Cet article a été initialement publié dans le magazine Macleans (06/02/1995)

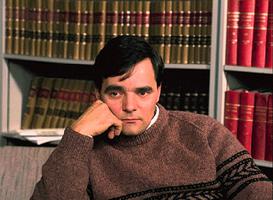

At 35, Guy Paul Morin has already endured far more trauma than most people could expect in a busy lifetime. For 10 years, he was falsely accused of murdering nine-year-old Christine Jessop, put through two lengthy trials, spent 18 months in jail and faced the prospect of spending the better part of his life in a federal penitentiary. But there is little in his relaxed, animated manner that betrays his pain. While others might have become guarded and humorless, Morin has retained a boyish, spontaneous side even as he has grown into a worldly adult. Last week, as he lounged in his lawyer's downtown Toronto office a few days after his exoneration on the basis of new DNA testing, Morin was by turns humorous, matter-of-fact, intense and, briefly, angry. Although he prides himself on how he handled the ordeal, he is under no illusions about its cost. "Knowing that you have always been a joker, and having it plucked away from you at such a critical time in your life - it's really difficult to adjust. But I will get it back. Just give me time, and I will be as good as my old self."

What Morin will never get back, of course, is a decade of normal living. He felt like he was "raped" of life, he says now. He has proclaimed his innocence from the moment he was arrested in spring, 1985, for the Oct. 3, 1984, abduction and murder of his pretty, outgoing young neighbor in Queensville, Ont., 60 km north of Toronto. A lack of anything more than circumstantial evidence, and the jury's acceptance of Morin's alibi, resulted in an acquittal at his first trial in 1986. But in an unusual move, the Crown appealed the verdict. A second, nine-month trial ended in a conviction in 1992, despite evidence of police wrongdoing and controversy about the strategies employed by the Crown. Now, Morin and his lawyers are demanding a public inquiry into the conduct of many of the officials connected with the case. Ontario Attorney General Marion Boyd, however, has delayed making such a decision until she receives a report on whether an inquiry could prejudice the now reopened police investigation into Jessop's murder. "I think there are a lot of people out there who made major mistakes," Morin says. "Were they deliberate? I don't know. There should be an inquiry to determine whether they should be charged."

By the middle of last month, the tide at last began to turn in Morin's favor. That is when he learned that scientists in Boston had, for the first time, succeeded in producing a clear DNA imprint from the semen found on Jessop's underpants. Two other attempts had failed, partly because of the extremely poor condition of the semen on Christine's weathered underwear. This time, however, improved techniques for removing foreign materials helped reveal a clear genetic profile of the killer. All that remained was to obtain an analysis of Morin's genetic pattern from blood voluntarily supplied by him. On the evening of Jan. 19, Morin received a late-night telephone call from one of his lawyers, James Lockyer. Would Morin please come to his home right away? He and his girlfriend, Allison Ferguson, immediately drove from Oshawa, where they were having dinner with friends, to Lockyer's house in the Beaches area of Toronto. "When I arrived, James looked so happy, but I already knew what he was going to tell me," Morin said. "I knew that was not my sample."

The following Monday, prosecuting lawyers moved quickly to end the longest, most controversial murder case in Canadian history. At about 11 a.m. on Jan. 23 - the same day Morin's appeal from his 1992 conviction was to begin - the Ontario Court of Appeal declared Morin a free man. Senior Crown counsel Ken Campbell took the highly unusual step of shaking Morin's hand and expressing "deepest regret" for what had happened to him. As he stood surrounded by reporters and well-wishers outside the courthouse, Morin exuded jubilation and relief. "I've known I was innocent for the past 10 years and finally, DNA has proven it scientifically - thank God."

For the Jessop family, however, Morin's exoneration only brought renewed anguish. Christine's parents, Janet and Robert Jessop (who are now divorced), and brother Ken, then 14, were devastated when her decomposing body was discovered in a wooded property in the municipality of Durham, about 50 km east of the Jessop's home in Queensville. It was Dec. 31, 1984, almost three months since her abduction. An autopsy showed that she probably died of stab wounds and that she may have been raped before her death. Throughout the investigation and trial of Morin, the Jessops frequently reiterated their conviction that he was guilty. Even last week, Robert Jessop asked Boyd to delay compensating Morin until police complete a thorough reinvestigation. "I told her everything else in this case has been almost choreographed to go wrong in the last 10 years," said Christine's father. "This could be another." But Ken Jessop told Maclean's: "A sadistic, dangerous person is still out there. Attention should now be turned to the search for Christine's killer," her brother said, adding that he is in favor of a public inquiry. "The Morins need to know. I personally need to know. I feel like I've been lied to for 10 years."

The case was difficult from the beginning. In the weeks following the discovery of Christine's body, the police unearthed several strong suspects but no direct evidence linking any of them to the crime. Soon, however, they began to focus on Morin, apparently because of what they viewed as his strange behavior. Morin, who lived next door to the Jessops with his parents, Ida and Alphonse, played the clarinet in a local band, kept bees and did home renovations. The police were made suspicious by such things as Morin's failure to attend Christine's funeral - he later testified he had never been to a funeral and thought he had to be invited. One officer wrote in his notebook that Morin was a "weird-type guy."

As the proceedings wound through the courts, the case against Morin grew into a tangled web of circumstantial evidence that was plagued by errors and tainted testimony. Four months after Christine was buried, the Jessop family discovered more of her bones at the site where she was found. Her body was exhumed and another autopsy performed, showing that several significant injuries had been missed. Five microscopic fibres found in Morin's car were similar to those in Jessop's clothing, but the source of the fibres could not be determined by forensic experts. A British fibre expert, who completed a report that was heavily relied upon by the Crown, stated in a September affidavit that his analysis had been grossly misunderstood. And last summer, Robert Dean May, one of two former inmates who testified that Morin confessed to the murder while in jail, told three of his friends, and his parents, that he had lied.

By the end of the second trial, there was already a groundswell of public support for Morin. A 1992 book written by journalist Kirk Makin, Redrum the Innocent, outlined the flaws in the Crown's case in stunning detail. In February, 1993, Morin was granted bail, partly because of the widespread support for his cause. Even Christine's father, Robert, had come to doubt the integrity of the process. Jessop says that he still feels frustrated by the way the case was handled. "I know the police made mistakes, and the police know they made mistakes," he says. "It's almost like a script for the Keystone Kops."

Almost from the beginning, however, Morin himself has pressed for DNA testing to prove his innocence. Prior to the first trial, Morin's counsel, Clayton Ruby, advised him that DNA analysis was in its infancy; it would be more prudent, he argued, to wait for better technology rather than destroy any of the already deteriorated semen sample in a test that was likely to prove fruitless. And in fact, two later attempts, in 1989 and 1991, did fail. But by last year, techniques for isolating DNA from small and contaminated samples had improved considerably. According to prosecutor Ken Campbell, that prompted the Crown to apply on Sept. 1 for another series of tests. "We came to believe there would be a scientific answer and that it would be best for everyone, no matter what the result was," he said.

This time, a week of preliminary work showed that the chances of obtaining a clear result were good, and on Jan. 19, the defence agreed to using more of the remaining sample. At 6 p.m. the scientists called: they had obtained a DNA imprint from the semen. Could they now proceed to test Morin's blood sample? Morin recalls his lawyers asking him: "Are you sure, for the final time, are you sure?" He was sure. "It was Jack Pinkofsky," he says now, "who said, 'That's it, he's free, it'll be all over soon.'"

For Morin, however, there is still much to be resolved. He is eager to catch up with all the things he has not been able to do - travel, buy a house, work full time at renovating houses. "The justice system has acted in a criminal way," he says, when he thinks of what has been taken from him. For the most part, though, Morin is upbeat. He says it was partly his own resolve and partly the support from family and friends that helped him through the past 10 years. His younger sister, Lisette, the last of six children, says that "when Paul went to jail, we all went with him. We were no better off, even though we were on the outside." It was also watching what prison can do to people, Morin says, that kept him from sliding into an emotional black hole. "They have so much anger, so much bitterness - they are consumed." He owes an enormous debt, he acknowledges, to science. "We all have our own genetic pattern and isn't that wonderful," Morin says. "And it is wonderful for you as much as it is for me. Because what happened to me could happen to you. And I have been through an experience that I would not wish on anyone."

Maclean's February 6, 1995

Partager sur Facebook

Partager sur Facebook Partager sur X

Partager sur X Partager par Email

Partager par Email Partager sur Google Classroom

Partager sur Google Classroom