph assistant superintendent. In 1872, he was promoted to superintendent of transportation. That same year, he was appointed general superintendent of one of the company’s subsidiaries, the struggling St Louis, Kansas City and Northern Railroad. At age 29, he had become the world’s youngest railroad superintendent. In March 1867, Van Horne married Lucy Adaline Hurd, the daughter of a railroad civil engineer.

Upset by a lack of support from the parent company, Van Horne resigned in June 1874 and became superintendent of the failing Southern Minnesota Railroad. Several bold initiatives reversed the company’s fortunes. In October 1879, he returned to Chicago and Alton as its general manager. He involved himself in every aspect of the business including creating more efficient line construction, freight and passenger schedules, railcar construction, and even the quality and serving sizes of onboard meals. It was widely accepted that Van Horne was America’s best railroad operator.

In January 1880, he became the general superintendent of the Chicago, Milwaukee, and St. Paul Railroad. He again demonstrated a hands-on management style that cut costs while implementing ideas to carry more freight and improve passenger service.

Canadian Pacific Railway

Canada’s first prime minister, Sir John A. Macdonald, knew that if the young country created by Confederation in 1867 was to thrive, it needed to expand west, and that a transcontinental rail line was essential to that effort. He made a deal with British Columbia’s government that if the colony joined Canada as a province, he would have a rail line to Victoria in ten years. Surveying began in 1871 but, ten years later, progress on the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) was slow as it was impeded by political, management, and financing problems.

Macdonald approved Van Horne to become the CPR’s new general manager, ignoring those who worried about an American leading Canada’s most important undertaking. Van Horne’s family moved to Montreal, and he assumed his post on 1 January 1882.

Among Van Horne’s first decisions was to fire his entire engineering staff. He then changed the CPR’s route to run closer to Lake Superior and cross the Rocky Mountains at Kicking Horse Pass. Van Horne reorganized the CPR’s governance and management structure. He directly oversaw the transportation of enormous stores of building materials from various sources to numerous work sites. He often appeared at those remote sites without notice to assess progress and shout orders. While the previous construction season had seen the laying of 259 km of new track, in the first year of Van Horne’s leadership, the CPR laid 671 km in Ontario, Quebec, and across the prairies.

Van Horne worked long hours addressing supply and labour shortages, strikes, natural disasters, and a constant shortage of funds. When Louis Riel led the North-West Resistance in the spring of 1885, Van Horne organized the quick deployment of troops to Saskatchewan. The military action led to a welcome infusion of investment in the CPR.

On 14 May 1885, Van Horne was appointed to the company’s board of directors and, while continuing as general manager, he also became its vice president. On 7 November 1885, the last spike was driven at Craigellachie, British Columbia, symbolizing the CPR’s completion.

Van Horne’s innovations continued with his initiating and helping to design luxurious Canadian Pacific hotels along the line to draw travellers; some of which, such as Quebec City’s Château Frontenac and Ottawa’s Château Laurier, remain iconic destination spots. He also oversaw the completion of telegraph lines across Canada that provided quick communications. In 1891, Van Horne created the Canadian Pacific Steamship Company. He secured three British ships that carried mail and freight while offering luxury travel between Vancouver and Hong Kong.

Interests and Investments

Van Horne was knighted in 1894. For years he had invested wisely in many companies and by the turn of the century he was serving on 40 corporate boards. In 1900, he became president of the Cuba Company, later the Cuba Railroad Company. He organized the building of a rail line in Cuba while taking other initiatives that helped develop the country’s economy. His enormous wealth allowed him to purchase luxurious homes in Montreal, New Brunswick, and Cuba.

He enjoyed gardening, playing violin, digging for fossils, sumptuous meals, expensive cigars, and all-night poker games. He donated generously to galleries, hospitals, and public parks.

Van Horne was also an artist and art collector. In his youth, he copied the text and illustrations of geological books he couldn’t afford. His correspondence sometimes included sketches of certain details.

Death

Van Horne contracted rheumatism in 1913 which affected his mobility and strained his health. He died on 11 September 1915, in Montreal. After a funeral in Montreal, his body was transported by a CPR train for burial in Joliet, Illinois.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom