This content is from a series created in partnership with Museum Services of the City of Toronto and Heritage Toronto. We gratefully acknowledge funding from the Ontario Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Sport, and the Department of Canadian Heritage.

Toronto Feature: Discovery of Insulin

"Banting's and Best's Miraculous Cure"

Frederick Banting was an inexperienced medical researcher--a doctor in private practice who moonlighted as a university lecturer to make ends meet. But in a moment of inspiration, he devised an idea for an injectable treatment for diabetes. And, in the spring of 1921, the London-based doctor convinced the head of the University of Toronto's medical school, John Macleod, to take a chance and support his experiments. Charles Best, who'd just received his undergraduate degree in biochemistry, was assigned as assistant.

Working tirelessly around the clock and cooking meals on Bunsen burners, Banting and Best conducted experiment after experiment until one of their canine subjects, Dog 410, responded positively on 30 July. But Macleod demanded further tests to confirm that Banting and Best's injections of pancreatic extract lowered blood sugar, straining his already troubled relationship with the temperamental Banting.

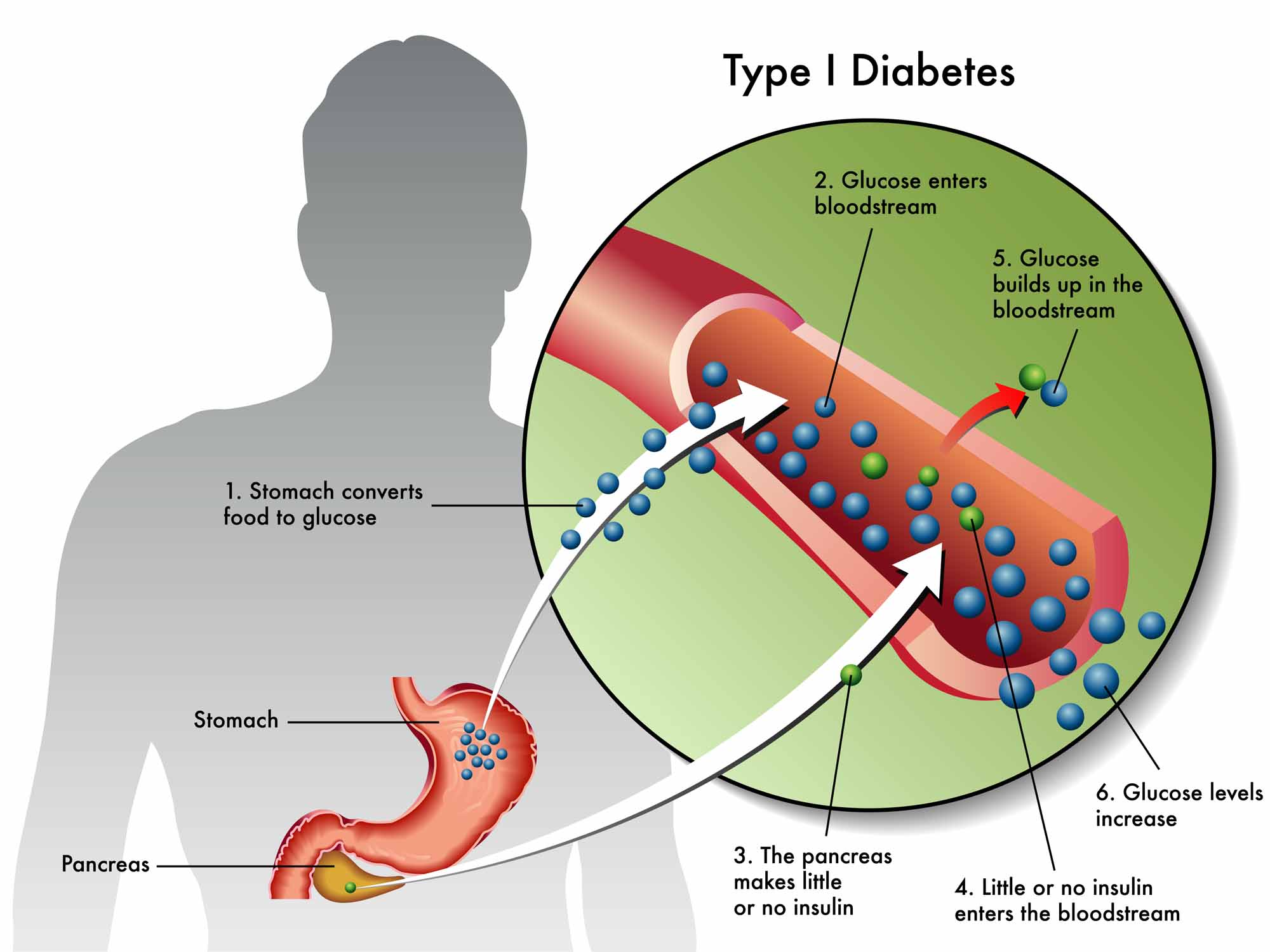

Finally, in January 1922, the first human trial occurred. Leonard Thompson, a 13-year-old charity patient at Toronto General Hospital, was emaciated and lingering near death. Given insulin treatment, within days he was reinvigorated and restored to full health. The recovery of Thompson and other early recipients of insulin made headlines around the world, drawing countless diabetics to Toronto to undergo Banting and Best's miraculous treatment. Insulin is not a cure for diabetes; it is a treatment important in control of the disease.

Where diabetes once spelled his certain death, Thompson would live another 13 years on the strength of regular insulin treatment before succumbing to tuberculosis. His pancreas, removed by autopsy, is now preserved in the specimen collection of the University of Toronto's Pathology Department.

Partager sur Facebook

Partager sur Facebook Partager sur X

Partager sur X Partager par Email

Partager par Email Partager sur Google Classroom

Partager sur Google Classroom