From 10–27 October 1864, leaders from the five British North American colonies met in Quebec City. They continued to talk about merging into a single country. These talks had begun at the Charlottetown Conference the month before. At Quebec City, the Fathers of Confederation chose how the new Parliament would be structured. They also worked out the division of powers between the federal and provincial governments. The decisions that were made in Charlottetown and Quebec formed 72 resolutions. They were known as the Quebec Resolutions. They formed the basis of Confederation and of Canada’s Constitution.

This article is a plain-language summary of the Quebec Conference, 1864. If you would like to read about this topic in more depth, please see our full-length entry: Quebec Conference, 1864.

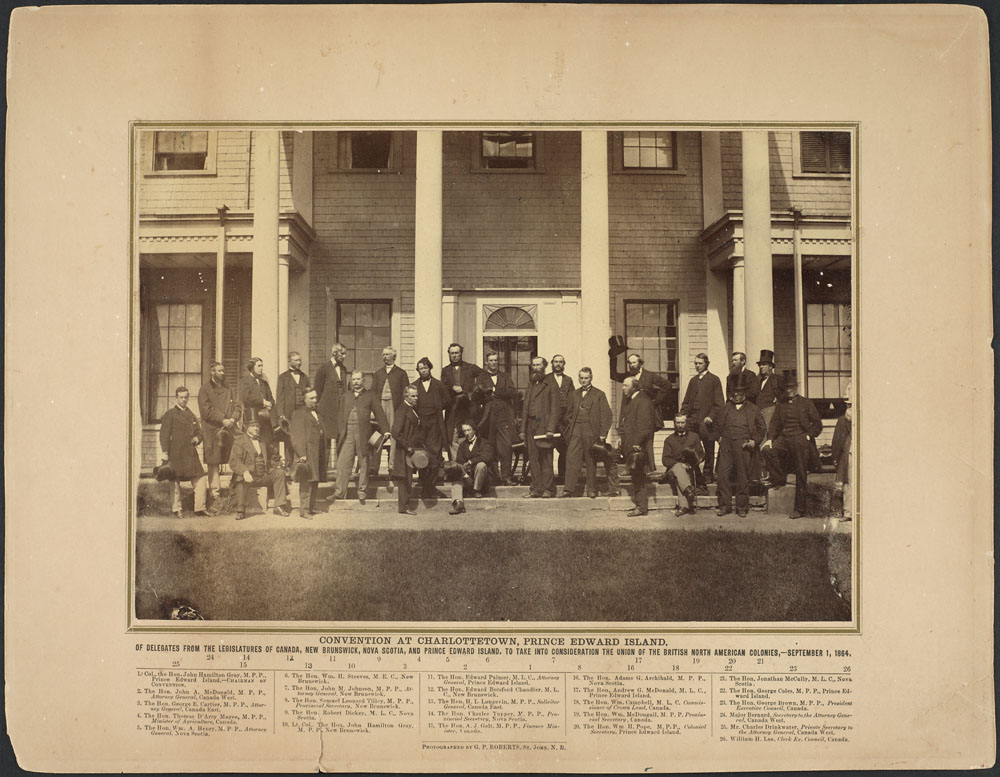

Background: Charlottetown Conference

Britain had five North American colonies: the Province of Canada, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia and Newfoundland. The push to unite them came mainly from Canada West. It was the mostly English-speaking part of the Province of Canada. Politics in Canada West and Canada East had been deadlocked and unstable for years. Conservatives and reformers opposed each other on many issues. Relations between the English in Canada West and the French in Canada East were tense.

Two factors fuelled the desire for strength through unity. One was the fear of being annexed (taken over) by the United States. The other was Britain’s wish to reduce its spending to the colonies. In 1864, of Conservatives and reformers teamed up to form a Great Coalition. They found a way to fix the political logjam. They would unite with the other BNA colonies.

The idea of Confederation had been talked about for years. It was formally discussed for the first time at the Charlottetown Conference. It was held in September 1864. It was held by the three Maritime colonies to discuss their own union. But a group from the Province of Canada came urging Confederation. The idea was agreed to by all.

Quebec Conference

Many of the same delegates who met in Charlottetown met the next month in Quebec City. They are known as the Fathers of Confederation. They met in a grand building near the St. Lawrence River. It is where the Château Frontenac stands today. They talked, debated and socialized from 10–27 October.

Each of the 33 delegates were given sets of cards. They were the size of playing cards. The cards had the names and pictures of every delegate. This way, people knew who was who.

Delegates

Delegates from Canada East included George-Étienne Cartier, Thomas D'Arcy McGee and Étienne-Paschal Taché. Taché was the Province of Canada’s prime minister. He chaired the meetings. George Brown and John A. Macdonald came from Canada West. John Hamilton Gray and Samuel Leonard Tilley were from New Brunswick. Adams George Archibald and Charles Tupper came from Nova Scotia. George Coles and William Henry Pope were from Prince Edward Island. Newfoundland sent Frederic Carter and Ambrose Shea to observe.

Division of Powers

One of the main questions was how powers would be divided. (See Distribution of Powers.) Should the new country have a strong central government? Or should powers be divided between the federal and provincial governments? John A. Macdonald called for a strong central government. He pointed to the breakdown of the US federal system. He saw the American Civil War as a cautionary tale. On the other hand, George-Étienne Cartier worried about francophone interests in Quebec. Maritime leaders feared being dominated by the more populous central Canada. They both wanted a federal system with strong provincial governments.

A balance was reached. Powers would be split between a central Parliament and provincial legislatures. The interests of regions and minorities would be defended. The provinces would have control over education and language, among other things. The federal government’s powers would include control over money, international trade and criminal law. Some areas, such as immigration, would be shared. Both levels of government could raise taxes.

Regional Equality

It was decided that Parliament would have two houses. Members of the lower house, or House of Commons, would be elected. The seats would be based on population. (See Rep by Pop [Plain-Language Summary].) Ontario would have 82 seats. Quebec would have 65 seats. Nova Scotia would have 19. And New Brunswick would have 15. (PEI did not join Confederation until 1873. Newfoundland did not join until 1949.)

Members of the upper house, or Senate, would be appointed. Each region would have an equal number of senate seats. This was meant to protect regional interests. Each of the three regions would have 24 senate seats. The three regions were Ontario, Quebec and the three Maritime provinces.

It was decided that Ottawa would be the nation’s capital. A provision was also made for other regions. They included Newfoundland, British Columbia and the “North-West Territory” (then called Rupert's Land). They could enter Confederation “on equitable terms” at a later time. It was also decided that the Crown would remain the head of state.

Alexander Galt came up with a way to arrange the finances. This generated much debate. A key issue was how the debts of the colonies would be shared. It was agreed that the new federal government would help fund and finish the Intercolonial Railway. It ran from Quebec City to the Maritimes. This was a key condition for the Maritimes’ entry into Confederation.

72 Resolutions

The conference ended on 27 October. The decisions made there formed the 72 Resolutions. Fifty of them were crafted by John A. Macdonald. He was one of the few delegates with legal and constitutional training.

The 72 Resolutions were also called the Quebec Resolutions. They were debated in the various legislatures in the years to come. They went on to form the basis of Canada’s Constitution. In 1866 and 1867, they were turned into a bill at the London Conference. It was the final meeting in the Confederation process. That bill became the British North America Act (now called the Constitution Act, 1867). It created the Dominion of Canada. It was passed by the British Parliament and became law on 1 July 1867. (See Canada Day.)

See also Great Coalition of 1864 (Plain-Language Summary); Charlottetown Conference (Plain-Language Summary); London Conference (Plain-Language Summary); Quebec Resolutions (Plain-Language Summary); Confederation (Plain-Language Summary).

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom

![The province of Canada [cartographic material]](https://d2ttikhf7xbzbs.cloudfront.net/media/media/bf6a8447-8306-4749-bb63-2f6129eb20a6.jpg)