Canadian forces were involved in the Asia-Pacific theatre of the Second World War from its outset. At the same time as the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, other Japanese forces attacked Hong Kong and several other British and Allied bases in the region. Although the main Canadian war effort was against Germany and Italy in the North Atlantic and Western Europe, all three services also employed limited resources in the Asia-Pacific Theatre.

West Coast Defences

Canada began to reinforce its west coast defences in 1939 and intensified its efforts as tensions grew with Japan. After Japan attacked various outposts of western countries in Asia and the Pacific on 7 December 1941, Canada strengthened its land, sea and air defences in the Pacificregion. These grew throughout the war and eventually reached two army divisions, as well as several air squadrons and warships.

Fearing a Japanese invasion of the west coast, the army also organized an auxiliary corps, known as the Pacific Coast Militia Rangers (PCMR), in February 1942. By August 1943, the unit had almost 15,000 men in 115 companies stretching from the Queen Charlotte Islands (Haida Gwaii since 2009) to the American border. The PCMR consisted of residents of the coastal region with local knowledge. Their purpose was to provide information to the regular forces of any Japanese activities and to assist in resisting minor enemy attacks. Training was limited and consisted largely of rifle practice. The Rangers wore khaki denim uniforms with a distinctive armband.

Hong Kong

In Hong Kong, the small British garrison included 1,975 Canadians from Quebec’s Royal Rifles of Canada and the Winnipeg Grenadiers, plus a brigade headquarters and a 100-man reinforcement company for each battalion, as well as signals, medical, dental, service corps, ordnance, provost and postal detachments. The Canadians had arrived in Hong Kong on 16 November 1941 to strengthen the island colony's defences. On 7 December, the Japanese army attacked in overwhelming numbers. The beleaguered garrison had little hope but fought courageously. Among the Canadian defenders was Company Sergeant-Major John Osborn of the Winnipeg Grenadiers, who was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross after he deliberately fell on a grenade just before it exploded, thereby saving the lives of several comrades. The Canadian commander, Brigadier John Lawson, was killed in front of his command post. On Christmas Day, the Allied forces in Hong Kong surrendered. The hard-fought battle resulted in 290 Canadian deaths. (See Battle of Hong Kong.)

Prisoners of War

After the surrender of Hong Kong, 1,685 Canadians became prisoners of the Japanese. They remained prisoners for almost four years and were subjected to systematic cruelty. They were forced to carry out gruelling labour while being beaten frequently and fed inadequately. Before the emaciated and diseased survivors were freed in 1945, another 264 men had died. Most of those who returned to Canada suffered serious disabilities because of their prisoner of war experience; many died premature deaths.

Japanese Canadian Internment

Two months after the fall of Hong Kong and amid growing hysteria, the Canadian government bowed to public pressure and ordered the removal of all Japanese Canadians living within 160 km of the Pacific Coast. This was supposedly a national security measure, yet neither the military nor the RCMP viewed them as a threat. About 21,000 Japanese Canadians — 77 percent of them British subjects — were shipped to detention camps in the interior of British Columbia or to Prairie farms. The government later seized and sold their properties and businesses below fair market value. In 1945, Japanese Canadians were given a choice: deportation to war-torn Japan or dispersal east of the Rockies. Most moved east. (See Internment of Japanese Canadians.)

Canadians in the British Forces

Although the exact numbers are unknown, several thousand Canadians served in the British armed forces in the war against Japan. In particular, the numbers of Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) members who served in the Royal Air Force (RAF) are difficult to ascertain. RAF authorities believed in mixed Commonwealth aircrews and assigned Canadians accordingly. This resulted at least 7,500 Canadian airmen, ground crew and radar personnel serving in RAF squadrons that fought against Japanese forces in Southeast Asia.

Many Canadians fought with Fourteenth British Army in northern Burma and eastern India. Major Charles Hoey of Duncan, British Columbia, had joined the British Army in the mid-1930s. In February 1944 in Burma, Hoey led his infantry company in an assault on a Japanese-held hill. He was killed in the action, but his gallantry earned him the Victoria Cross, having previously been awarded the Military Cross.

Lieutenant-Commander Bruce Wright of Quebec City conceived, trained and led the Sea Reconnaissance Unit, a group of frogmen (underwater swimmers) from all three services who spearheaded British assaults across Burmese rivers. Among other Canadians in the unit was Flight Lieutenant George Avery of Ottawa. For his bravery during the crossing of the Irrawaddy River, Avery earned the first Military Cross ever awarded to a frogman.

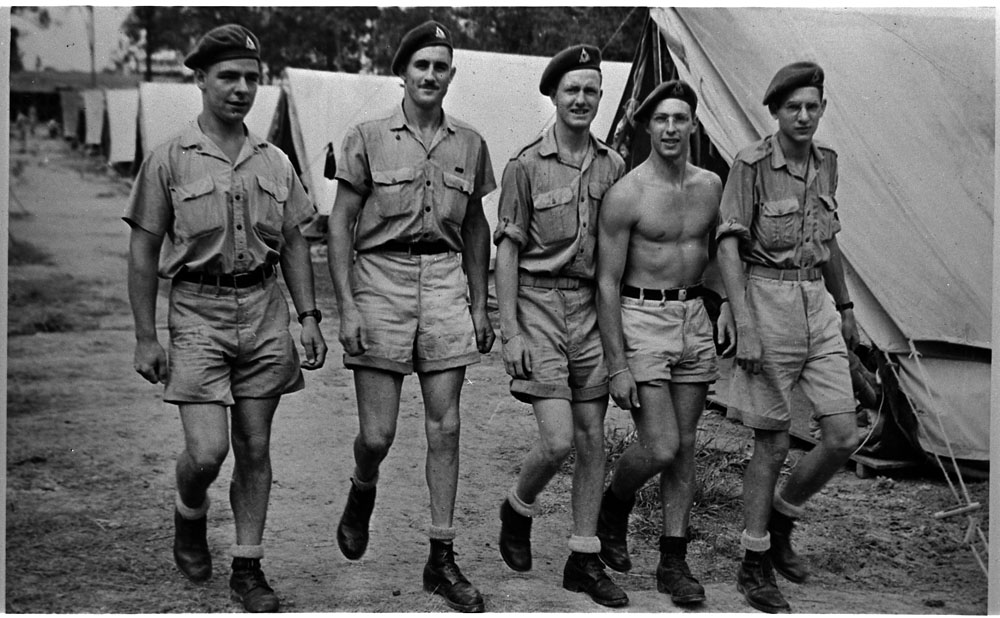

Force 136 was a British Special Operations Executive unit that operated in Southeast Asia and trained and supported local resistance movements to sabotage Japanese supply lines and equipment. Although most of the unit’s members were Southeast Asians, about 150 Chinese Canadians served in it. They blended in easily with local populations and spoke Cantonese, which was used throughout the region. Force members were trained in skills such as demolitions, stalking, parachuting, radio operation, surveillance, silent killing and jungle survival.

A few of the Force’s members were deployed on operations in Burma, Borneo and Malaya. Several of them stayed in Southeast Asia after the war to help liberate Japanese prisoner of war camps and maintain law and order. Their service was a major factor in influencing the Canadian government to grant Chinese-Canadians full citizenship rights in 1945.

Lieutenant Robert Hampton Gray of Trail, British Columbia, was among a small group of Canadians who flew in the Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm. On 9 August 1945, he flew his Corsair dive bomber off HMS Formidable to attack Japanese shipping near the Home Islands. Gray spotted a Japanese ocean escort vessel in Onagawa Bay and dove to attack. Although his aircraft was hit repeatedly by anti-aircraft fire, he continued his attack. Gray’s bombs struck the vessel amidships and it quickly sank. He crashed a short distance away and was subsequently awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross, the last one awarded to a Canadian to date.

No. 413 General Surveillance Squadron

No. 413 Squadron RCAF was attached to the RAF’s Coastal Command and equipped with Consolidated Catalina flying boats. In the face of Japan’s advances into Southeast Asia, it moved from Scotland to Ceylon (modern Sri Lanka) in March 1942. A week after its arrival, its commander, Squadron Leader Len Birchall, and his crew were on their first patrol. They sighted a Japanese strike carrier fleet some 560 km south of Ceylon heading toward the island. Birchall’s aircraft was shot down by Japanese fighters, but not before his radio operator had warned Ceylon of the approaching Japanese. Three of the crew were killed, but Birchall and five remaining crewmen were captured, beaten and imprisoned. They survived the war.

When Birchall’s message was received, the British cleared Colombo harbour of shipping, but RAF fighter squadrons were slower to react and were still on the ground when Japanese aircraft showed up the next morning. The squadrons, which included several Canadians, scrambled to meet the attacking Japanese and drove them off. For his feat, Birchall earned the nickname “Saviour of Ceylon.” After the war, he was decorated for his distinguished flying and his courage and leadership in resisting his Japanese jailors during years of imprisonment.

Aleutian Islands

In June 1942, approximately 8,500 Japanese soldiers occupied the Alaskan Aleutian Islands of Attu and Kiska. On 20 June, a Japanese submarine shelled Estevan Lighthouse on the west coast of Vancouver Island, causing minor damage. Although the Japanese in the Aleutians were still 3,000 kilometres from Vancouver, and the attack on the lighthouse was little more than an act of bravado, the threat could not be ignored. Canada committed two army divisions and considerable air and naval forces to the defence of the West Coast, while the Americans rushed reinforcements to Alaska.

In May 1943, the Americans launched a campaign to retake Attu, supported by Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) ships and RCAF aircraft. The Japanese fought to hold the island, which fell after 20 days. For Kiska, Canada provided 13 Infantry Brigade Group, as well as naval and air forces and members of the American-Canadian First Special Service Force. On 15 August, when Canadians and Americans landed on Kiska, they found the Japanese had abandoned the island.

After the Japanese assault on the Aleutians, the only other attacks occurred from January to March 1945 when the Japanese launched incendiary balloon bombs. Their hope was that the ballons would drift over western North America and set the vast Pacific Northwest forests on fire. An estimated 1,000 of the 10,000 balloons launched arrived in North America, some of which made it as far as the Prairies; they caused little damage, however.

Alaska Highway

Fears of a Japanese invasion also prompted the building of the first road link between Alaska and the rest of the continent. The 2,451 km Alaska Highway was built between March and November 1942 and cost $185 million; it was the most expensive American project of the war. Although the Canadian government did not contribute to the highway’s costs, it provided funding to construct airfields and strips, buildings, telephone systems and other facilities.

A rough preliminary road was constructed by about 11,000 US Army engineers and around 16,000 Canadian and American civilian workers. Included among the engineers from the United States were almost 3,700 Black soldiers, who faced discrimination and segregation even while they built the road. Among other restrictions, Black soldiers were not allowed to enter towns along the route, were housed in wilderness areas and had to use picks and shovels instead of heavy machinery. The highway connected Dawson Creek, British Columbia, with Delta Junction, Alaska, through virgin forest, muskeg and five mountain ranges. The following year it became a permanent, all-weather, gravelled road. The highway also provided a corridor for an oil pipeline and a telephone and telegraph line. By the time it was completed, the enemy threat had receded, but the road has remained an essential transportation artery.

Empress of Asia

In January 1941, the British government requisitioned the Canadian Pacific Railway ocean liner Empress of Asia as a troop carrier. After the addition of several large guns, the ship made a few voyages before sailing to Singapore in early 1942. On 5 February, Japanese aircraft bombed the Empress of Asia near Singapore and set it on fire, forcing the crew to abandon ship. Many of them subsequently became prisoners of war and lost their lives during captivity.

435 and 436 Transport Squadrons

Nos. 435 and 436 Transport Squadrons flew Dakotas in support of Fourteenth British Army in Burma. Formed in India in mid and late 1944, they flew air supply missions until the end of the war and carried more than 56,000 tonnes of freight and about 39,000 soldiers, casualties and other passengers. Seven aircraft were lost on operations and several aircrew killed.

Merchant Navy

Canadian Merchant Seamen served throughout the Asia-Pacific Theatre carrying troops and cargoes in Canadian and Allied ships. Canadian seamen were killed on the Jasper Park, Fort Longueuil, Lianash and fourteen other ships during Japanese attacks. (See also Merchant Navy of Canada.)

Mule Skinners

On 1 February 1944, the British government asked Canada to provide mule handlers (known as “skinners”) to accompany shipments of mules from New York to Karachi for the Indian army. Mules were needed to help transport supplies across the mountainous terrain of eastern India and western Burma. Canada agreed, and four shiploads of mules were sent between March 1944 and April 1945. In total, 179 Canadians made the journey and escorted about 1,600 mules. Three of the escort parties came from the Veterans Guard of Canada, with the fourth from No. 2 General Employment Company.

Radar Technicians

In 1944, Canada sent Canadian-designed and -manufactured radar equipment for anti-aircraft artillery to Australia. The radars were used in northern Australia, New Guinea and other island outposts. In March, Australia requested technicians to both man these sets and instruct others on their use. Canada sent 73 all ranks, who arrived in September. In the summer of 1945, some of the technicians were sent to other locations.

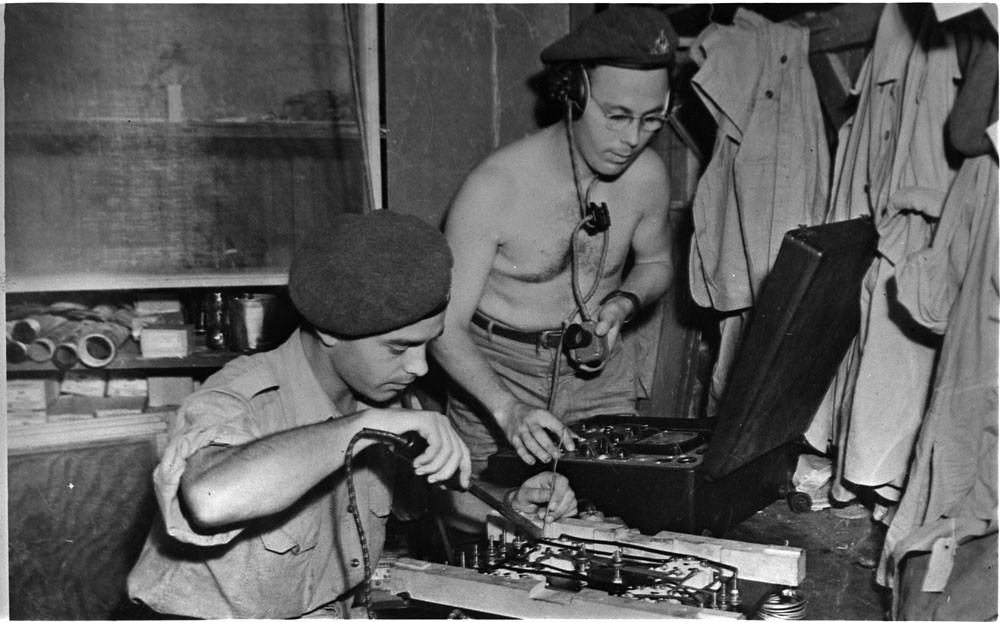

No. 1 Canadian Special Wireless Group

On 19 July 1944, Canada authorized the establishment of No. 1 Special Wireless Group to intercept and decrypt Japanese radio messages. Its 336 men were divided into two sections, 291 in signals and 45 in intelligence. The unit arrived in Australia on 15 February 1945 and proceeded to Darwin on the country’s north coast, where it began working on 30 April. On average, the group intercepted 1,200 enemy messages a day. The Americans had earlier broken the Japanese Kona code, which was then translated into English by unit cryptographers who were the sons of former Canadian missionaries in Japan. When the war ended on 15 August, General Douglas MacArthur, Allied supreme commander South West Pacific Area, asked the group to remain to intercept Japanese diplomatic radio messages. The unit continued to operate until 11 October, when it began its return to Canada, although some soldiers remained longer. The group’s members were sworn to secrecy, and the details of their activities were only declassified in 1986.

HMC Ships Uganda and Prince Rupert

After the war in Europe ended, the Allies concentrated on Asia and the Pacific. The first Canadian force to make its presence felt was the Royal Canadian Navy. The cruiser HMCS Uganda joined the British Pacific Fleet (BPF) in early 1945 and participated in the Allied bombardment of Okinawa in April and Truk in June. After Germany surrendered in May, the crew were given the opportunity to volunteer for further service; the majority voted to return home, however, to the country’s and the navy’s great embarrassment. Meanwhile, the armed merchant cruiser HMCS Prince Robert, which had helped transport Canada's troops to the ill-fated defence of Hong Kong in 1941, returned to the Pacific theatre and assisted in the liberation of prisoners of war captured at Hong Kong.

Canadian Pacific Force

Even before the war in Europe ended, plans were being made for a large Canadian contribution to the war against Japan, which was expected to last well into 1946. This included preparations for Operation Downfall, an invasion of the Japanese Home Islands in the fall of 1945. The largest component was the Canadian Army Pacific Force (CAPF). It consisted of 6th Canadian Infantry Division, a tank battalion and appropriate corps and army troops, organized along US Army lines. Major-General Bert Hoffmeister, Canada’s most successful divisional commander of the war, was selected to command the division.

RCAF plans for the war against Japan included the contribution of heavy bomber squadrons of Lancasters to Tiger Force, the RAF’s strategic bomber commitment, plus fighter, transport and other types of squadrons. As the war neared its end, the number of squadrons was reduced to eight bomber squadrons in four wings, commanded by Air Vice-Marshal Charles Slemon.

The RCN was the last service to plan for Operation Downfall; its contribution to the British Pacific Fleet was to consist of two light fleet carriers, two light cruisers, an anti-aircraft cruiser, 11 destroyers, 36 frigates and eight corvettes, plus a reserve of six destroyers, 20 frigates and four improved corvettes.

All preparations stopped when the atomic bombs were dropped on Japan, causing the Japanese to surrender unconditionally on 15 August 1945.

Manhattan Project

Canadians helped Americans develop the world’s first nuclear reactors and atomic bomb. Canadian scientists had been assisting the British in this research and continued their assistance in 1943, when the British program merged with the American one, known as the Manhattan Project. Canadians made three major contributions to the Manhattan Project: the supply of processed uranium, the extraction and production of plutonium and the provision of technical personnel and facilities.

End of the War

On 2 September 1945, the formal surrender documents were signed between representatives of the Allies and the Japanese. The ceremony took place aboard the American battleship USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay. Canada’s military representative in Australia, Colonel Lawrence Cosgrave, became the lowest-ranking representative to sign on behalf of his country. He was a career soldier with distinguished service during the First World War, when he was blinded in one eye.

The documents included a separate line for each Allied representative to sign. When it was Cosgrove’s turn, he advertently signed on the line below the one for Canada, which was intended for the French signatory. The knock-on effect resulted in the New Zealand representative signing in a blank space at the bottom of the page. When the Japanese voiced concerns about the legitimacy of the document, General MacArthur’s chief of staff hurriedly made corrections with his fountain pen and sent the Japanese on their way.

With the signing of the surrender document, the Second World War was officially over.

Campaign Medals

Pacific Star

Awarded for one day or more of operational service in the Pacific Theatre between 8 December 1941 and 2 September 1945. If later entitled to the Burma Star, the BURMA clasp is worn instead of the medal. Canadians received 8,000 Pacific Stars, 900 with the BURMA clasp.

Burma Star

Awarded for one day or more of operational service during the Burma Campaign between 11 December 1941 and 2 September 1945. If later entitled to the Pacific Star, the PACIFIC clasp is worn instead of the medal. Canadians received 5,500 Burma Stars, 1,000 with the PACIFIC clasp.

Hong Kong Clasp

Approved in 1995 for veterans of Hong Kong to wear on the ribbon of the Canadian Volunteer Service Medal.

Battle Honours

A battle honour is the formal recognition of navy ships, certain types of army units and air force squadrons in a battle, campaign or war. Canadian units received several honours for the Asia-Pacific Theatre.

Royal Canadian Navy

Aleutians, 1942 – HMC Ships Prince David, Prince Henry, Prince Robert

Aleutians, 1942–43 – HMC Ships Vancouver, Dawson

Okinawa 1945 - HMCS Uganda

Canadian Army

Hong Kong – Royal Rifles of Canada, Winnipeg Grenadiers

South-East Asia, 1941 - Royal Rifles of Canada, Winnipeg Grenadiers

Royal Rifles of Canada badge with year date 1941 - Honorary Distinction awarded to the 7th/11th Hussars for reinforcing the Rifles on mobilization.

Royal Canadian Air Force

Pacific Coast, 1941–45 – 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 115, 120, 147, 149 Bomber Reconnaissance Squadrons, with appropriate year dates (earned but never awarded as these squadrons were disbanded before the war ended).

Aleutians, 1942–43 – 111 Fighter Squadron

Aleutians, 1943 – 14 Fighter Squadron

Ceylon, 1942 – 413 General Reconnaissance Squadron

Eastern Waters, 1942–44 – 413 General Reconnaissance Squadron

Burma, 1944–45 – 435 Transport Squadron

Burma, 1945 – 436 Transport Squadron

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom