On Christmas Day 1895, a young man was shot in the leg during an altercation in Montreal. His surgeon was unable to locate the bullet by exploring its entry site. When the wound began to cause trouble, the surgeon wondered if a remarkable new discovery, X-ray imaging, might be able to locate the projectile. He turned to physicist John Cox for assistance, leading to the performance of Canada’s first medical X-ray examination on 7 February 1896. This event marked the introduction and subsequent dissemination of a new tool to diagnose and treat patients in Canada.

Context

On 8 November 1895, German physicist Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen (1845–1923), working in his laboratory in Würzburg, discovered a new type of ray that he provisionally called the “X ray,” signifying that its nature was then unknown. He noted that X rays were capable of penetrating various solid materials, and in December 1895, he made a crude but immediately recognizable X-ray image of a human hand, believed to be that of his wife, Anna Bertha. Röntgen’s (anglicized as Roentgen) remarkable discovery was reported on the front page of the Vienna Presse on 5 January 1896, and within days became international news. Many physics laboratories in the developed world were equipped with the gas tubes and induction coils required to generate X rays, and soon after this press report scientists in Europe and North America were replicating Röntgen’s findings. The first medical radiograph in Canada was made at Montreal’s McGill University by physicist John Cox on 7 February 1896.

John Cox and the First Medical X ray in Canada

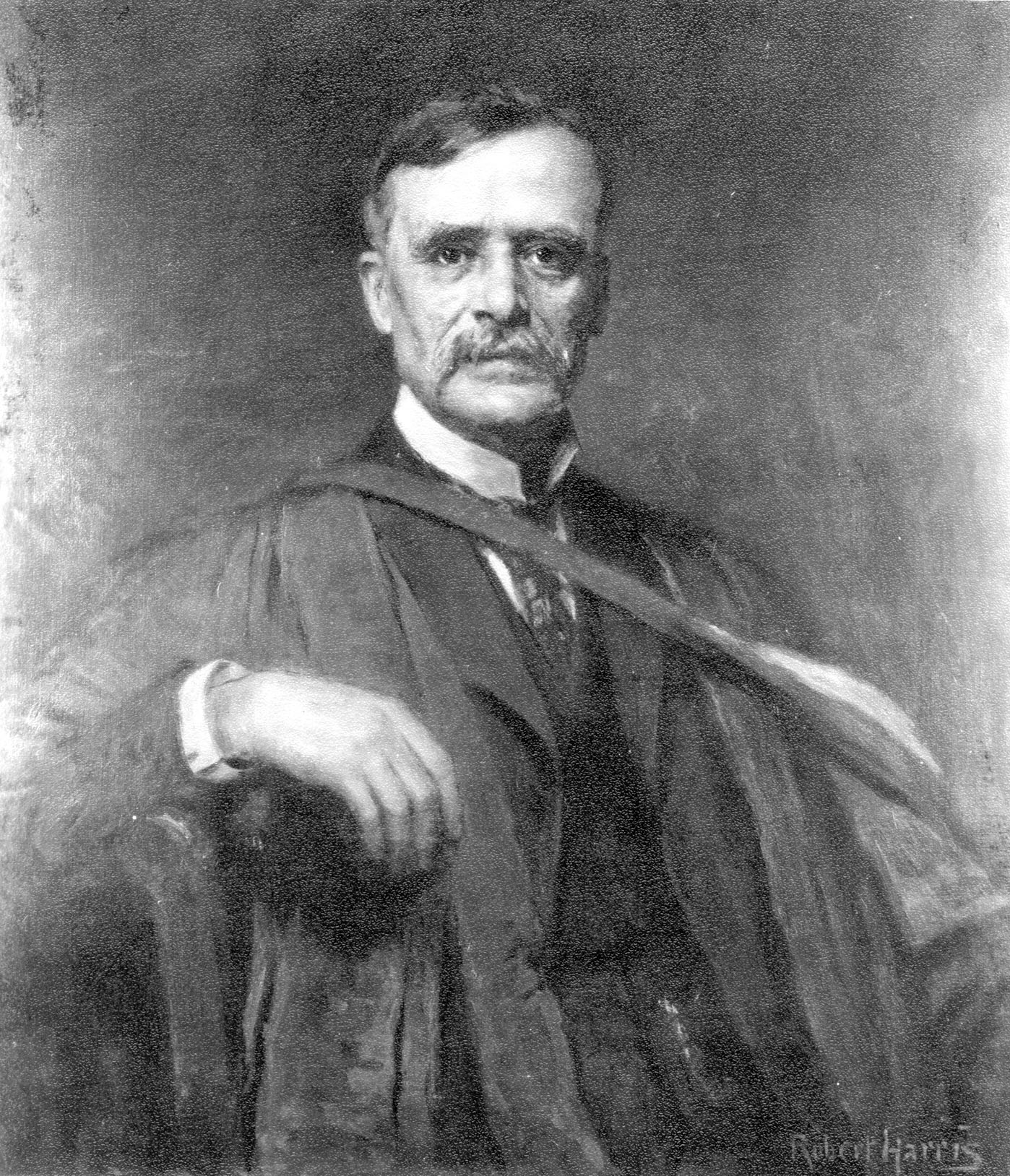

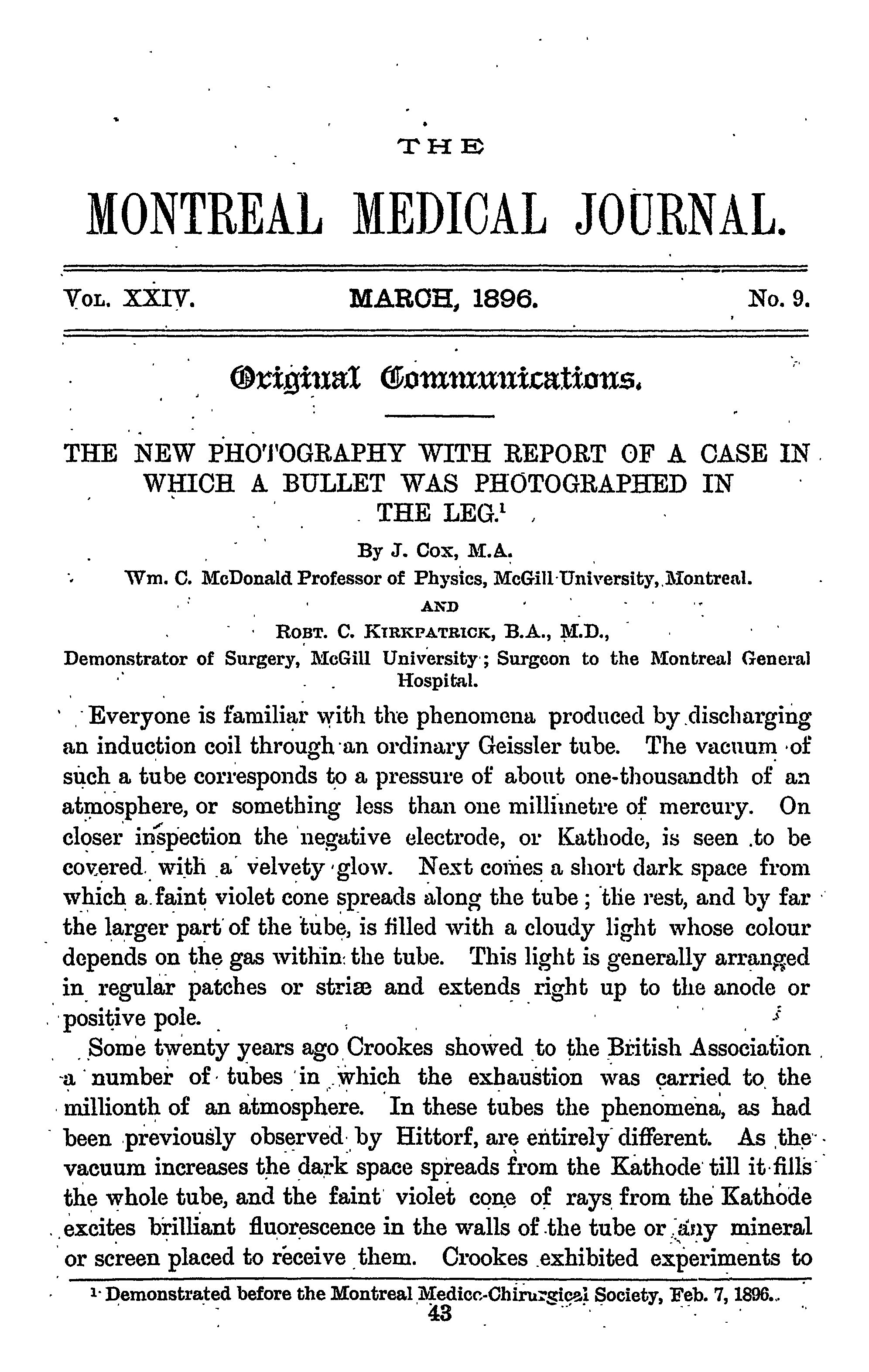

John Cox (1851–1923), then director of McGill University’s Macdonald Physics Laboratory, had assembled an apparatus to produce X rays in early February 1896, producing excellent images of the hands of his laboratory assistants. (See also Physics.) Concurrently, Robert Kirkpatrick, a surgeon at Montreal General Hospital, was caring for a young patient, Tolsen Cunning, who had been shot in the leg during a dispute on Christmas Day 1895. The surgeon had been unable to find the bullet by probing, leaving the wound to heal with the projectile in place. When the injury began to trouble his patient, Kirkpatrick consulted Cox to see if the bullet might be located using the new X-ray imaging. Accepting Kirkpatrick’s challenge, Cox subjected Cunning’s immobilized limb to a 45-minute exposure. As reported the next day in the New York Journal, after the plate was taken to the darkroom for development, “Professor Cox reappeared. One could detect at once, from the beaming countenance, the success of the experiment.”

Cox discerned the flattened bullet lying in the soft tissues of the calf between the tibia and fibula, 3 cm below its entry point. Kirkpatrick was able to remove it successfully, and his patient left the hospital after 10 day’s recovery. Cox and Kirkpatrick reported their findings in the March 1896 issue of the Montreal Medical Journal. Cunning later sued his assailant, George Holder, and the X-ray plate was used as evidence in court. Thus, the radiograph produced by Cox on 7 February 1896 is considered (i) the first clinical radiograph made in Canada, (ii) the first in North America to be used as an adjunct to surgery, and (iii) possibly the first in the world to be used in jurisprudence. Cox and his physicist colleague, Hugh Callendar, the Macdonald Professor of Experimental Physics, continued their early experiments with X rays for a short time, but soon moved on to other endeavours. Their historic plate no longer exists.

Growth of Radiology in Canada

The earliest X-ray workers were a diverse group consisting of physicians, physicists, engineers, photographers, electricians, and others with the technical backgrounds and access to the equipment required to generate X-rays. Radiographic imaging quickly caught the public’s attention, and an entrepreneurial person whose identity and background are lost to history made radiographs of the hands of curious passers-by on Yonge Street in Toronto in 1896. It was gradually realized that there were adverse effects to biological tissue from prolonged exposure to X-radiation and that protection was needed. The International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) was founded in 1928. Its influence led to the first publication of specific Canadian recommendations on radiation protection around 1945.

Although the population of Canada at the time of Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen was small, and communication not always easy, a few far-sighted physicians in each province recognized the need for improved medical X-ray diagnosis, as well as the potential for growth in their own medical expertise. These early experts became known as radiologists or roentgenologists. Professor Gilbert Girdwood (1832–1917), an English-born surgeon, was appointed the first director of the new Medical Electrical Department of Montreal’s Royal Victoria Hospital in 1901. Girdwood is considered the first Canadian radiologist and the grandfather of Canadian radiology.

Initially, these fledgling radiologists looked to Quebec and Ontario for education, but over the next decades, expertise in X-ray interpretation spread to the other provinces, often in reaction to external events. For example, radiology in Alberta began in Medicine Hat in response to the needs of Canadian Pacific Railway employees. In Nova Scotia, the Halifax Explosion of 1917 brought an urgent need for enhanced medical care and X-ray diagnosis. The Canadian Association of Radiologists (CAR), founded in 1937, became the advocacy group that ultimately brought about the formal recognition of Diagnostic Radiology as a distinct medical specialty by the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, which oversees the education of medical specialists in Canada. The most recent (2019) survey of the Canadian Medical Association identified 2,602 radiologists practising in Canada. A sister specialty, nuclear medicine, uses radioactive tracers emitting gamma radiation to diagnose and treat disease (see Contemporary Medicine). Some radiologists are also certified as nuclear medicine specialists.

Medical Imaging

The second half of the 20th century, with the development of digital electronics and powerful microcomputers, saw the emergence of new ways of looking into the human body using ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission tomography (PET), and fusion technology such as PET/CT. Of these, only CT scanning employs X rays; hence the field of “radiology,” literally the study of rays, is now often referred to as “body imaging” or “medical imaging.” These advances are now an integral part of advanced medical care in Canada.

Legacy

At the dawn of the 21st century, the editors of the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine listed what in their opinion were the greatest achievements in medicine of the previous 1,000 years. Body imaging was eighth on their list of eleven developments. One wonders if Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen, by accounts a modest, introverted man, would have anticipated in 1895 the excitement his discovery was to generate among scientists and laypersons alike, let alone that it would revolutionize the practice of medicine. In recognition of his remarkable finding, Röntgen was awarded the first Nobel Prize for Physics in 1901. (See also Nobel Prizes and Canada.)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom