Yucho Chow, photographer (born 3 June 1876 in Kaiping, Guangdong province, China; died 10 November 1949 in Vancouver, BC). Yucho Chow was Vancouver’s first and most prolific photographer of Chinese descent in the early 20th century. Over his 42-year career spanning periods of great upheaval, Chow’s Chinatown photography studio was a momentary refuge for countless families and individuals from marginalized communities. His work provides a diverse tapestry of Vancouver’s past. He photographed people from Black, Chinese, Sikh, Hindu, Indigenous and Eastern European communities. The famous and wealthy turned up in his collection, and so did the poor. If they couldn’t have their photos taken at other studios because of the colour of their skin, they knew Chow would welcome them. (See also Racism.)

1907 Chinatown Riot

Like all immigrants from China, Yucho Chow paid the discriminatory Head Tax to come to Canada in 1902, costing him a hefty $100. Very little is known about his life prior to 1906–07 when his studio opened on 68 West Hastings Street. Family members speculated he might have been a domestic worker. The only clue is a newspaper advertisement providing his service as a Chinese language interpreter.

When Chow arrived and opened his photography business there were deep racial divisions playing out across Canada and the Lower Mainland region in British Columbia. Around the time he opened his studio in Chinatown, anti-Asian racism permeated all aspects of life, including employment, housing, education and civic engagement. From 7 to 9 September 1907, angry white protestors attacked storefronts and businesses in Vancouver's Chinese and Japanese communities. Protestors saw Japanese and Chinese people as threats to their livelihoods. Others felt that their growing populations could destabilize a white majority population. (See Racial Segregation of Asian Canadians.)

Family Stories

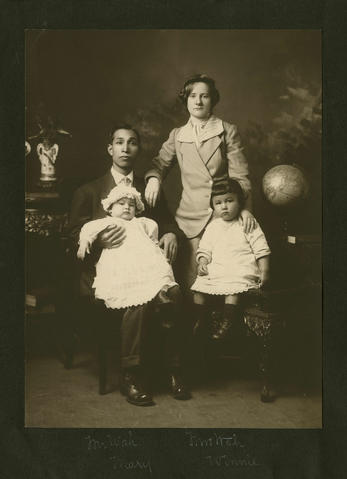

Yucho Chow Studio operated in a climate of racism and discrimination. His photographic portraits captured the stories of the disenfranchised, but they also reflected the hardships of life for early immigrants. Many of his clients were Chinese, South Asian or Eastern European bachelors. Some probably worked on the Canadian Pacific Railway or in Canada’s natural resource industries. Sometimes, Chow helped reunite families through photography. Such was the case with a picture featuring a man with his grown son superimposed with a woman and another child who likely had their picture taken in China. The story reflects Chinese families’ desire to be together ― something potentially impossible because of the Chinese Immigration Act, which prohibited Chinese immigration for 24 years.

Children often appeared in family portraits taken by Chow. In 1940, Chow photographed the Grant family, including their three oldest children: Gordon, Larry and Helen. Their mother, Agnes Grant, was Musqueam (see First Nations in British Columbia), while their father, Hong Tim Hing, was Chinese. The Grant family could not live together because of the Indian Act. Mixed-race marriages were uncommon and frowned upon at the time, but Chow’s collection documented several interracial weddings and families. Families of Italian, Croatian, German, Jewish, Romanian, Japanese, Sikh, Hindu and South Asian heritage also transited through Chow’s studio.

Among photos of children are ones belonging to the influential Louie family (see Brandt Louie). One of them is a portrait of patriarch Hok Yat Louie’s child ― a young boy named Quan J. Louie. Despite not having legal status in Canada, the Canadian-born Quan Louie later enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force and served during the Second World War. Today, the family business, H.Y. Louie Company, is best known for operating London Drugs and IGA supermarkets.

Because Chow’s studio operated through the Great Depression, First World War and Second World War, it captured the portraits of numerous veterans. One of them was Harry Gong. It is believed that Gong was the only Chinese Canadian to have piloted the famous Spitfire fighter plane. (See also Hawker Hurricane.) Chow was the wedding photographer for Harry and Leah Gong in 1948.

Other notable clients included Dr. Sun Yat-Sen, Won Alexander Cumyow, Douglas Jung, an infant Wayson Choy with his adopted parents, and former British Columbia attorney general Wally Oppal.

The Chow Family

During Yucho Chow’s career, his studio occupied four different locations around the Chinatown area. Ultimately, the studio settled in at 518 Main Street from 1930 until his death in 1949. Among the photos he took were pictures of his own children at different stages of their life. The eldest of seven children, a girl named Mabel appeared in numerous photos taken by Chow. Mabel was very much part of running the business. She helped him set up the lights, develop film and hand paint some of the photos ― something that his youngest daughter, Jessie, perfected as well.

When Chow died of a heart attack in 1949, his sons Peter and Philip took over the studio and relocated a few doors down. When his sons retired in 1986, not knowing what to do with the negatives, Chow’s entire collection of negatives was thrown away.

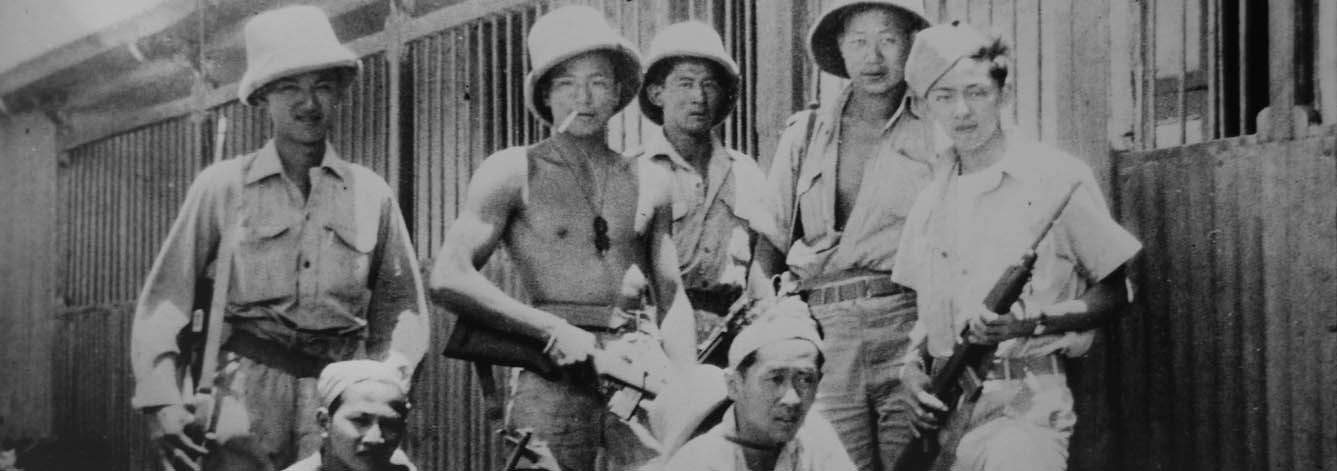

Decades later in 2011, community historian Catherine Clement discovered surviving photographs by Chow. She was working on a project about Chinese Canadian Second World War veterans (see also Chinese Canadians of Force 136) when she started noticing Chow’s signature seal stamped on photos tucked away in family albums. It took her 10 years to recover some of Chow’s lost work. Clement slowly pieced together a collection “one photo at a time, one family at a time, one story at a time” she later wrote.

The project led to a first-ever exhibition and a book titled Chinatown Through a Wide Lens: The Hidden Photographs of Yucho Chow, published in 2019. In it, Clement describes the unexpected discovery of a studio that opened its doors to people of all backgrounds.

“These photos, capturing the passage of everyday people, freezing in place their hopes and aspirations, and marking their victories large and small, are the last visual evidence that this story…their story…ever took place,” Clement wrote in her book.

In 2021, Clement donated over 600 archived photographs from her research to the City of Vancouver Archives.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom